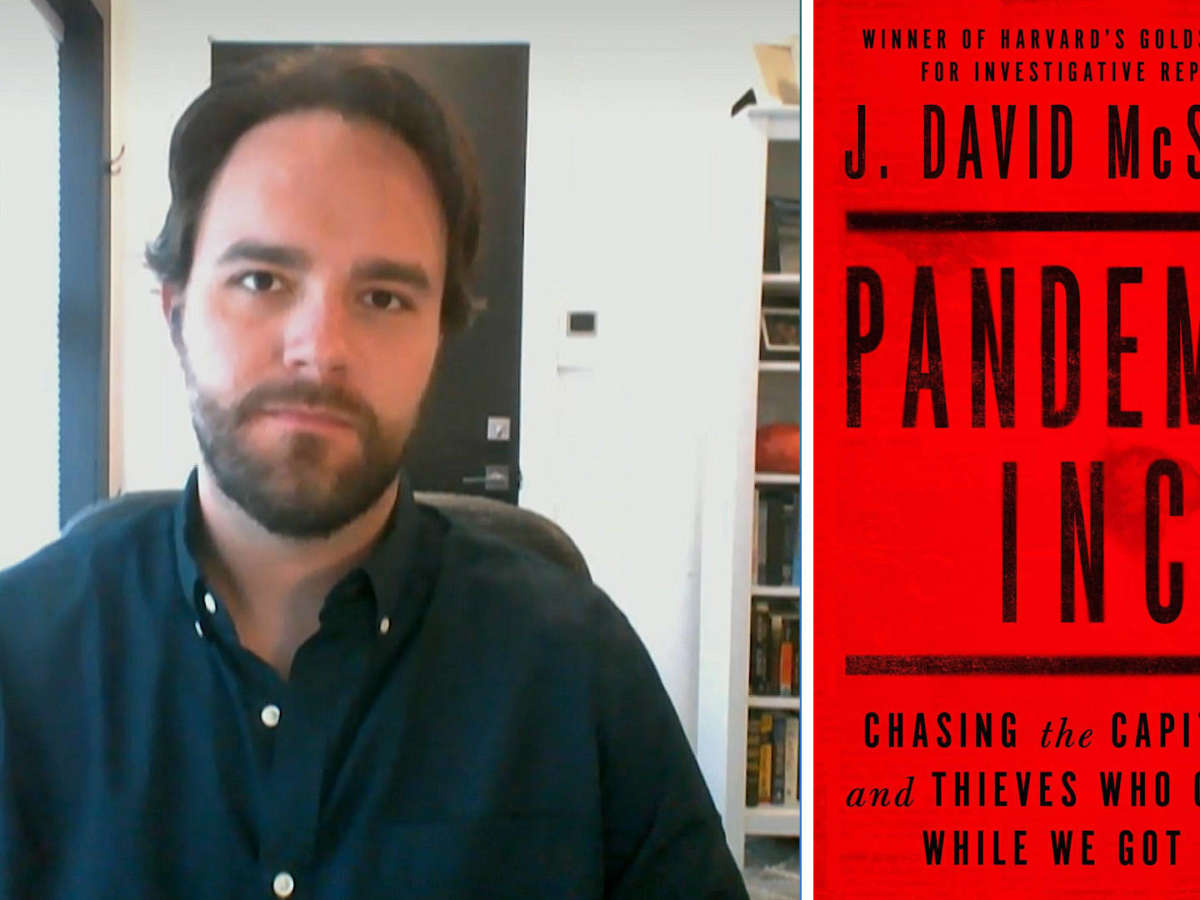

In Pandemic, Inc.: Chasing the Capitalists and Thieves Who Got Rich While We Got Sick, ProPublica investigative reporter J. David McSwane tracks pandemic federal relief funds and finds many contracts to acquire critical supplies were wrapped up in unprecedented fraud schemes that left the U.S. government with subpar and unusable equipment. He says an array of contractors were “trying to take advantage of our national emergency,” and calls the book “a blueprint of what not to do” during the next pandemic.

TRANSCRIPT

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

We end today’s show with ProPublica investigative reporter J. David McSwane. His new book is out today. It’s called Pandemic, Inc.: Chasing the Capitalists and Thieves Who Got Rich While We Got Sick. This week Dave wrote a viral Twitter thread about the book that began, “Let me tell you a crazy story. It’s consumed 2 years of my life. As COVID-19 shut down the world in April 2020, I decided to follow the money. I began with a call to a no-name federal contractor who’d somehow landed a $35M deal for masks. Hours later, I’m on a private jet.” Again, those the words of J. David McSwane.

