When Congress passed a $1.5 trillion omnibus spending bill in March, anti-hunger advocates were stunned that appropriations to ameliorate child hunger worsened by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic were not included.

A month earlier, more than 2000 organizations signed a letter, initiated by the 52-year-old Food Research and Action Center, to demand that Congress continue to allow schools to sidestep a host of rules that, pre-COVID, means-tested student eligibility for school breakfast and lunch programs, and restricted what was served and where it was served.

“The COVID pandemic is far from over,” the letter stated. “Families continue to need support, particularly Black, Hispanic and Indigenous families who disproportionately lack reliable access to healthy meals…. School nutrition departments and community sponsors still struggle to operate under the unique circumstances created by the pandemic.”

Those unique circumstances, of course, shuttered schools in March 2020, and the letter reminded lawmakers that because of the unprecedented health crisis, Congress gave the U.S. Department of Agriculture — which oversees school meals programs — the authority to issue nationwide child nutrition waivers “to address access and operational challenges” created by the fast-spreading virus.

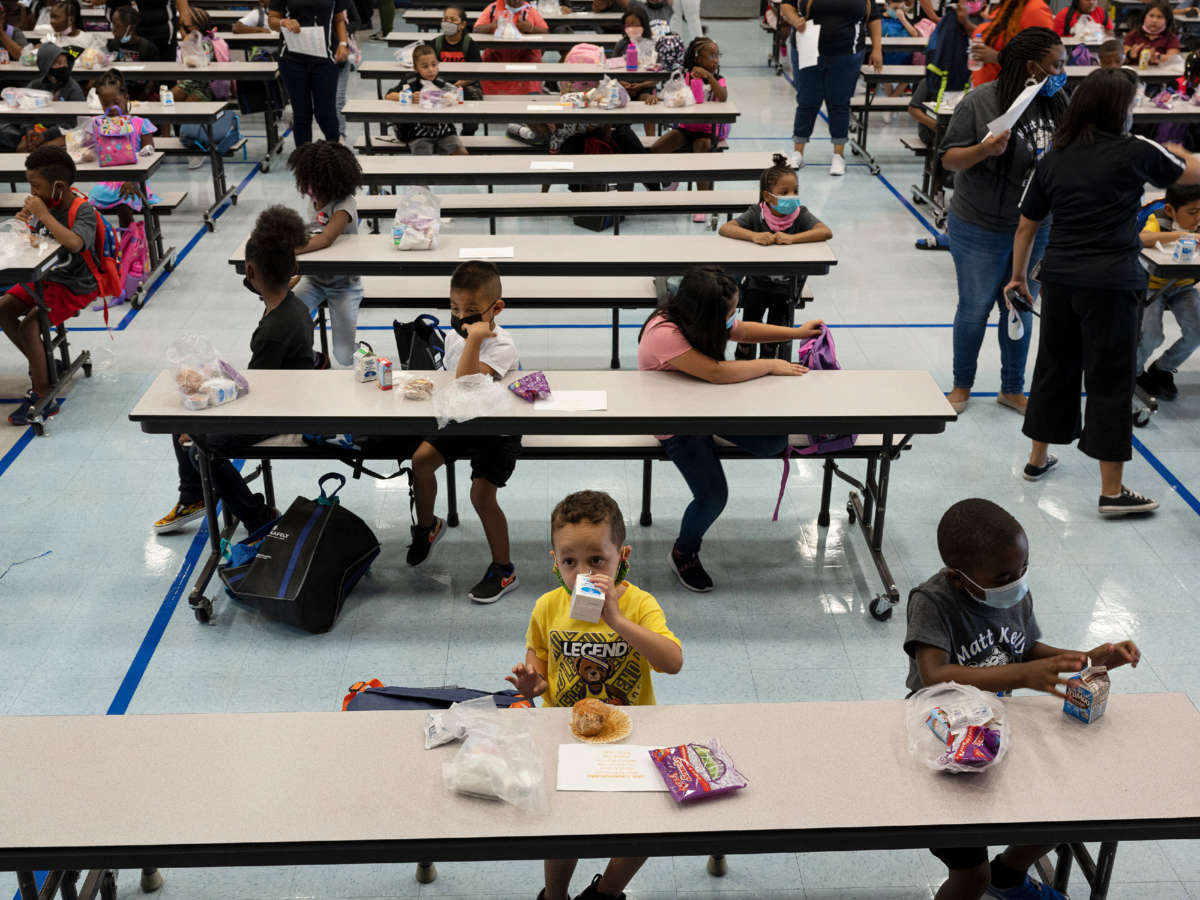

In short order, schools began to make grab-and-go bag lunches and breakfasts available for pick-up at designated sites; allowed school buses to drop off meals at students’ homes; and extended eligibility for meals to every student, regardless of family income. When schools reopened months later, no-cost meals — and in some cases after-school snacks — continued to be provided to each and every pupil.

But unless Congress acts, these changes will expire on June 30.

Advocates say that this will have a catastrophic impact, not just on students, but also on food service staff and school administration.

Without an extension of the waivers, schools will have to revert to a three-tiered system: free meals given to those at or below 130 percent of federal poverty guidelines ($23,803 for a household of two; $36,075 for a household of four); reduced fee meals for those between 131 and 185 percent of the guidelines (up to $33,874 for two and $51,338 for four); and full-payers, whose per meal fee is set by local school authorities.

