My first class for the Spring semester begins in a couple of hours. I still do not know if I’m teaching in person or moving the class online. Governor DeSantis says I’m teaching in person. The university, where I work, says I’m teaching in person.

“I have tenure. Why the hell am I teaching in person?” I ask my partner.

“I don’t know,” he says.

“Do you think I’m going to die?” I ask.

“Good news: we’re all going to die,” he says, and this makes me laugh in a macabre way. We’re both poets. He teaches at Harvard and flies back in a couple of weeks.

I walk into my home office and play music. The playlist I want is bizarre, but at least I’m clear on what I want to listen to: Aphex Twin’s “Alberto Basalm,” Tristen’s “Baby Drugs,” Schubert’s “Trio No. 2” and Hole’s “Malibu.”

I apply makeup and think: What would Courtney Love do? Courtney Love is disabled. What if Courtney Love were a poetry professor about to teach in person?

She’d cancel, I decide. She would definitely cancel.

I change my mind. No, she would mask up, walk in the classroom and say, “Well, here we are.”

***

In Fall 2021, I did not deliberate as much about teaching in person. I just did it.

I had applied for this job as a creative writing professor at Florida State University (FSU) three times. Twice, I had been rejected. When the job ad appeared, yet again, I nearly did not apply.

“Why give them the chance to reject me again?” I asked my partner.

“The search committee changes,” he said.

So I applied a third time. And landed the job.

I was thrilled. I returned to teach at my alma mater. As an undergraduate, I had appreciated neither the education at FSU nor the 14 practicing writers on faculty. I was just an in-state student who could not afford out-of-state schools.

***

I’m a disability rights activist, so I know how much it means when allies show up. And I know how much it hurts when allies don’t show up.

On the road to teach in person, I call my colleague, the novelist Mark Winegardner, and say, “Mark. What are we doing? Talk to me like I’m your high-risk disabled friend. And I’m about to teach in person.”

“You’re vaxxed, right?” Mark says.

“I’m vaxxed and boosted and I’d take a fourth hit if they’d give it to me,” I say.

“I think you’ll be fine. But don’t take my word for it. Do what you think is right,” he says.

“I just passed a COVID testing site. The line of cars is out of this world,” I say.

***

In the Fall, I felt a sense of camaraderie about teaching in person.

I’m tenured, I thought. What can I do with my tenure? Okay, I’m not going to sit at home and luxuriate. I’m not going to teach online because I have job security. Not while adjuncts and grad students and staff have to be there, in person, on the job.

I’m a disability rights activist, so I know how much it means when allies show up. And I know how much it hurts when allies don’t show up.

But I’m no martyr, no moral authority. I cuss like a sailor. I have been a coward on more occasions than I’ve been a hero.

In the Fall, this felt like an adventure. Recklessly going into the unknown.

***

But now here we are. Omicron is blowing up. What are the risks?

***

It probably helps if you know that I was born disabled due to Agent Orange. My dad was drafted into Vietnam in the 70s (“what a stupid war,” he has said), and he served as a pharmacist in Long Bình. He sat on a barrel and he dispensed pills.

That barrel he sat on? It contained Agent Orange. Then again, so did the fields around him. Did I get my disability from the barrel or the fields? Does it matter?

My parents, reformed hippies, wanted me to have all the information. So even though I was a kid, I learned about the potential for my own death. Each surgery came with a new talk about “the risks.”

“Do you understand the risks?” my parents would say.

***

Am I teaching in person? What are the risks? Not just for me, but for my students. Where is the uprising of professors? Where is the change.org petition?

Percy Shelley, of all people, keeps popping into my mind: “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

If that’s true, then I am the legislator. I am the keeper of attendance.

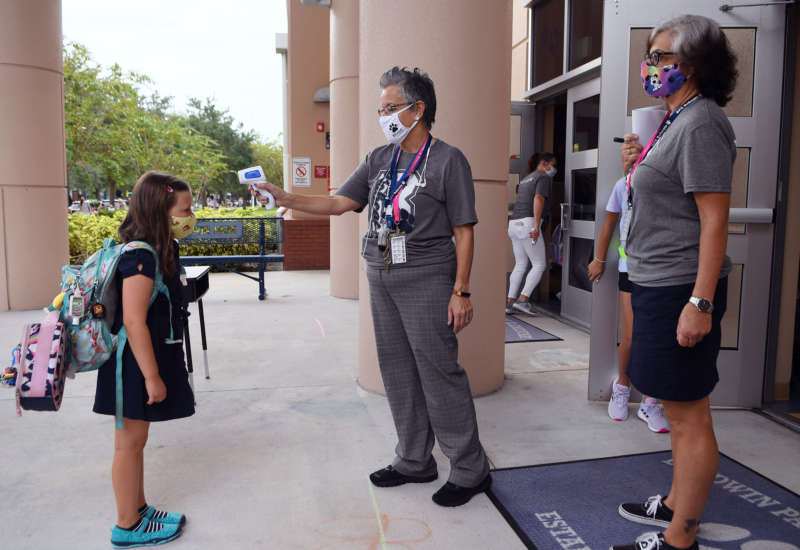

I could turn this car around. I could send one email: “We’re going online.” I could disobey my superiors and the State. But I don’t. I go in there, double-masked, and say to my students, “Welcome to class.”

***

To my critics, who wonder, “Why don’t you just get an accommodation?”

Have you applied for one? Would you risk additional exposure to visit your doctor’s office for his or her signature on the paperwork? Would you risk possible re-traumatization since your university wants your complete medical history from 1981? Would you be fine with all of this even if your university decides to decline your request? Or would you wish that you had never asked?

If you never ask, then you are never denied.

If you are never denied, then there is no record.

If there is no record, you can take your classes online. Wait to be reprimanded. Reply, “I didn’t know what to do. I was afraid of dying.”

***

Though I may feel alone, I am not alone. Mia Mingus has just published “You Are Not Entitled to Our Deaths” on her blog. One part of the essay reads, “We know the state has failed us. We are currently witnessing the pandemic state-sanctioned violence of murder, eugenics, abuse and bone-chilling neglect in the face of mass suffering, illness and death.”

I do not have answers.

I am walking into class, again, in 20 minutes. Dramatic Technique.

Today we will talk about Sarah Kane’s play Crave. Kane was a queer, disabled playwright. Here is one of the lines from her play that I’d really like to believe: “You’re never as powerful as when you know you’re powerless.” Another line? “I have a bad bad feeling about this bad bad feeling.”