Welcome to Democracy Now! Congratulations on the publication of your book today. So, take us from there. Why did you go on that private jet?

J. DAVID McSWANE: So, these are the early weeks of the pandemic, late April, early May 2020, really scary times, no vaccine, masks in short supply, our hospitals overrun. And this contractor, who I had found in federal purchasing data, had really come out of nowhere and had a really sizable deal that stood out. But in addition to that, he was supplying, supposedly, 6 million masks to the Veterans Administration, which oversees the largest hospital network in the country. So he had a pretty vital role in our pandemic response. And just sort of doing the due diligence, I wondered how he got this deal, and called him, and he ended up saying I could tag along on this private jet, and in doing so, over the course of maybe 72 hours, flying first to Georgia and then to Chicago, realized that he didn’t have any masks. He had claimed that they were, you know, bought out from under him. Next, he had a new line on masks. It involved some interesting characters. And slowly but surely, as I’m sort of observing this, I began to wonder if the whole thing was made up and if in fact he had conspired to defraud the federal government.

And, you know, we didn’t know everything then, but this was really crucial information that I felt the American public needed to know, so we reported what we knew. And that really set me off on more than a year of reporting, following around not just federal contractors but people who entered this space, sort of seeing the chaos cascading down from the federal government through states and into cities, and, you know, just over and over, found these just sort of bizarre characters doing odd things and really just trying to take advantage of our national emergency.

AMY GOODMAN: So, what happened with Robert Stewart? I mean, he didn’t get this money, a loan. He was given this money by the U.S. government. And what happened to the masks?

J. DAVID McSWANE: Well, I should clarify: He hadn’t been given the money outright. The federal government, unlike some states, was under the — working under the idea that, “Well, we’ll just hand out contracts all over the place, and we’ll pay if stuff is delivered,” which they said was, you know, sort of “no harm, no foul.” But what they were doing was they were flooding these big contracts into this market full of brokers and investors and everyone, and they’re seeing, “Well, the federal government is willing to pay $6 for a mask that used to cost $1.” So, while he didn’t collect any money because he ultimately didn’t deliver any masks, and was ultimately charged on three counts of fraud, others did get paid for the delivery of subpar equipment at times.

I have one example in Pandemic, Inc., the book, of a contractor who had stood up a company and by the end of the week had a sizable deal with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to deliver test tubes. Those test tubes were not in fact test tubes; they were mini soda bottles that had been sort of rounded up with literal shovels by temp workers in a hot and unsterile warehouse in Houston. And the federal government ended up accepting those and paying this vendor, even though those non-test-tube test tubes were completely unusable. So, there was an array of folks who entered this space, some of whom managed to get paid, some of whom didn’t, and some of whom ended up dealing with law enforcement.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to play short video you recorded and are sharing now for the first time, when you stopped by Fillakit’s warehouse outside of Houston, Texas, on June 10th, 2020 — again, a few months into the pandemic. You later reported on how this company got a $10 million FEMA contract for test tubes but gave them mini soda bottles instead. In this video, you approach the warehouse’s loading dock after the garage door opens. You can see workers inside holding shovels and tiny soda bottles. Then, Paul Wexler, wearing an Astros T-shirt, shouts at you to leave. As you respond, Wexler slams the door shut. This is a clip.

PAUL WEXLER: Can we help you?

J. DAVID McSWANE: Yeah, I’m trying to talk to Mr. Wexler.

PAUL WEXLER: [inaudible] No trespassing. Leave.

J. DAVID McSWANE: I’m not on your property.

PAUL WEXLER: Leave.

J. DAVID McSWANE: I’m not on your property.

PAUL WEXLER: You’re on our property.

J. DAVID McSWANE: Are these sterile vials you have here? How are you sterilizing these vials, sir?

PAUL WEXLER: You’re going to get hit by this [inaudible].

J. DAVID McSWANE: Are these sterile?

AMY GOODMAN: So, can you describe what happened next and what was inside, actually?

J. DAVID McSWANE: Sure, yeah. That wasn’t exactly how I wanted to approach that story. You know, I’m not in TV and don’t love the theatrics. But I realized that I needed some evidence to back up what we were hearing from sources, so I turned on my cellphone. I accidentally took it upside down. I’m holding my notepad and my pen and putting on my mask, so it was a little bit chaotic.

