On January 21, a coalition of forces led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) carried out an airstrike in Yemen that is now confirmed to have killed at least 87 people. As many as 266 were also wounded in the strike, which targeted a detention center in the northern city of Sa’ada that reportedly housed African migrants. Fragments of the bombs bore a unique manufacturing code for Raytheon, one of the largest U.S. weapons contractors. On the same day, the coalition bombed a telecommunications building in Hodeidah, a crucial port city that has been the site of several major battles over the course of the conflict. That strike caused a nationwide internet outage that lasted for days, resulting in delays to the limited humanitarian relief that’s allowed into the country.

“I’m still trying to process that 24 hours ago, Saudi Arabia, the United States, and the United Arab Emirates disabled an entire country’s internet service while committing various massacres around Yemen and this isn’t top news everywhere,” tweeted Shireen Al-Adeimi, an assistant professor at Michigan State who was born in Yemen.

The strike on the prison was one of the deadliest in recent years, but is largely in keeping with the Saudi-UAE coalition’s tactics since the beginning of the war, which will soon enter its eighth year. The conflict has resulted in famine, sickness and instability throughout the poorest country in the Middle East, if not the entire world. The recent strike on the prison was preceded by a Houthi attack on Abu Dhabi, the capital of UAE. Three people were killed and six were wounded in those attacks. The Houthis have controlled the capital, Sana’a, since 2014, and are opposed by Saudi Arabia and UAE. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken condemned the Houthi attacks in a statement, but declined to comment to The New York Times when asked about the deadly strike on the detention center.

The war is almost entirely absent from U.S. mainstream media headlines, despite the U.S.’s evolving role in the conflict since its inception, and its increasingly direct involvement in hostilities. On Monday, the U.S. Air Force intervened to stop a Houthi air attack on UAE, the second in a week. Houthi forces have regularly attacked Saudi targets over the course of the war, but they typically haven’t struck inside UAE until recently.

The war in Yemen is often described in U.S. media as a proxy war of sorts between Saudi Arabia and UAE on one side and Iran on the other, in the form of the Houthi movement. While it is true that the Houthis receive support from Iran, their movement began in northern Yemen in part as a response to corruption and heavy-handed governing by then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh. He was swept out of power in 2012, during the Arab Revolutions, and succeeded by the hapless Vice President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi. In 2014, the Houthis took control of the capital, Sana’a, and Hadi fled the country the following year, which was also when Saudi Arabia and the UAE began their bombing campaigns. Since then, Hadi has been the internationally recognized president, though within Yemen and the broader region, he is largely seen as controlled by Saudi Arabia.

In addition to these forces, there is another player in the conflict: southern separatists who initially wanted to reestablish the south as its own state, as it was prior to unification in 1990. They rescinded that demand as part of peace negotiations in 2020, but the power-sharing framework known as the Riyadh Agreement hasn’t been fully implemented. The UAE has supported the southern movement to shore up its own access to the area’s natural resources and ports, which has caused tensions with Saudi Arabia, which sees southern independence as a challenge to Hadi and what’s referred to as the legitimate government.

This multifaceted war between local movements and their international sponsors, very much including the United States, remains one of the most intractable conflicts in the world. “Ensuring peace in Yemen necessitates redressing the current balance of power between the Houthi movement and the various forces ranged against it by pressing the former to negotiate a settlement,” writes Hussam Radman in a new report from the Sana’a Center focusing on Saudi’s role in southern Yemen. The paper recommends implementing the Riyadh Agreement, with the hope that the “Houthis could be encouraged to soften their stance if an agreement succeeds in addressing corrupt practices and political patronage that opposition groups see in Hadi’s government.”

The United States has helped to prolong the conflict by disingenuously taking one side even as it pretends to be an honest broker for peace.

At least 15.6 million Yemenis live in extreme poverty, and face lasting economic uncertainty. Inflation is rampant, especially in the south, not only as a byproduct of the conflict but as a tool of war and control as factions vie for control of the central bank. A recent report from the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures at the University of Denver found that Yemen had lost out on $126 billion in potential economic growth over the course of the conflict.

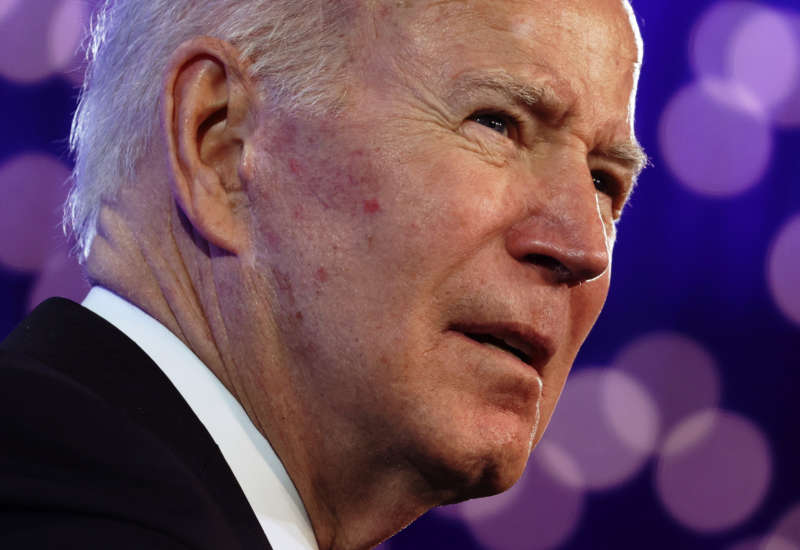

President Joe Biden made a commitment to end the conflict in his first major foreign policy speech in office. He cut off some support for the Saudi-led coalition in February 2021, breaking with the two prior U.S. administrations. The United States had previously been supplying intelligence and refueling support for Saudi and UAE air power, which ended under Biden.

Despite those pledges, Biden greenlit a massive, $650 million weapons sale to Saudi Arabia last November. The administration justified the sale on the grounds that the air-to-air missiles are categorized as “defensive weapons,” an absurd pretext that falls apart on even the slightest scrutiny. Even one of the conflict’s most ardent critics in Congress, Sen. Chris Murphy, joined in the administration’s circular logic.

Biden is reportedly considering redesignating Houthis as a “foreign terrorist organization,” following their attacks on the UAE. That decision could have disastrous effects on the civilian population, as humanitarian organizations often cease providing aid that could be seen as supporting a State Department-designated “terrorist” group. Matt Duss, foreign policy adviser to Sen. Bernie Sanders, harshly criticized the idea. “There’s little evidence that these designations do anything to produce better outcomes,” Duss tweeted. “They’re just a way to appease DC hawks, hobbling US diplomacy and constraining non-military options in the process.”

Unfortunately, for all of Biden’s talk about ending the war and isolating Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, his administration has done exactly the opposite. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan met with bin Salman in September, ostensibly to discuss human rights and to further peace in Yemen, but the administration has maintained the status quo regarding Saudi Arabia, bin Salman and the coalition’s posture toward Yemen.

The United States doesn’t have the capacity or the right to dictate the specific outlines of a durable peace in Yemen, but it has helped to prolong the conflict by disingenuously taking one side even as it pretends to be an honest broker for peace. That’s been true for the prior two administrations, and is true for Biden’s as well.