Amid an unprecedented public outcry and the threat of market meltdown, the U.K.’s new government has been forced into a humiliating U-Turn, reversing the huge package of tax cuts it recently announced to benefit the wealthiest 1 percent of income earners.

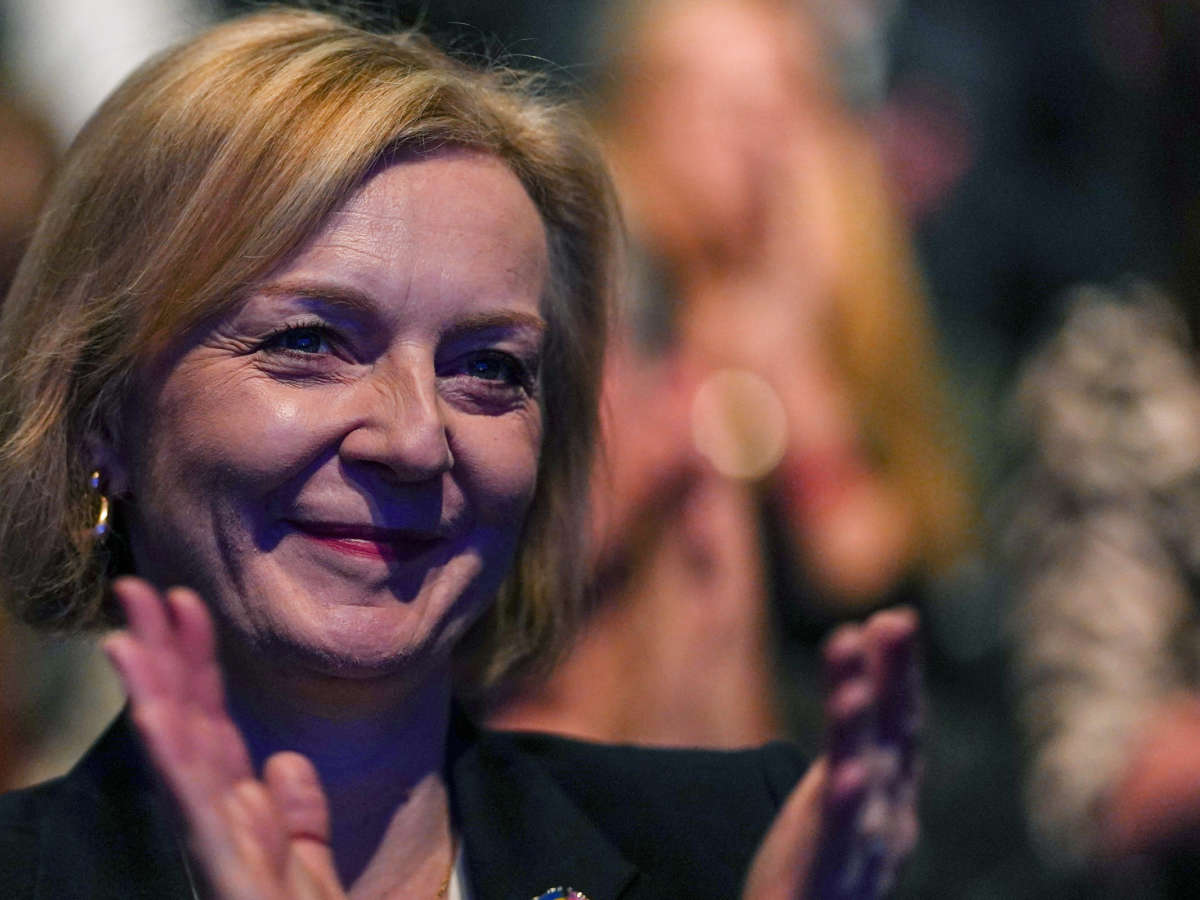

The government — led by Prime Minister Liz Truss and following economic policy shaped by Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng — had announced the tax cuts a little over a week ago, on September 23. This surely must rank as one of the quickest and most politically devastating reversals of a centerpiece government policy in U.K. history.

The Truss-Kwarteng package that plunged the UK’s economy and political system into crisis, and which was not subject to the rigorous scrutiny applied to full-blown budgets, had abolished the top rate of tax for high earners. Backed by government borrowing, it was promoted as the biggest tax-cutting package in Britain in a half century. Meanwhile Kwarteng and Truss announced that the package was merely a precursor to still more tax giveaways to the wealthy amid their zealous push for a low-tax, low-regulation, low-social safety net model for the Brexit-era economy.

The tax cuts were to the tune of £45 billion. But any benefit to the country’s economy that might have been followed from this giveaway was instantly obliterated by the vast economic damage unleashed by it.