Before the pandemic, “we spent millions of dollars a year on paperwork,” Joel Berg, CEO of Hunger Free America, a New York City-based advocacy and direct-service organization, told Truthout. “It was and is counterproductive. We know that food is key to educational advancement. If a kid hasn’t eaten breakfast, by 2 pm their head will be on the desk and they will be napping. Universal school meals increase attendance, improve health and give kids a good start in life. When we force people to fill out forms to prove they’re eligible, we’re essentially spending money to keep food away from kids who need it.”

Even if lawmakers do not care about the morality of letting kids go hungry, the bottom line is that kids can’t study and learn unless they’re well fed, Berg said. At the same time, the pandemic has made providing high-quality, nutritious food increasingly difficult.

“Schools are short-staffed and food prices have skyrocketed,” Diane Pratt-Heavner, director of media relations at the School Nutrition Association, a professional association representing more than 50,000 food service workers and agencies, told Truthout. “But thanks to the waivers, schools have been reimbursed at a rate of $4.56 per lunch as opposed to $3.75, which is what they received pre-COVID. This makes a big difference.” Going back to the lower reimbursement rate, she explained, will be devastating because of escalating food, labor and fuel costs.

“The idea is that it is time to get back to normal, but what schools are facing is not close to normal,” Pratt-Heaver said. “There are huge supply chain issues and many families are struggling with unemployment, the high cost of gasoline and health issues. People who are slightly above the federal poverty threshold are still having trouble making ends meet and if their kids are no longer eligible for free meals, it will be a huge loss.”

Jillien Meier, director of No Kid Hungry, a campaign of Share Our Strength, a national nonprofit that works to end hunger and poverty in the U.S. and throughout the world, told Truthout that the waivers have given schools “a cushion and breathing room” to mitigate shortages.

“There has been difficulty finding bread, ketchup and ground beef,” she said. “We have been hearing stories of school staff going to Kroger’s or Costco at 4 am to pick up supplies. Many, many people are going above and beyond to make sure kids have enough nutritious food to eat. Not extending the waivers is hitting these programs when they’re already down. Everyone wants to return to normal, but normal isn’t here yet. The waivers allowed non-congregate meal sites to offer food and authorized the bundling of more than one meal at a time when schools are closed. This was helpful to staff preparing the food as well as to food recipients.”

