U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has found an insidious new way to work around the hard-fought “sanctuary” protections that hundreds of counties across the United States have adopted to prevent local law enforcement agencies from sharing data with its agents: a dizzying, privatized surveillance apparatus constructed by the database corporation LexisNexis.

ICE now has a specialized LexisNexis subscription that allows it to obtain private and public data without a warrant, without subpoenas and without requests to local police departments or sheriff’s offices.

For the bargain basement price of around $4.4 million a year, ICE agents buy access to vast reams of commercial and public data — 1.5 billion bankruptcy records, 77 million business contacts, 330 million unique cell phone numbers, 11.3 billion name and address combinations, 6.6 billion vehicle registrations and 6.5 billion property records, according to its website.

Through its partnership with LexisNexis, ICE now has access to “Accurint,” a research-and-locate tool tailored for government and law enforcement. This portal is being used by ICE agents in a bid to skirt sanctuary ordinances across the country.

Accurint’s “jail booking search” (part of the Accurint Virtual Crime Center) returns a nondescript webpage: A mugshot and a dossier of personal information — name, address, weight, height, citizenship status, Social Security number, employer, and more.

It’s not sleek (the site mostly contains simple black-and-white text fields), but the lackluster interface hides a pernicious, possibly illegal surveillance tool.

The scale of surveillance here is astounding. Accurint is a product of LexisNexis, one of the world’s largest commercial data brokers, which boasts access to more than “84 billion public records from over 10,000 disparate sources” — think driver’s licenses, court records, cell phone subscriptions, cable or electricity bills, arrest data, property records, and more — for its customers.

As part of a contract worth up to $22.1 million signed with LexisNexis in 2021, thousands of ICE agents can, with a few keystrokes, access real-time jail booking data, including incarceration status and release date, on millions of people across the country. The site is updated as often as every 15 minutes.

A Sprawling Surveillance Apparatus Created by LexisNexis

Accurint is just a small part of a sprawling surveillance apparatus that gives ICE agents access to one of the world’s largest troves of personal information: A vast database containing info on hundreds of millions of people that was handed over to ICE as part of the same LexisNexis contract. The data — which includes names, addresses, phone information, utility bills, arrest and release data, and so much more — is simply bought and sold, available to ICE as part of a tidy subscription package.

LexisNexis says it has 283 million active “LexIDs” in its database — its term for individual dossiers of personal information — meaning many tens of millions, if not hundreds of millions, of people are in its databases. And it’s not only the initial targets swept up in this digital dragnet: A single search can return information on multiple people, as noted by the company itself. LexisNexis says its database can “find connections” between the initial targets and “relatives and business associates.”

If you’re a target of surveillance by ICE, your friends, your family, your colleagues and your associates could all be surveilled as well — pulled into a massive, digital trawling effort by immigration enforcement that goes back to the Obama era and has involved multiple data broker contractors.

The very same law enforcement officials tasked with upholding the state’s various sanctuary ordinances also sat on the board of LexisNexis, the company contracted to skirt them.

LexisNexis signed this contract the same month as ICE’s previous data broker of choice, Thomson Reuters, saw its own ICE contract for these services expire. Since then, Thomson Reuters has come under increasing government and shareholder pressure. In December of last year, Sen. Ron Wyden successfully pushed for access to utility information to be cut from Thomson Reuters, and has continued pushing for the Consumer Protection Bureau to take further actions against data brokers. In April this year, Thomson Reuters announced it would review its ICE contracts for potential human rights violations, possibly ending its work with ICE, in response to shareholder pressure generated as part of our #NoTechforICE campaign.

In documents unearthed via Freedom of Information Act requests, the immigration justice groups Mijente and Just Futures Law showed that ICE agents searched LexisNexis more than 1.2 million times over just seven months (between March 2021 and September 2021) — and that hundreds of thousands of searches were conducted by Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO), the division of ICE responsible for deportations.

