On May 11, the Department of Interior released a Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative investigative report, the first official accounting of the hundreds of federally supported institutions that, for generations, worked to culturally assimilate Indigenous children to white American norms.

The report identifies seven institutions from Hawaii as fitting the criteria to be considered boarding schools. This is surprising because neither scholars nor many Native Hawaiians have historically viewed these schools as part of the same system as Indian boarding schools.

Hawaii’s inclusion in the report is complicated in a number of ways. For one, it raises long-standing debates over federal recognition of Native Hawaiians, who have a different, less established legal and political status than federally recognized Native American tribes with tribal governments.

Many Native Hawaiians do not see the Department of Interior as having appropriate jurisdiction over Hawaiian affairs; many believe in pushing for a full restoration of independence from the United States. The report also noticeably makes some significant errors in reference to Hawaii — such as designating one school as located at “Kawailou.” There is no such place as “Kawailou.” This is likely a misrecognition of an actual place, Kawailoa. Further, it is unclear to what extent, or who, among the Hawaiian community, was consulted in the writing of the report.

Despite such issues, the report might be an occasion for Native Hawaiians and the public more broadly to learn more and grapple together with the legacies of the institutionalization of Hawaiian children in the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries. This history in Hawaii bears both striking similarities as well as significant differences from Native American contexts.

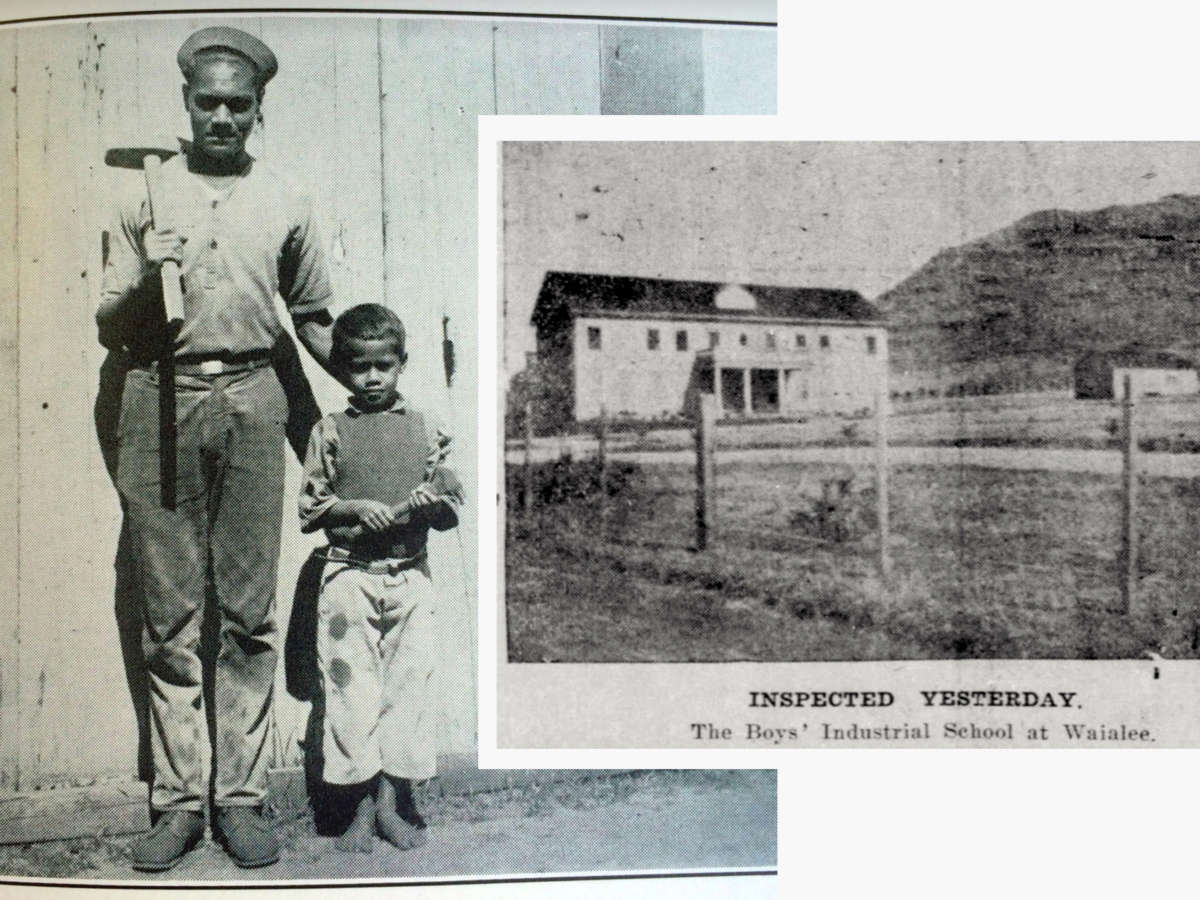

I know this because I am a Native Hawaiian historian who, for the last several years, has been trying to find out everything I can about the histories of the government-run Kawailoa Training School for Girls and the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys, both of which are named as boarding schools in this new report, with the former being listed in the report as the “Industrial and Reformatory School for Girls (Maunawili, Koʻolaupoko)” and the latter being listed in the report as “Industrial and Reformatory School (Waialee, Waialua).”