These measures have been extremely important for staff working in the Paradise Unified School District in California, an area that was decimated in 2018 by wildfires that burned 240 square miles and killed 86 people. “The waivers that were put in place due to the pandemic have made it possible to serve more of our community, not just our K-12 students,” Tanya Harter, director of food services for the district, told Truthout. As a result, kids enrolled in a daycare center and charter school were also fed.

Tanya Harter (center), the director of Paradise Unified School District Food Services, poses with her coworker Jennifer Faria (left) and two parents who came to pick up pandemic-era “to-go” meals for their schoolchildren.Courtesy of Paradise Unified School District Food Services

Harter’s colleague, Melissa Crick, is the president of Paradise District Schools, a locale with six schools serving 1487 students, at least 30 percent of whom lack a permanent home. Many families are living in trailers, cars, temporary rentals or are doubled up. High unemployment, far distances between homes and schools, and astronomical gas prices have made it extremely difficult for families to access food without help from the district.

“Hundreds of people need food and jobs, but gasoline is $5.60 a gallon so a 20-mile drive puts a huge strain on the already strained resources of most families,” Crick said.

In addition, the district was given short-term federal recovery funds following the wildfires; these funds are set to expire before the next academic year begins. “If the state does not come in to help, we will have to make layoffs in the schools,” Crick said. “About 90 people — teachers and staff, including food service workers — will have to be terminated.”

If the remaining staff have to process applications for free-or-reduced price meals, it will exacerbate this highly fraught situation, she added.

“It makes no sense to take away critical programs when we know that a tidal wave of social and emotional issues will continue to come at us,” she continued. “Students are reporting more suicidal ideation and are seeking a record number of counseling appointments. We should be increasing services, not decreasing them, and not just here in Butte County, but nationwide.”

“Without Eating, I Can’t Focus on School”

School meals have been a lifeline for Dawn Zephier and her five children. The family fled a “bad situation” in South Dakota last August and now live in Las Cruces, New Mexico. “When we arrived, I rented a motel room,” she begins. “There were nine of us living together at that time, including two grandchildren, and I thought that we’d stay in the motel for a week or two, tops. But there is a crazy affordable housing shortage here and it was really hard on us. We had to stay in the motel for four months.”

Although the family now lives in a four-bedroom house thanks to a Section 8 subsidy, Zephier says that the free school meals have been a lifesaver.

Israel, her 17-year-old son, agrees. School meals get a bad rap, he begins, but they are often enjoyable. “I take food even if I’m not hungry,” he says, “and even if I don’t like it because someone else in my house might like it. I know that without eating, I can’t focus on school. If I’m hungry, I need to eat something, even if it’s just a stick of gum.”

“When you don’t know when you will eat again, you might as well chow down until you can’t eat anymore,” says 18-year-old Eric Zephier (right), who has relied on free meals at his high school. Eric appears here with his brother Israel and his mother Dawn.Dawn Zephier

His brother Eric, 18, adds that when he first enrolled in the school, he did not know that he could take more than one helping of the meals served. “One of the guys who makes the food told us that we can take seconds or even thirds. So, hey, it’s free, and when you don’t know when you will eat again, you might as well chow down until you can’t eat anymore.”

And, while both he and Israel work part-time, he says that not only have the free meals enabled him to help his mom and siblings, they have sensitized him to the needs of other low-income people.

“When we were in South Dakota, my son told me that a boy had his lunch tray taken away because his family owed money to the school for his meals,” Dawn told Truthout. “Why would anyone humiliate a child this way? No child should have to deal with this kind of bullying; every kid should have enough food to eat.”

Anti-hunger advocates are in complete agreement and are working with Congress to see if waiver extensions can be added to pending legislation.

“We need Congress to act now or the next school year will be derailed,” Meier says. “Yes, there are a lot of competing issues and it is easy for something like school meals and nutrition programs to get lost, but advocates are not calling it a day. All of the anti-hunger groups have been relentless in pushing Capitol Hill and the White House to do something, and we are looking for any bill that can be amended to include waiver extensions. We know that time is of the essence. We also know that it is quickly running out.”