The release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on the impact of human-induced climate change detailed, in no uncertain terms, the scale of the disaster humanity is now facing, with the UN Secretary-General calling it a “code red” for human civilization. Devastating wildfires — like those experienced this summer in southern Europe, in Siberia and in the American west — extreme drought and flood conditions, and so many more horrors are all likely to become norms rather than once-in-a-century or once-in-a-millennia events.

Over the past few weeks, the climate news has gotten worse. Heat domes over the northwest U.S. and the western provinces of Canada killed hundreds of people, devastated wildlife populations on land and in sea, and created desert-like thermometer readings in regions more used to temperate rains and snows. In California, the Dixie Fire is now the state’s second-largest in history. Pollution from western fires is now making the air quality in locales such as Salt Lake City and Denver more dangerous to breathe than the air in New Delhi, which, in recent years, has regularly posted some of the worst air quality data on Earth. Another report suggested the Gulf Stream had now become unstable, and that its breakdown could lead to unprecedented climatic changes in the northern hemisphere. And news stories abounded of the Arctic polar air clogged with smoke from Siberia’s burning tundra.

In the United States, while President Joe Biden and his climate envoy John Kerry responded to the IPCC report by urging immediate action on climate change legislation — and climate activists insisted we must go above and beyond the Biden administration’s demands — Republican leadership, long skeptical of the science of global warming and loath to commit politically to the societal changes needed to get a handle on the cascading crisis, was largely silent in the face of this drumbeat of bad news.

That telling silence from GOP grandees was, perhaps, marginally better than the party’s response to an IPCC report in 2018 that detailed the differences between limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees as opposed to letting things rip and accepting two degrees or more of temperature increases. Back then, under President Trump, the party attempted to dismiss climate change as a hoax, and mitigation strategies as being too much of a drag on the economy. But, in a closely divided Congress, today’s GOP silence is almost as destructive as GOP climate change denialism, making it desperately difficult to pass legislation vital to helping the world to transition away from carbon-based economies. Moreover, even if Mitch McConnell and Kevin McCarthy are staying silent on the IPCC report — and even if senators such as Marco Rubio now begrudgingly and belatedly accept that at least some of the causes of global warming involve human activity — a significant wing of the party, revolving around conspiracists such as Marjorie Taylor Greene, and far right senators such as Ted Cruz, is still firmly wedded to denialism.

Should the Republicans reclaim Congress in 2022 or the presidency in 2024, it’s a fair bet that they would, in short order, reinstate Trump’s anti-environmental policies, and once more put the pedal to the metal on approving new oil drilling leases and weakening fuel economy standards.

In Europe, by contrast, politicians from around the political spectrum have moved to accept the IPCC’s findings and, to varying degrees, take urgent action on climate.

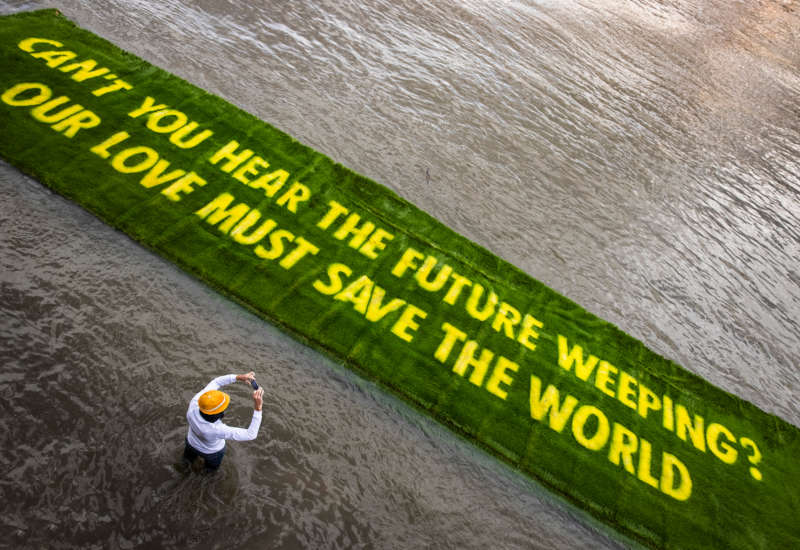

Perhaps nowhere is that contrast between U.S. and European conservatives more in evidence than in the U.K., which is hosting the COP26 summit in Glasgow later this year, where nations large and small hope to hash out specific carbon-reduction goals and international investments to mitigate climate change, and whose government has committed, even if it is hazy on the details, to a carbon net-zero society by the year 2050.

Alok Sharma, the U.K. government’s climate change envoy and the minister in charge of the COP26 summit talks, has repeatedly referred to an imminent “catastrophe” if radical policies to curb the climate crisis are not enacted globally. He has said that large-scale actions need to be implemented now, rather than years down the line, and has averred that wealthy nations are morally obligated to help poorer countries, on the climate frontlines, to put in place costly mitigation strategies.

And, in the wake of the IPCC report’s release, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who has already committed the U.K. to phasing out petrol- and diesel-based internal combustion engines in new vehicles by 2030, said the world must “consign coal to history.”

There are, of course, fierce policy debates in the U.K. as to whether the government is doing enough. Johnson’s conservative government has, quite rightly, come under heavy criticism for paying lip service to climate change goals while, at the same time, giving the green light to more oil exploration in the North Sea, and pondering in recent months whether to open new coal mines in England’s northeast, despite the acknowledgement that coal use is environmentally untenable.

It has been praised for announcing the phase-out of the internal combustion engine in cars, while being critiqued for not having a strategy in place, as France now has, to reduce short-distance flights and replace them with less environmentally destructive train travel. And, internally, the Johnson government is deeply divided over whether or not to impose new import taxes on products that come from overseas with a high carbon footprint. Johnson himself is thought to favor such a tax, but fiscal conservatives in the Treasury have come out in opposition to the idea. So far, it looks as if the Treasury is poised to win that fight.

On other themes dear to conservatives’ hearts, such as hostility to immigration, crafting tax policies that favor the rich and the powerful, eviscerating workplace safety regulations and proving their “tough on crime” credentials, right-wingers in Europe and the U.S. are often in lockstep. On the environment, however, and especially on climate policy, U.S. conservatives are a particularly destructive, and irrational, outlier (although we must also acknowledge that climate policy and economic policy are strongly linked).

The fact that the U.K.’s conservative right-wing government is immersed in an internal policy debate not on whether climate change is a reality, but on how best to use government powers to tackle it, shows how much of an outlier U.S. conservatives have become on this issue — and, given the power they wield in Congress and at a state level, how dangerous their views on the environment are to the future well-being of the world.