Diversion programs are presented as exit ramps to incarceration, offering alternatives to life behind bars and providing resources to individuals who would have otherwise been arrested and sentenced to prison.

When an individual commits a crime, they are arrested as an entry point into the criminal legal system and transitioned through a traditional court trial and sentencing. Through diversion, individuals avoid this process altogether or partially by instead receiving treatment or rehabilitation programming designed to address what led them to commit the crime. But what happens when those diversion programs intended to help end up doing more harm than good?

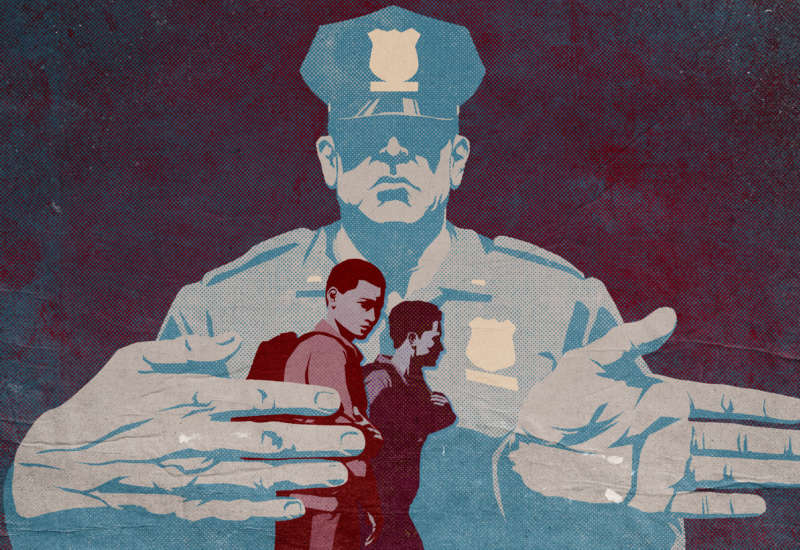

The Prison Policy Initiative, a research and advocacy nonprofit organization that exposes the broader harms of mass criminalization, brings this question to the forefront, informing us that not all diversion programs are created equal. For Black and Brown youth who face the brunt of arrests, incarceration and criminalization, diversion programs can be good, but not when they center the institution of policing to carry them out.

An example of this is Philadelphia’s police school diversion program, piloted in 2014 to combat the rise of youth arrests in schools and provide them with community-based resources. The program, in partnership between the Philadelphia Police Department and the School District of Philadelphia, at first appears to be a successful program. The Philadelphia Inquirer boasted that the program was a “promising reform,” and that its founder, former Philadelphia Deputy Police Commissioner Kevin Bethel, “broke the school-to-prison pipeline.” After all, the program decreased youth arrests across the school district in a moment where youth arrests and incarceration rates have fallen throughout the U.S.

Entry into the program begins when a school-based incident occurs. The school has a choice to then make an independent disciplinary decision but will generally inform the school safety office or a Philadelphia police officer. The officer assesses whether that child can or should be diverted. If the child has no prior school record and the officer deems the crime to be “low-risk” or “non-serious,” they may offer diversion. Otherwise, they are arrested.

For youths who are diverted from arrest, they are visited by a social worker and followed up with voluntary community-based services such as mentoring, academic support or victim-offender conferencing. Throughout this process, diverted youth and the services recommended to them are tracked and documented by the Philadelphia Police Department, widening the scope of information these officers have of the youths.

While this appears to be an effective and promising reform, its involvement with police draws major concerns which have been voiced by the community. For instance, one Philadelphia student, Alison Fortenberry, voiced that these police officers view her and other youths not as students, but as criminals, thus purporting the narrative of criminality. Alison is not alone here. Her concern joins the chorus of several other students organizing within the Philly Student Union, a youth-centered organization focused on demanding high quality education, who have been pushing for schools to disband police entirely.

The reality of this program is that it is predicated on the notion that police can be repackaged with a “softer” approach to school safety. It relies on rebranding Philadelphia police as “safety officers” who opt to wear more casual clothes with no badge, but as we should expect, still police. It negates the important details that police are traumatic, and increases the likelihood that Black and Brown youth are criminalized.