Worse, this data is now being used as a backdoor to skirt sanctuary ordinances across the country — ICE is now often able to access the data it seeks through this privatized database even in cities and states that have hard-fought laws to prevent local law enforcement from cooperating with ICE agents on deportations.

These sanctuary protections, a legacy of years-long immigration organizing that became particularly urgent under Trump, are being purposefully undermined by ICE.

In a government contracting document shared by Mijente and Just Futures Law, ICE’s stated rationale for contracting with LexisNexis was the “increase in the number of law enforcement agencies and state or local governments” that limited data sharing with ICE as part of sanctuary ordinances.

In hundreds of jurisdictions where laws prevent local law enforcement from helping ICE with its deportations by informing agents when someone is released from jail, for instance, the agency can simply buy this data directly from third parties like LexisNexis. ICE no longer has to rely on local police officers or sheriff’s deputies to tell them when certain people are being released from jail, when they have a parole hearing, or when they’ll next be at the courthouse. ICE has this data directly and can send its agents to pick people up, arrest them and ultimately deport them.

Avenues for Resistance

But cities and counties are fighting back. In Chicagoland on Wednesday, Cook County Commissioner Alma E. Anaya is holding a public hearing investigating whether the county’s contract with LexisNexis and ICE’s contracts with data brokers may violate the county’s sanctuary ordinance. The ICE Chicago field office conducted more than 13,000 searches in the seven-month period covered by our FOIAs — the most of any city in the country except San Diego.

In 2024, the presidential administration may well change. If it does, its immigration agents will have a turnkey-ready surveillance system to target millions of people across the country.

The hearing — the first time that a legislator will investigate ICE’s use of data brokers to skirt sanctuary protections — was prompted by the #NoTechforICE campaign’s recent research report detailing how LexisNexis is used by ICE in Colorado to skirt the state’s sanctuary laws. The report’s findings suggested that ICE is engaging in this practice across the country.

Advocates with the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition (CIRC) have been organizing in their state, too. Our joint report with CIRC uncovered massive conflicts of interest whereby the very same law enforcement officials tasked with upholding the state’s various sanctuary ordinances also sat on the board of LexisNexis, the company contracted to skirt them. Since then, the group has been meeting with sheriffs and pushing Colorado legislators to update the state’s sanctuary policies to prevent the kind of workarounds that ICE is exploiting in Illinois.

And the librarian and legal communities are fighting back too. LexisNexis and its largest competitors, like Thomson Reuters, are used widely by the research, legal and journalism community: academics, librarians, lawyers, journalists, and others all scour LexisNexis databases to find sources, case files, news articles, and more.

