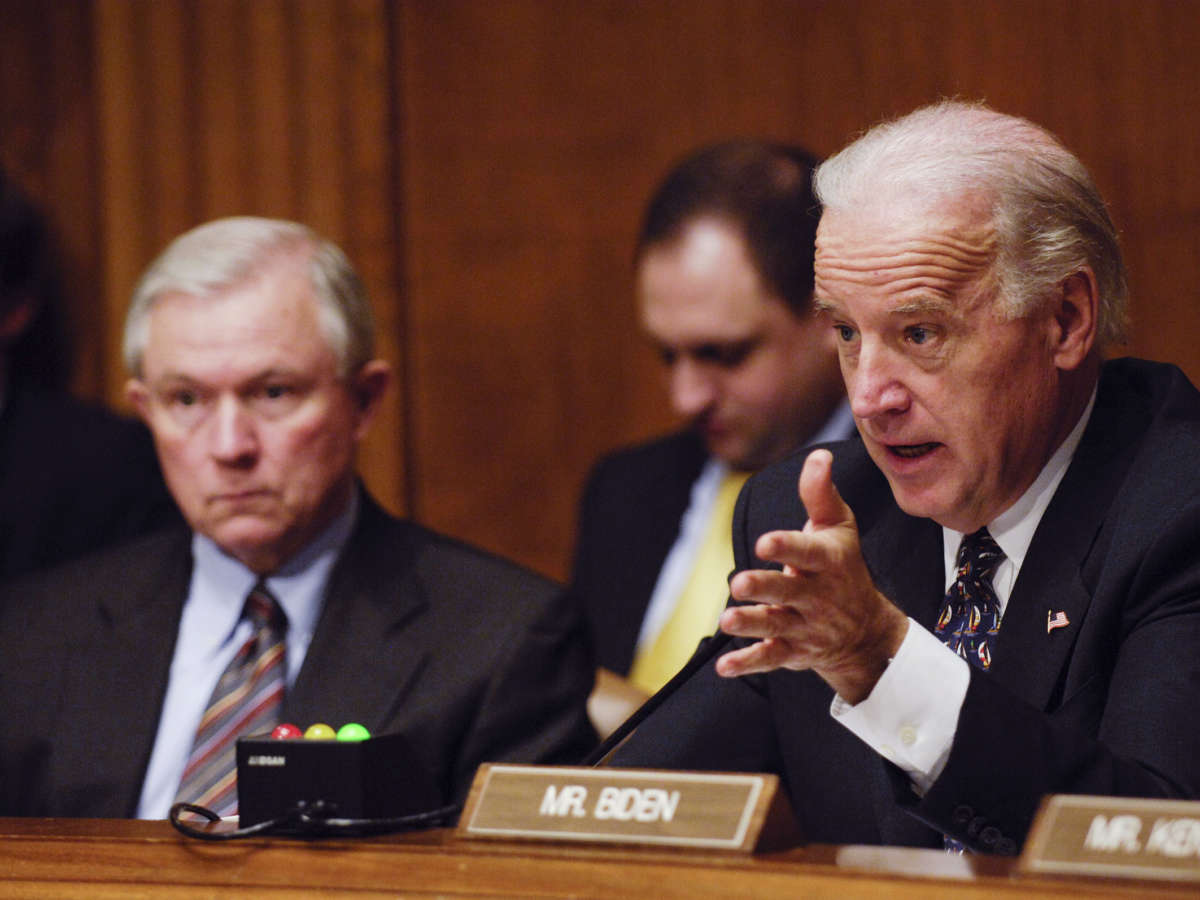

The war on drugs will not end under President Joe Biden, at least for now, but change is afoot. The overdose crisis has forced federal policy makers to embrace harm reduction policies, roughly 40 years after activist collectives and underground clinics began distributing clean syringes and other safety supplies to drug users, strategies proven to prevent overdose deaths and the spread of disease.

In a historic first, the Biden administration presented a National Drug Control Strategy to Congress last week that calls for the expansion of harm reduction services such as syringe exchange programs to combat the overdose crisis. This is a grassroots victory: Activists and public health advocates have spent decades fighting for federal support for harm reduction, a broad term encompassing a range of evidence-based services for helping drug users stay safe and healthy that are provided without stigma or judgment.

Polls show harm reduction enjoys broad public support, and bipartisan majorities of voters say the drug war has failed and possession of small amounts of drugs should be decriminalized. However, Biden’s support for harm reduction is not untainted. Faced with right-wing backlash, the president is simultaneously doubling down on the drug policing and anti-trafficking efforts known as the “war on drugs,” an approach that critics say has fueled widespread racial injustice, mass incarceration and a wave of drug-related deaths.

Rates of fatal drug overdose increased under former President Trump before reaching a record high during the pandemic, which isolated drug users from harm reduction services and social supports. Nearly 107,000 overdose deaths over the past year reveal that the government’s “punitive, carceral approach” to drugs is extremely harmful, according to Daliah Heller, the vice president of drug use initiatives at Vital Strategies, a group that promotes harm reduction.