By strengthening police power … reformers for police-led youth diversion programs inevitably build capacity for the prison-industrial complex.

Sure, fewer youths are arrested and more are provided with community-based services through the program, but the stigma of criminalization that follows them and the strengthening of the prison-industrial complex does not go away — police reinforce that. It goes away by removing police from the equation altogether.

We cannot allow ourselves to be duped by police-led youth diversion programs, believing their effectiveness on the premise of being reforms to combat youth arrests and incarceration. These reforms inevitably fall short for real long-term change and further construct an illusion that police should be present in our everyday lives, such as the schools youths occupy. Even if these are what appear to be promising efforts of diversionary reform, policing has one goal: to police.

To understand why police-led youth diversion programs should be avoided, we must turn to policing and its impact inside the schoolhouse gate.

Firstly, there are a few things to know about police: They lie; incite racist, sexist, transphobic, heterosexist and ableist violence and harm; and often make situations much worse. The institution of policing and police themselves are inherently violent and racist entities — history informs us of that. But how has this taken shape in schools?

Think about some of the headlines that have taken space on the news and newspapers recently, sparking debates in the U.S. about police overreach and the harm caused by them in schools. From 17-year-old Anthony Thompson Jr., who was shot and killed by police inside a school bathroom stall, to a 4-year-old girl in Virginia with ADHD who allegedly threw a block at another student and was later handcuffed, transported to a squad car and taken to the sheriff’s office, police officers have had a substantial role in school violence and punishment towards youths.

These are but a couple of many examples occurring against the backdrop of how police presence in schools has changed the educational landscape for the worse. Instead of protecting youth, police in schools appear more often to be guarding the school like a prison. Entrances to the school that were once welcoming and inviting instead have metal detectors and are monitored by stationed patrol cars.

Taken altogether, police presence in schools does not make the experiences of youths better and leads to worse outcomes for them, particularly Black and Brown youth.

What does this mean for police-led youth diversion programs? On the surface, they may appear to be a strategy to combat youth arrests and incarceration. However, the effect of keeping police in schools and positioning them to lead diversionary programs is that they have exacerbated the violence of policing and harm against marginalized communities. Moreover, police-led youth diversion programs do not help combat the prison-industrial complex.

Police-led youth diversion programs strengthen the building of carceral capacity — what political scientist Heather Schoenfeld describes as the dramatic increase in the state capacity to punish through new bureaucratic structures, new frontline and administrative positions, new staff training and new protocols across the criminal legal system.

By strengthening police power — allowing them to be the first responders to school incidents and determining who is diverted — reformers for police-led youth diversion programs inevitably build capacity for the prison-industrial complex.

Supporters of these diversion programs might argue that things have gotten better while working to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline. Children get to stay in school and they avoiding an arrest and incarceration. But given what we know about the impact of policing and police presence in schools, do these programs constitute progress?

Progress is recognizing the harm that police have done throughout history. It is making a conscious choice to position other entities, such as counselors in youth diversionary reform. It is also making a proactive shift to providing communities with what they need — housing, health care, quality education — so instances that would have otherwise involved police are not needed.

Maya Schenwar and Victoria Law remind us that innovation in itself is no guarantee of progress. If we are to consider how we make progress in ending mass incarceration among youth and adults, we must critically think about how we stop creating new diversionary policies out of mechanisms of the prison-industrial complex.

While the focus here has been on police-led youth diversion programs, in any measure of reform — be it youth-diversion reform or reform to combat drug addiction among adults — we must ask ourselves whether the proposed diversion program will divest power from carceral institutions. Ask yourself if the diversion program is aligned with doing away with carceral capacity rather than expanding it. A police-led diversion program, be it for youth or adults, is not the answer.

We cannot settle for simply the appearance of slight improvements, some of which may actually expand the realm of policing and the prison-industrial complex. Instead, we must aim for progress — for fundamental transformation.