But I was able to observe and to document that, you know, this was a warehouse, nondescript. The only indication that the company was there was a low-stock piece of paper with some clip art on it. And these workers — some of them wearing masks, some not — were rounding up these soda bottles with literal shovels, moving them from one bin to another. Some were squirting in saline, which was sort of — it’s not the buffer you’d like to see in this sort of test kit, which is the PCR test, the real deal test that we were really needing at the time. I mean, our national response was incredibly behind. Testing was a huge part of that. And seeing that none of the protocols you need for those sort of tests, including a refrigerated truck — instead, they had a rented Enterprise truck — none of those things were being followed, so these were highly suspect tubes, and they were being sent to FEMA, which was forwarding them to all 50 states and territories. So, having that video, for me, seemed important. I needed to say that these particular tubes were the product being delivered, and they matched what we were seeing from public health officials in various states.

AMY GOODMAN: So, ultimately, what happened?

J. DAVID McSWANE: Ultimately, what happened is, because the federal government, FEMA, accepted those soda bottles filled with saline, as per their contract, and delivered them to states, contract experts we talked to said it would be hard to make a case that the federal government didn’t get what they paid for, because they accepted them, and they were forwarded to many states. And I talked to public health officials who said this set back their testing plan. It set them back weeks. The tubes, in addition to probably being unsterile, they didn’t fit standard lab equipment. I mean, this would not have been hard to catch by any public health official, because the states noticed it right away. No one wanted these things. But the company was paid. And to my knowledge, there’s been no law enforcement action in response to that particular deal, though the owner is facing some lawsuits related to other allegations of fraud.

AMY GOODMAN: So, can you talk about the respirator deal with AirBoss Defense Group that was directly ordered by the White House? You found that the key Trump adviser, very much in the news right now, referred by the committee for criminal prosecution, Peter Navarro, awarded the deal to AirBoss after it hired retired four-star Army General John Keane to reach out to him shortly after Trump had awarded Keane the Medal of Freedom.

J. DAVID McSWANE: Right. In the book, Peter Navarro, in my research, he sort of stood out to me as a bit of a tragic figure. He was one of few in the administration who really took the threat seriously early on. And, you know, he’s got bravado. He’s brusque and kind of a no-BS kind of guy in the White House. He wanted to take charge in what he called “Trump time.” At the same time, the administration was trying to ignore the pandemic altogether. So, behind the scenes, he does something really remarkable. He takes federal government purchasing into his own hands. And for obvious reasons, you can’t have political appointees in a political office, the White House, deciding who gets multimillion-dollar deals and who doesn’t. And this was sort of the first indication that I found — and found it in just like an obscure entry in federal data — that the White House was ordering these deals.

And this particular company is a real company, Canadian-controlled company, ultimately. They produce rubber products. And these were for the sort of high-end respirators you saw with like Dustin Hoffman wearing in Outbreak. And, you know, they got a pretty large deal. And we noticed that the White House was ordering it. And that was sort of our first indication that, you know, we think the federal response right now is to just throw money all over the place. And if you have some political connections, that helps. But I found, weeks later, that you didn’t even need that. You just needed an LLC and an email, and the federal government would give you a deal for things that you may or may not have.

AMY GOODMAN: And again, to clarify, we’re talking about AirBoss, not Airbus.

J. DAVID McSWANE: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: But, David, finally, if you can talk about what this all means — I mean, we’re not done with this pandemic yet — and also the billions of dollars that were spent?

J. DAVID McSWANE: Right. I mean, it’s fair to assume, from the outset, that we were going to spend a lot of money. We weren’t prepared. We needed to find supplies. Healthcare workers were in danger and dying. So you expect some of that. But I was really struck by how chaotic it was. You know, even though this was the Trump administration, I expected there to be some inertia, just within the government bureaucracy, to ensure that we were buying real things and we were getting a decent deal and we weren’t wasting our time with conmen, and found that we were so flat-footed, so ill-prepared. Our national stockpile had something like 1% of what we needed to address, really, that first wave of the pandemic. That’s how bad it was, that our national well-being really rested in the hands of these mercenaries, who smelled blood in the water and really sought riches.

So, I view the book as a blueprint of exactly what not to do, and sort of a call to better prepare so that we’re not in this situation again. But more than that, you know, I’m conscious that we’re all feeling pandemic fatigue, and we’d love to move on. I sort of look through the lens the whole time, in writing the book and in my reporting, to answer the question: What does this mean about us? And at the end of the day, while the book is an artifact of the pandemic, I think it’s really a story about who we are, our worst impulses, what happens when we just sort of have this religious adherence to free markets, when experts say we really should have had a very visible hand on this and directed supplies, figured out who needed things, and made sure that our money was being used wisely.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, J. David McSwane, I want to thank you for being with us, investigative reporter with ProPublica, new book out today, Pandemic, Inc.: Chasing the Capitalists and Thieves Who Got Rich While We Got Sick. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.