I came to this research because my tūtū (grandma), Lilia Awo, worked as a housemother at the girls’ school later in its history, from roughly the 1960s. From family stories of her experiences there, and after coming across an interview of a young girl who was a ward at Kawailoa in the 1930s, I really wanted to know what the origins of these “schools” were and what role they played in repressing Hawaiian culture and dispossessing Hawaiians from their land.

My research, involving records at the Hawaii State Archives as well as both English-language and Hawaiian-language newspapers, is ongoing. What I have found so far is a complex history that dates back to the Hawaiian Kingdom. The first reformatory opened in 1865, according to the archives. The reformatory was at first seen as a progressive measure to keep youth who had committed petty crimes such as theft or truancy from going to prison, where it was assumed they would form relationships with adult criminals and go further down a bad path.

Though still an independent country at this point, the Hawaiian Kingdom was under pressure to prove it was a “civilized” equal to Western countries. Many white settlers advised the monarchy, to their own advantage, as white-owned sugar plantations boomed. A cadre of these sugar plantation owners overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, instituting their own government. The U.S. federal government did not originally sanction the overthrow. But in 1898, the U.S. annexed Hawaii, and officially made it a U.S. territory in 1900.

The government-run Kawailoa Training School for Girls and the Waialeʻe Training School for Boys … are named as boarding schools in this new report.

As the federal report notes, the territorial government deepened colonial efforts to dispossess Native Hawaiians of their land and culture. In 1903, the reformatory moved to Waialeʻe on the rural North Shore of Oʻahu from its first location in the outskirts of Honolulu. Boys continued to be sentenced to what was now called the Waialeʻe Industrial School for Boys, for crimes like stealing or skipping school, according to my research in the Hawaii State Archives. Not incidentally, this location was closer to sugar and pineapple plantations, where the boys kept at the school were often sent to work, effectively uncompensated, as part of their “training.”

Around this same time, a separate correctional institution for girls also opened. Girls were usually sentenced for perceived sexual transgressions, called “waywardness” or “immorality.” This stark, gendered difference in the way young women were criminalized is intimately tied to Hawaii’s colonization. Pre-colonial ideas about gender in Hawaii emphasized balance and complementarity, not patriarchy, legal marriage and female domesticity.

The girls’ school also eventually moved to the country in 1929, at Maunawili on the windward side of Oʻahu, where girls did agricultural and domestic work to support the running of the school. The aim was generally to make the girls into maids or laundry workers, according to my research in the state archives. Such training is identical to the roles many Native American young women were forced into at boarding schools as well.

Throughout the history of these government-run institutions, Native Hawaiians made up the majority of the population. But they were not the only ones there. Hawaii’s immigrant communities, brought in to provide more labor for the sugar plantations, were also represented in smaller percentages, including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, Puerto Rican and Portuguese immigrants, among others.

The multiethnic character of these places are one reason, I suspect, why they generally have not been understood as of a piece with Indian boarding schools, which were largely solely populated by Native Americans (though usually from many different tribes in an attempt to dilute tribal affiliation and kinship ties). So too the fact that the government-run institutions took in only children convicted of crimes, rather than targeting Native Hawaiian children wholesale, puts them more closely in the vein of other industrial and training schools that operated in the continental U.S. and targeted “delinquent” children of many races.

These institutions forcibly separated children from their families for years, even decades, at a time.

However, as the federal report notes, alongside the training schools in Hawaii were also schools like Kamehameha Schools (a still-operating, now private school for Native Hawaiian children founded by the will of a princess of the Hawaiian Kingdom) and missionary-run schools which implemented similar programs of assimilation.

While many Kamehameha Schools alumni have been publicly debating their alma mater’s inclusion in the federal report, I hope the related but also distinct histories of the training schools are not overlooked. These institutions forcibly separated children from their families for years, even decades, at a time. In this, they were much more similar to Indian boarding schools than Kamehameha Schools.

The era when Hawaii was a U.S. territory (1900-1959) has often been conventionally portrayed as benign, with little resistance on the part of Native Hawaiians who supposedly uniformly celebrated Hawaii becoming a state in 1959. Yet further attention to these institutions paints a markedly different picture of this time. Given the ease with which a family might lose their child for years due to a petty violation of the law, or for girls, even the mere suggestion that they improperly “associated with boys,” the presence of these “schools” were likely a powerful damper on more widespread resistance to U.S. colonialism in the territorial period.

Undoubtedly, there are intergenerational impacts caused by this history that we have yet to process. So many family ties broken, so many cultural understandings of ourselves destroyed. Native Hawaiians remain disproportionately incarcerated today. As our people begin to process this history and this report, we clearly have a lot to learn from, and much to mutually support, including Native American, Alaskan Native and Indigenous communities in Canada who have been directly reckoning with this history for a longer time.

While I do not pretend to have any answers as to how to heal from these legacies, which must be a collective process, I hope my ongoing research into these institutions, including an oral history project in the planning stages, might contribute to this effort. For whatever we call them, and I am increasingly convinced that “boarding school” is much too gentle a word for them, I hope the inclusion of Hawaii in this report can bring greater awareness to both the damage these institutions wrought and the Hawaiian people’s resilience.