We must not allow the tragedy unfolding in Afghanistan to be used to rewrite history and teach the wrong lessons.

The rapid fall of the U.S.-backed government in Afghanistan and the takeover of that country by Taliban extremists has stunned the world. President Joe Biden has nevertheless defended his decision to withdraw U.S. forces, arguing that Americans should not be forced to fight and die for a government when Afghans were themselves unwilling to do so.

Yes, the Biden administration grossly miscalculated how quickly Afghanistan would fall to the Taliban and there should be a thorough investigation. And there should have been broad, concrete plans to open the U.S. to Afghan refugees, as Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Barbara Lee are now proposing. However, Biden was still correct to follow through with Donald Trump’s agreement to withdraw U.S. forces, which polls show had the support of nearly three-quarters of the American public.

We must not erase the U.S.’s longtime role in the creation of the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan: The current chaos and violence have been nearly 20 years in the making. Indeed, Biden actually delayed the withdrawal for several months beyond Trump’s May deadline, making claims by the former president and his supporters that Biden had suddenly decided to “surrender” to the Taliban particularly absurd.

Gerald Ford is generally not blamed for the Communist victory in Vietnam simply because he was president at the time the U.S.-backed regime in Saigon finally collapsed. Similarly, Biden should not be primarily blamed for the Taliban victory in Afghanistan.

The Afghan army officially had 300,000 troops, four times the number of Taliban soldiers. In addition, they had an air force, heavy weapons and had received hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of training, weaponry and equipment from the world’s military superpower. By contrast, the Taliban had no significant foreign backing, no air force, and only light weaponry they had captured or otherwise managed to procure through underground means. Similarly, since there were only 2,500 U.S. troops in Afghanistan for most of the past year, their withdrawal should not have made much of a difference in terms of the strategic balance.

Militarily speaking, there was no reason for the Afghan government to lose and little more the United States could do. This was not, therefore, a military victory by the Taliban. It was the political collapse of the U.S.-backed regime. It is hard to imagine that, after nearly 20 years of U.S. support, had Biden decided to send more arms, more money or more troops, it would have led to a different outcome.

University of Michigan professor Juan Cole, one of the more prescient observers of U.S. policy in the Middle East and South Asia in recent decades, described the U.S.’s policy in Afghanistan as essentially a Ponzi scheme based on an unsustainable system utterly dependent on foreign support in which an eventual collapse was inevitable.

While Biden was correct to point out the corruption and ineptitude of the Afghan government, he unfortunately failed to acknowledge how the United States was largely responsible for setting up and maintaining that decrepit system. And the costs were huge: over $1 trillion, and the deaths of 47,000 civilians, 2,500 American soldiers, 1,000 NATO soldiers, 4,000 civilian contractors, and 70,000 Afghan soldiers and police.

It would be ironic if a narrative takes hold that Biden is not militaristic enough — given his strident support for the invasion of Iraq, his defense of Israel’s recent war on Gaza, his insistence on maintaining an obscenely bloated military budget, his backing of allied military dictatorships, his providing jet fighters to those responsible for the terror bombing of Yemen, and other policies.

There are certainly areas regarding Afghanistan policy for which Biden should be criticized, such as the failure to adequately prepare for such a quick collapse of the regime in terms of evacuating Afghan translators, government officials, human rights activists, and others now at serious personal risks under Taliban rule. In addition, he should have never supported the September 2001 war authorization which went well beyond targeting Al-Qaeda and left the door open for decades of open-ended conflict in Afghanistan. On that war resolution, of course, he was certainly not alone: only one (Rep. Barbara Lee) of the 535 members of Congress voted against that resolution, despite people like me warning at that time that sending U.S. ground forces into Afghanistan would result in “an unwinnable counterinsurgency war in a hostile terrain against a people with a long history of resisting outsiders.”