Last week, the markets responded to Kwarteng’s mini-budget by melting down, and the British currency plunged, at one point looking like it would crash below parity with the U.S. dollar. The Bank of England was forced to announce that it would, if necessary, embark on “shock-and-awe” interest rate increases in order to protect the pound, and it then had to commence a £65 billion bond-buying spree to preserve the liquidity of pension funds and other big institutional investors. For a few hours, it looked like the entire pension-investment system in the U.K., worth trillions of pounds, was in crisis, a disastrous outcome that could conceivably have triggered the sort of cascading global financial crisis that unfolded when the U.S. financial system collapsed 14 years ago.

Tens of billions of pounds of value were wiped out of government bond investments overnight; and those traveling overseas suddenly found that their vaunted British pounds went a whole lot less far in late September than they had gone a month earlier. At its nadir, the value of the pound fell to the equivalent of $1.03 in U.S. currency, and it looked for a moment like it would soon end up worth less than the U.S. dollar, a massive national humiliation that, had it occurred, could have brought down Truss’s government just three weeks after it was formed. As it was, even with the vast Bank of England intervention, the pound finished the week at near all-time lows, worth only $1.11, roughly 20 percent lower than it was just a year ago.

So uncertain was the mortgage market about Britain’s financial future and the price of borrowing over the coming months that some of the country’s biggest lenders suspended the issuing of new mortgages in the middle of last week, and many borrowers found themselves stranded midway through the process of securing their home loans.

The markets responded to Kwarteng’s mini-budget by melting down, and the British currency plunged.

The Bank of England has told Kwarteng that the country is already in a recession. And, in the wake of the mini-budget, and the havoc unleashed in U.K. markets, things are likely to get a whole lot uglier in the coming months. Analysts are now predicting a housing market crash in the U.K. as borrowing costs soar. For unlike in the U.S., where most mortgages are now fixed-rate 30-year loans, in Britain, most mortgages are short-term, either needing to be refinanced after two or five years, or, for nearly a million mortgage holders, based around entirely adjustable rates. As a result, the U.K.’s housing market, and those with mortgages, are particularly vulnerable to rapid shifts in the cost of borrowing.

As all of this unfolded, the International Monetary Fund issued a warning, of the kind it more often issues to deeply corrupt, insolvent nations, that the government’s moves were both inflationary — pumping far too much money into the economy just at a moment when there is an internationally coordinated effort to rein in inflation by tightening up on monetary policy — and likely to fuel rampant economic inequality.

The Financial Times ran a chart detailing that, out of 275 political parties spread over more than 60 countries that secured at least 5 percent of the vote in recent elections, Truss’s government was pursuing the most right-wing economic policy on Earth. On a scale of 1 to 10, based on a series of economic policy metrics, it awarded the U.S. Republican Party just over 8 — about where the Brothers of Italy, the new neofascist government of Italy, were on the scale – and Brazilian far right leader Jair Bolsonaro’s Social Liberals a 9. Truss’s Conservatives, in the U.K., ended up at 9.5, about as right-wing economically as the Financial Times’s analysts say it is possible to be, and far to the right of where Boris Johnson’s government was prior to Johnson’s political demise.

The Washington Post prominently ran an opinion piece denouncing Truss’s government as “bonkers.” El Español, in Spain, blared the news that, “The UK Seems To Have Imploded.” And across Europe, newspapers, already furious at the U.K.’s Brexit theatrics, have fallen over themselves lambasting Truss’s stewardship of the economy.

Meanwhile, the Conservative Party’s support continues to erode, and the U.K. government’s crisis of legitimacy accelerates. Recent polls had showed that the Labour Party, led by Sir Keir Starmer, was 17 points ahead of the Conservatives. By the end of last week, a YouGov poll had Labour up by a stunning 33 percent, one of the largest leads ever posted in the history of polling in the U.K. Barely one in five voters polled said they would be voting Conservative in the next election.

The imploding markets pulled back the curtain on Truss and her team. If the latest polls are any indication, the British public was absolutely repelled by what they saw.

It’s hard to imagine a more inept opening act than that put on by Truss and her team of right-wing zealots over the past few weeks. Truss was chosen not by the electorate at large, but by a vote held among the 160,000 members of the British Conservative Party. She is the third leader of the Conservative Party in as many years and, having not led her political party to victory in a general election, her personal mandate is minimal at best.

In ascending to the premiership, Truss has shown a penchant for modeling herself on the Iron Lady, Margaret Thatcher. Instead, now that she is in power, she is looking far more like the Wizard of Oz. She talks the big talk, but at the end of the day, it’s all smoke and mirrors. Last week the imploding markets pulled back the curtain on Truss and her team. If the latest polls are any indication, the British public was absolutely repelled by what they saw.

It’s unlikely that Truss and Kwarteng’s humiliating policy retreat today, backpedaling on a tax cut that only a few days ago they had said was vital to the future growth of the U.K. economy, will appease the infuriated British electorate. If anything, it will only make Truss and Kwarteng look more inept and their stewardship of the U.K.’s economy look even more haphazard.