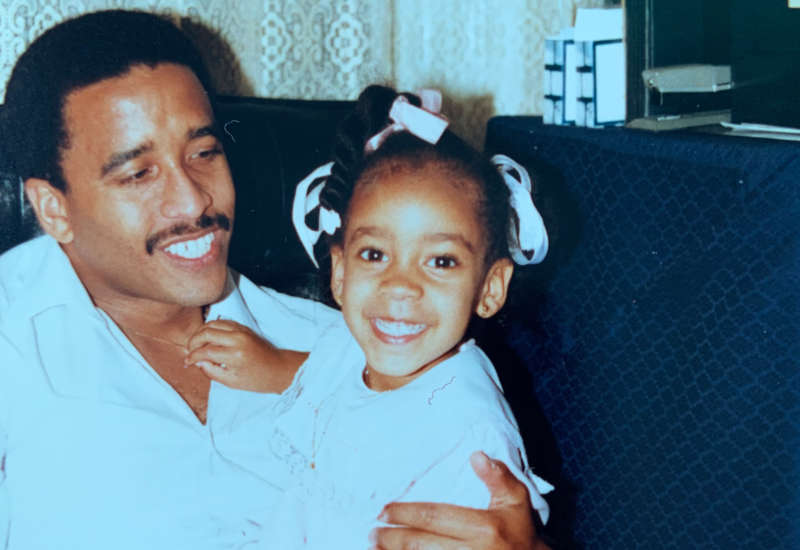

My father raised me to love Assata Shakur, to critique every institution and to love apple pie. Yes. The man who raised me on Black Panthers for Beginners, Pan-Africanism for Beginners, Malcolm X for Beginners and the protest poetry of Sonia Sanchez also had a lifetime love affair with the symbolic pastry of American traditionalism.

The story is that my father so loved apple pie as a little boy that my grandmother got sick of him asking her to make it and taught him to slice, spice and sugar the apples, add lemon juice and butter and put it in a store-bought crust himself. Over the years, he perfected his cinnamon-to-nutmeg ratio, his McIntosh apple selection standards so deliciously that at every extended family function, people asked after and waited for his pies. The demand grew so great that, of course, he had to bring on unpaid workers. How American.

My sister and I didn’t feel exploited, though, when he enlisted our help. We loved the apple-laden wooden table. The big metal mixing bowl, the juice of the stirred apples, brown with spice, tart with lemon. Rigorous taste-testers, we stole samples out of that bowl at every stage of the process. Between holidays, we would do a quick weekday version. Dad would buy all-natural sugar free apple sauce and we would add cinnamon, nutmeg and so much sugar that it ended up sweeter than anything they sold in the store. When I moved into my dorm room for college, my mother and aunties helped me set up and decorate. And my father brought his own nurturing offering: a giant case of organic instant oatmeal from the health food store, cinnamon apple flavored, of course. Perfect for a girl who could barely cook. Just add boiling water to the fill-line in the sturdy paper cup, and go.

These days, I still start the day with oatmeal. Every morning when I shake cinnamon and nutmeg into simmering coconut milk before I add the oats, the kitchen air brings me back to that sweet man who nurtured my militant critique. When I miss him the most, I add apples on top. On holidays, on my father’s birthday, or the anniversary of the day he passed away, my sister will invite her daughters into the sacred ceremony: a mostly homemade apple pie.

Do you have a story like this? I could write this tribute to my father all over again with pancakes, his other specialty. On my father’s first birthday after he passed, we went to his favorite diner and ordered what he would order, the Belgian waffle. When I can’t see his smile, when I can’t hear his voice, when he’s not there to celebrate a new victory with me, edible sweetness seems like the available proxy for how I want to feel.

My father died because he lacked access to health care. And so, recently I got a new doctor who taught me how to read the lab reports they get when they test your blood at a physical check-up. Guess what? There is a lot of sugar in my blood. Not quite diabetic, not quite pre-diabetic, but if there was a pre-pre-diabetic … I would be in that range. And now I am thinking about the emotional work sugar does in my life — the place-holding work that a sweet treat does for me when I can’t experience the comfort of a hug from a loved one.

“Give me some sugar,” the elder women say, and I gratefully give them a kiss on the cheek. But now, because of the pandemic, I don’t even remember the last time I kissed an elder.