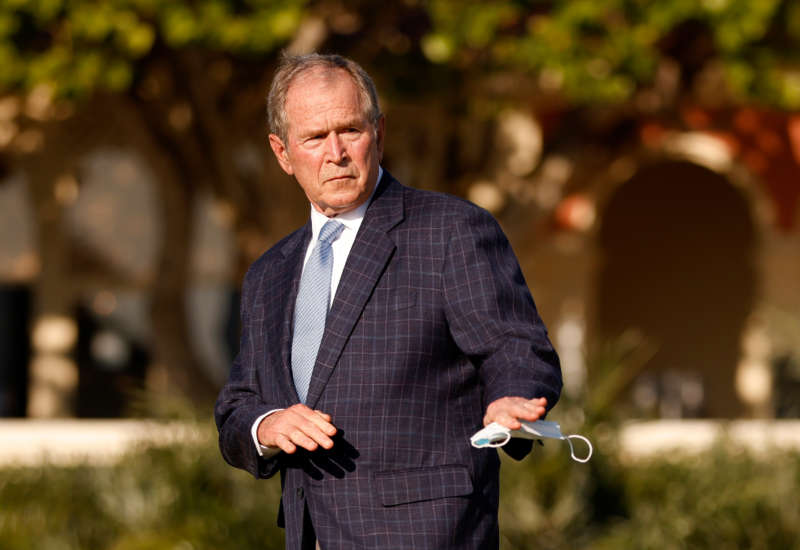

Even more problematic was Biden’s key role in pushing the 2002 Iraq War Authorization through the Democratic-controlled Senate, which — unlike the authorization for the war in Afghanistan — was opposed by the majority of congressional Democrats. The Taliban had essentially been defeated by that time. However, the George W. Bush administration, supported by then-Senator Biden and some others, decided not to finish the job but to instead put the focus of our troops, our generals, our intelligence, our satellites, our money, and pretty much everything else on invading and occupying Iraq. It was during the years of counterinsurgency war in Iraq that the Taliban made their comeback, crossing back over from Pakistan to reconsolidate their control in rural Afghanistan and begin their gradual takeover of the country, culminating in their recent takeover. If the Bush administration and its congressional allies like Biden hadn’t insisted on invading Iraq, the Taliban might have remained a small exile group in the Pakistani tribal lands.

The Washington Post has published a series of articles on how, particularly under President Bush, the U.S. government systematically lied to the American people about the supposed progress being made in the Afghan War. Despite claims of strategic gains by U.S. and Afghan government forces, the heavy bombing of the countryside, the search-and-destroy operations, the raids on villages, and the tolerance for rampant corruption ended up alienating much of the Afghan population from the United States and its allies in Kabul. Much of the Taliban’s support over the past decade has come not from the small minority of Afghans who embrace their reactionary misogynist ideology, but those who saw them as the vanguard of resistance against foreign occupiers and their corrupt puppet government. The United States allied with warlords, opium magnates, ethnic militias, and other unrepresentative leaders simply due to their opposition to the Taliban and with little input from ordinary Afghans themselves.

In my nearly 20 years of working with Afghans and Afghan Americans, including those from prominent political families, my strong sense is that most them supported an active and ongoing U.S. role in Afghanistan in principle, but believed that it should have been about 10 percent military and 90 percent focused on grassroots political and sustainable economic development, especially empowering civil society. Instead, U.S. funding and the overall focus of U.S. officials was 90 percent military, and much of the development work consisted of top-down projects of dubious merit through corrupt elites.

And no analysis of the Afghan tragedy would be complete without observing how the United States played a critical role in the emergence of the Taliban in the first place: In the 1980s, the Reagan administration was less interested in liberating the Afghan people from the Soviet-backed Communist dictatorship than it was in prolonging a counterinsurgency war that would weaken the United States’s superpower rival. They figured that the most hardline elements of the anti-Communist resistance were less likely to reach a negotiated settlement. Of the six major mujahideen groups fighting the Afghan government and its Soviet allies, 80 percent of U.S. money and arms went to Hesb-i-Islami, led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who subsequently became a close Taliban ally. For similar reasons, the United States and its Saudi allies promoted religious studies along extremist and militaristic lines among Afghan refugees in Pakistan, out of which emerged the Taliban — the Pashtun word for “students” — in the 1990s.

There is plenty of blame to go around for the tragic turn of events in Afghanistan. It should not, however, be focused on Biden’s reasonable refusal to break off the withdrawal agreement of his predecessor, which would have inevitably led to the resumption of never-ending combat operations by U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

As reports of Taliban atrocities come out in the coming weeks, months and years, we must not allow the advance of a narrative which argues that the U.S. war in Afghanistan should have been bigger and longer or that Biden is inadequately supportive of U.S. military intervention overseas. While we should certainly hold Biden accountable for his role in initiating and fueling this war, it’s also important to refute spurious accusations from the right, which could lead future presidents to needlessly prolong unwinnable wars.