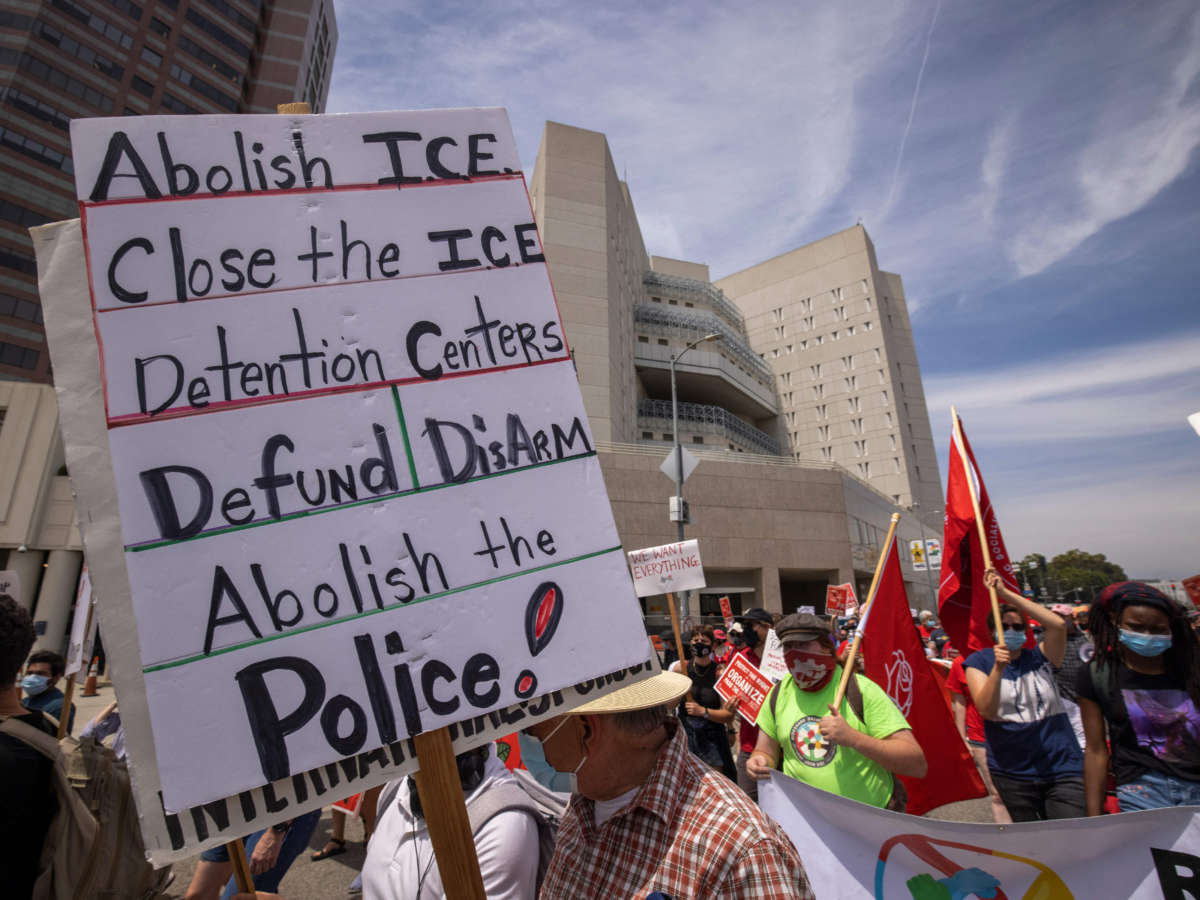

These same communities have been calling out the companies on their ICE contracts: In just the last month, librarians and advocates have protested outside the American Librarian Association’s annual conference in Washington, D.C., and the American Association of Law Libraries annual conference in Denver, demanding that LexisNexis cut its contracts with ICE. More than 2,500 librarians, law students, scholars and legal professionals have signed Mijente’s petition urging LexisNexis to stop working with ICE, part of the #NoTechforICE campaign we at Mijente have been leading since 2018.

That campaign has pulled together students, tech workers, abolitionists, academics, librarians, lawyers, shareholders, and a variety of others who oppose ICE and Silicon Valley’s collaboration with deportation forces, targeting the contracts that Silicon Valley firms like Palantir and Anduril have with ICE or Customs and Border Protection (CBP). We have mobilized hundreds-strong protests outside tech company headquarters, organized shareholder resolutions at leading tech companies, published in-depth research reports, and once brought a cage to Burning Man in a bid to stop the anti-immigrant work done at these tech firms.

This surveillance, powered by LexisNexis, is a danger to all immigrant communities. Regardless of who occupies the White House, ICE has a mandate to detain and deport every undocumented person in this country, a mandate it follows under Democrats and Republicans alike. And these surveillance contracts are signed for years at a time, outlasting the policies of any one administration.

In 2024, the presidential administration may well change. If it does, its immigration agents will have a turnkey-ready surveillance system to target millions of people across the country.

ICE’s attempts to find a data workaround to sanctuary city laws is a natural consequence of this single-minded focus on deportations — regardless of the surveillance required and regardless of the legal protections in place.

Sanctuary cities and counties, librarians and lawyers, and even the workers at these data broker companies themselves must resist as one and organize against these contracts. It’s the only way we can ensure a surveillance-free future for immigrants in this country.