Three weeks before the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) would calmly confirm massive racial disparities in a nationwide database tracking fatal drug overdoses, a team of researchers working under a federal grant program published a groundbreaking study concluding that “traditional” encounters with police do little to prevent drug-related crime. In fact, the study found these encounters increase the likelihood that at-risk people will overdose and die in the future.

Focusing on Madison, Wisconsin, a mid-size city where policing practices shifted roughly five years ago in response to the overdose crisis, the study found that people at risk for overdose were more likely to die that way if they were arrested by police for drug-related crimes and pushed into the criminal legal system. Arresting and jailing people did not reduce recidivism and was associated with longer stays in jail. Incarceration is known to drastically increase the risk of a drug overdose, especially among opioid users. Identified anonymously through public criminal legal records, a number of the people tracked by the study did not survive.

The study, published the Journal of Harm Reduction, did not make many headlines, even after the CDC released its latest alarming report on fatal overdoses last week. According to the data, drug-related fatalities increased by 30 percent across 25 states from 2019 to 2020. The rise of the COVID-19 pandemic stirred global chaos in early 2020, and by then the Trump administration’s approach to containing the overdose crisis was failing. Overdose deaths among white people grew by 22 percent after slowing in recent years. Overdose deaths among Black and Indigenous Americans exploded at roughly twice that rate — an increase of 44 percent and 39 percent, respectively.

Black men under the age of 65 died of drug overdose at a rate seven times higher than white men over the time same period. When considered alongside the Madison study and research on “double standards” in drug policing, the CDC data suggests Black and Indigenous people were less likely to access addiction treatment and more likely to encounter police. Other “social determinants” such as income inequality exacerbate the racial disparities in overdose death, according to the CDC.

Policymakers spent billions of dollars over the past decade to expand addiction and mental health services in response to the overdose crisis, but the results are anything but equal. Notably, racial disparities in overdose deaths were higher in counties with rising income inequality — including in areas where addiction treatment options are now more widely available. A recent National Institutes of Health study examining four states hard-hit by the crisis found that fatal overdoses among Black people increased by 38 percent between 2018 and 2019, but there was little change among white people and other groups.

Then COVID hit, isolating drug users from friends, family and health care services, all of which can reduce the risk of overdose. The CDC recorded 91,799 overdose deaths in 2020, and by April 2021, the number of estimated deaths for that year surpassed a record 100,000. The COVID pandemic widened existing racial gaps in health care and addiction treatment, according to Mbabazi Kariisa, a health scientist at the CDC’s Division of Overdose Prevention.

“Most people who died by overdose had no evidence of ever getting treatment before their death,” Kariisa told reporters last week.

Medical racism in pain and addiction care is widespread and well documented, but health care disparities only tell part of the story. Simply put, Black, Indigenous and low-income people continue to be disproportionately targeted by police and punished for using drugs rather than receiving support and medical care.

The deadly results of drug policing are an uncomfortable reality for President Joe Biden, who recently called on Congress to provide funding for hiring 100,000 additional police officers nationwide after months of Republicans accusing Democrats of being soft on crime.

The Biden administration is doubling down on law enforcement and interdiction, which have consistently failed to make a meaningful dent in the illicit drug supply.