“Give me some sugar,” the elder women say, and I gratefully give them a kiss on the cheek. But now, because of the pandemic, I don’t even remember the last time I kissed an elder. We are missing so much sweetness. But this year, like every year, the Valentine’s Day industry is churning out its own version of sweetness, conveniently available for same-day delivery.

I have been as complicit as anyone in this Valentine’s Day conspiracy. When I was in high school, my mom would gift me my favorite chocolates on Valentine’s Day morning — the ones with messages inside the foil wrappers — and I would share them with my friends at school, giggling as if the love messages were our fortunes. In college, I would buy bags of individually wrapped “fun-sized” candy bars and hand them out to strangers on and around the campus, savoring the sweetness of people’s surprised smiles. Sweetness should be portable, shareable, well-packaged. It should be available and easy, right?

But remember how I told you my dad raised me to critique everything? My father would remind us that on a capitalist planet, sweetness is war. Just like everything else. North American corporations ignore Indigenous land rights to tap maple syrup. The United States sent the contras to terrorize Central America to control the fruit industry. The extractive practices of corporate honey producers are part of a pollinator crisis that threatens the entire food supply. The Dutch East India company committed a whole genocide against the Bandanese to get a monopoly on nutmeg. And sugarcane itself?

The first plantation that used the forced labor of Africans kidnapped into chattel slavery was a sugarcane plantation in a place called Boca de Nigua on the island of Ay-ti (the Indigenous Taíno word for the island now shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Dictator Rafael Trujillo established the batey system to exploit Haitian workers under conditions too similar to plantation histories. According to the Batey Foundation, this system creates an underclass with “no public services, no legal protections, and no economic opportunities.”

In the early 20th century, when Dominican sugar workers rose up, led by Mamá Tingó, plantation owners sent scouts to the small islands of the Caribbean and recruited the poorest of the poor, including starving children, to do the work instead of improving the conditions. They carried these replacement workers to Santo Domingo in the airless hold of a ship.

My grandfather was one of those starving children.

I want to see the end of slavery in my lifetime. I want a love that can save your impossible life and mine. I want all our ancestors with us in their full dignity.

He told me about being sick in the boat the whole way over. He almost died from overwork and a wound from a bull on a Dominican sugar plantation at the age of 11. If two other workers — a husband and wife he had never met — had not decided to save his life, I would not be writing this. We would not exist. The decision of two exploited adult workers to brew herbs for a child, to provide him shelter and safety, to value his life in a context of expendability, is that sweetness, or the safety underneath what we call sweetness. The possibility of generosity, dignity, life-saving care. That couple became my grandfather’s health care system under impossible conditions.

On a Black Feminist Delegation to the Dominican Republic organized by Ana-Maurine Lara, I went to that first sugar plantation at Boca de Nigua. As I stood there, a black bull walked slowly out of a grove of trees, stepping on the remnants of sugar stalks. This wise animal may have been doing his own ancestral work, but as I looked into his eyes, the story of my grandfather came back to me and a message clear as these printed words: Do not eat any sugar for a full year, starting today.

And so, I did it. A year-long cleanse from the sugar cane economy in my blood. Every time someone offered me a sweet treat or asked me why I was eating differently, I had to tell a story as old as the origins of slavery, as close as my own blood. I told hundreds of people that year about how slavery started on a sugar plantation, but how it was also the site of the first rebellion of enslaved Africans in the Americas. I shared what Black feminist anthropologist Fatima Portorreal told me about how a woman from the Congo named Ana Maria led a historic revolt there, establishing the first Black communal government in the Americas. I told people how the Haitian revolutionaries so revered that site that they came to announce the end of slavery right there, on the spot where I stood. I learned something about my capacity that year. About how if you can find the beginning of something, you can find the end. I learned the feeling if not the name of something I want more than sweetness.

That cleanse was years ago, and I am still in the process of defining what exactly it is that I crave, with my mouth, with my hands, in my heart. But I know this much — I want to see the end of slavery in my lifetime. I want a love that can save your impossible life and mine. I want all our ancestors with us in their full dignity. I want solidarity and care through whatever comes. And I suddenly remember that before he taught me to sugar the apples, my father showed me the proper way to hold a knife.