“It is an approach that rests on a racist and punitive foundation with destructive and predictable consequences — filling up our prisons and jails, breaking up families and communities, and producing the worst overdose crisis in history,” Heller said in a statement.

The war on drugs is widely recognized as racist violence. The police who murdered George Floyd in Minneapolis attempted to blame Floyd for dying under the unrelenting knee of a police officer because he used drugs. Breonna Taylor was shot dead by police during a “no-knock” drug raid in Louisville, Kentucky. Their deaths sparked widespread protests against police and against anti-Black racism, but under attacks from the right, Biden and Democrats in Congress have refused to take steps to decrease police funding, opting instead to do the opposite.

Biden’s “drug control” strategy reflects a shift that began during the Obama administration, when the overdose crisis was intensifying and policy makers promoted public health responses rather than relying solely on prevention and law enforcement. The results of this shift — and the government’s response to the overdose crisis more broadly — are extremely unequal. Studies show that the number of white people dying of overdose in several states has slowed while the number of people of color dying of overdose is skyrocketing.

Since 2020, the rate of overdose mortality among Black people has increased by nearly 49 percent, and Hispanic or Latinx communities have experienced a 40 percent increase in overdose mortality, according to Grant Smith, the deputy national affairs director of the Drug Policy Alliance. Native and Indigenous people have seen the highest increase of mortality among all ethnic groups.

The Biden administration states in its drug control strategy that these racial disparities are driven by stigma and discrimination that people of color experience when seeking health care or addiction treatment. However, Smith said stigma and discrimination are rooted in institutions, including in the racist drug war that the administration is continuing to fight.

“This cannot continue,” Smith said in a statement. “Criminalization approaches only saddle mostly Black, Hispanic and Indigenous people with criminal legal records and often incarceration, which increases their risk for infectious diseases, overdose and death.”

The decriminalization of drugs and the people involved with them is not mentioned anywhere in Biden’s drug plan.

Still, the inclusion of harm reduction in the National Drug Control Strategy is a massive paradigm shift reflecting decades of work by grassroots activists. Harm reduction is proven to save lives, but backlash from tough-on-crime politicians has prevented the federal government from supporting syringe exchanges and other harm reduction programs for years.

Echoing the language of harm reductionists, the Biden administration pledges to “meet people where they are” and expand access to addiction medications, drug testing supplies, syringe exchange programs and naloxone (the opioid antidote used to reverse an overdose). The administration is also directing federal agencies to integrate harm reduction into the medical system and study barriers to addiction treatment, housing, employment and health care for people who use drugs.

Biden’s recent budget request includes $355 million in additional funding for the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Biden’s GOP opponents smell red meat. Despite rising rates of fatal overdose under Trump and over the past decade, Republicans are attempting to pin the overdose crisis on Biden by wrongly conflating the humanitarian crisis on the border with Mexico with drug trafficking. They have also used racist dog whistles to attack harm reduction programs, including safe consumption sites where people use drugs under medical supervision, which were prosecuted under Trump but are already saving lives under Biden.

Biden’s recent budget request includes $355 million in additional funding for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the law enforcement agency charge with waging the drug war that already enjoys a $3.28 billion budget. If approved by Congress, the funding would be the largest increase in DEA spending since the height of the drug war in the 1980, according to the Drug Policy Alliance.

Despite five decades of drug war waged around the world, law enforcement has never succeeded in stamping out the illicit drug trade in the United States, not to mention other drug-producing countries such as Colombia, Afghanistan and Mexico. Rates of fatal drug overdose only increased after a crackdown on prescription pills in the U.S., which left patients in agony and pushed people toward fentanyl and illicit benzodiazepines that are fueling the overdose crisis (along with other drugs such as alcohol and methamphetamine).

Experts warn that law enforcement efforts to disrupt the supply of fentanyl at the border and on the streets will be unsuccessful while making the drugs people use more dangerous and unpredictable, which is a major cause of fatal overdose. Meanwhile, criminalization guarantees that people involved with drugs will continue to be punished by police and dragged into jails, prisons and drug courts, which vastly increase the risk that a drug user will suffer a fatal overdose. Drug overdose is the most common cause of death among people recently released from prisons, and the third leading cause of death within the nation’s local jails, according to the Vera Institute of Justice.

Federal efforts to decriminalize drug possession and legalize marijuana have so far been unsuccessful, but progress has been made in some states. The number of people dying of drug overdose in jails and prisons has skyrocketed over the last decade, but prison officials have largely refused to provide addiction medication that people depend on once they are incarcerated. After a push under President Obama to provide addiction treatment to federal prisoners fell flat, the Biden administration is pledging to make addiction medication available to 100 percent of federal prisoners diagnosed with opioid use disorder by 2025.

Heller said the administration’s turn toward harm reduction is a “step in the right direction” but more needs to be done. Some states still restrict access to naloxone, for example, and making the medication universally available over-the-counter is an urgent priority. “Robust recognition and enforcement” of anti-discrimination protections for people who use drugs is also desperately needed, Heller said.

“Current restrictions on access to medications and other life-saving services means that people continue to die unnecessarily from preventable overdose,” Heller said.