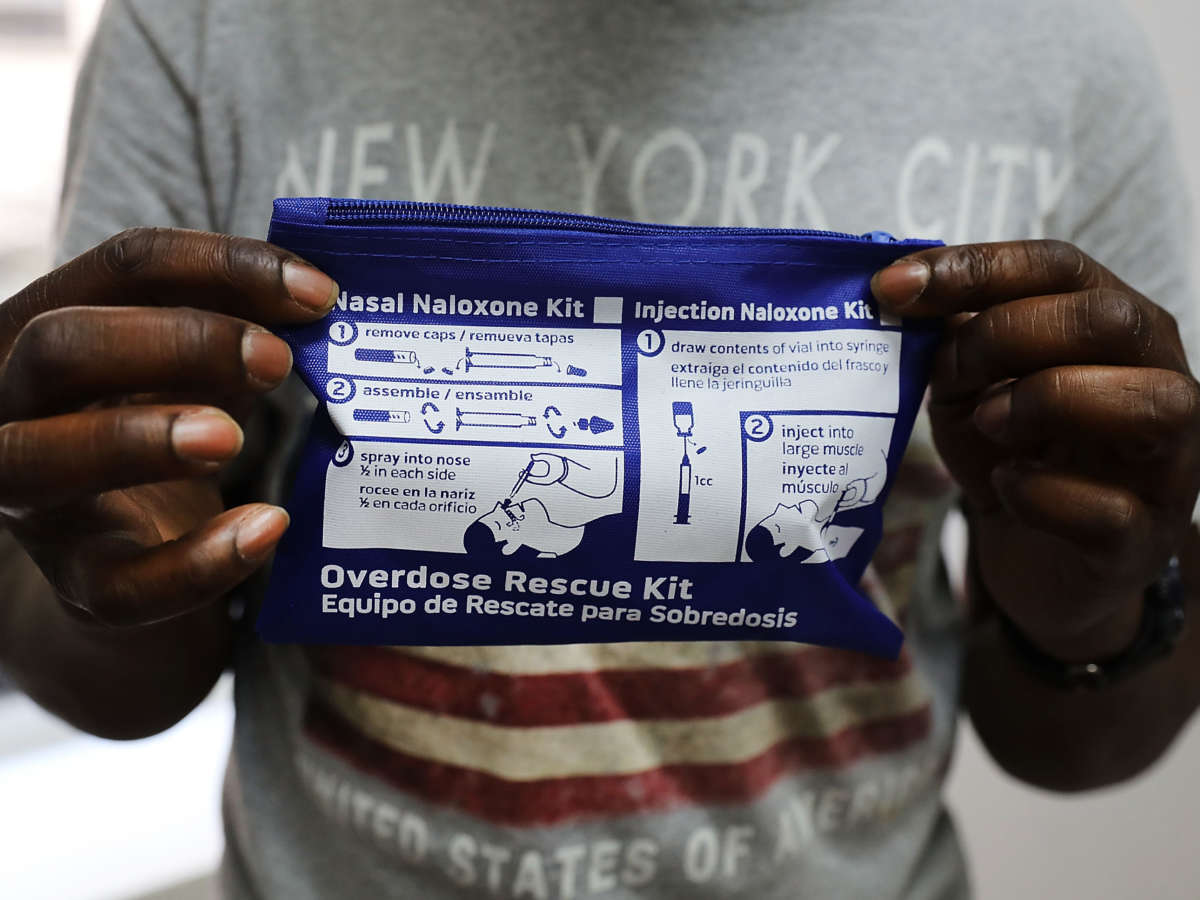

Even as it pursues these failed strategies, the administration is simultaneously allocating more resources to health supports for drug users. Despite right-wing backlash, the federal government is finally funding harm reduction services such as syringe exchange programs and naloxone distribution that help people stay healthy and provide pathways to addiction treatment.

Debra E. Houry, director of injury prevention at the CDC, said increasing access to harm reduction services is crucial for preventing overdose deaths, especially in underserved Black and Indigenous communities. Federal agencies’ support for harm reduction is a big change, and it comes thanks to decades of grassroots organizing. However, activists worry it’s too little, too late. Harm reduction organizers see drug decriminalization as a major strategy for reducing harm. Yet CDC officials did not provide a clear answer when asked if the decriminalization of small amounts of drugs should be a public health priority given the scale of the overdose crisis.

The study found that people at risk for overdose were more likely to die that way if they were arrested by police for drug-related crimes and pushed into the criminal legal system.

Houry suggested that health officials are training federal drug police to respond to overdoses, avoid reinforcing harmful stigmas associated with drug use and guide people at risk toward addiction treatment. However, harm reduction activists say marginalized drug users cannot trust police and hide from them instead of seeking help, since the drugs they use are still illegal. Police have never been effective emergency health care responders; their primary jobs regarding drugs are to invade houses, flip informants, investigate, seize drugs and make arrests. As long as drugs remain illegal, drug users know police have the power to seriously disrupt their lives.

In Madison, where researchers collected data on drug-related arrests and overdose events, city and police officials launched a “diversion” program in 2017 that allows for the partial decriminalization of drugs for people at risk of overdose. Under the program, people who overdose or are stopped for “victimless,” drug-related offenses are referred to an addiction treatment program as an alternative to jail. The researchers concluded that people who were at risk for overdose and encountered police before the diversion program were more likely to be rearrested, spend time in jail for longer periods, and eventually suffer a fatal overdose compared to people who encountered police after the program was in effect.

“Overall, our results document an individual’s increasing struggles with addiction as we observed increasing trends with arrest, incarceration, and overdose events following overdose-related police contact under the criminal justice-based policing method,” the authors wrote.

Making the shift away from punishing drug users and toward decriminalization, harm reduction and better treatment will not be a simple process. In Oregon, where voters decriminalized small drug possession in 2020, state officials struggled to quickly funnel millions of dollars of funding for expanding addiction treatment from the state’s legal cannabis revenues as the pandemic-fueled overdose wave swept the nation. Policymakers must remain committed to addressing drug use with public health strategies instead of criminalization, advocates say — but so far, Democrats in Washington are unwilling to take a stand.