Tracing the contours of the Hollywood Hills, Los Angeles’s District 13 cuts an asymmetrical patch from the heart of the Southern California metropolis. The district comprises a region that includes, among other notable areas, Silver Lake, Echo Park, Hollywood, Los Feliz, Little Armenia, Thai Town, Koreatown and Filipinotown. One of Los Angeles’s most liberal districts and home to some of the city’s most desirable real estate, District 13 and its wealthy homeowning constituents coexist with a population of working-class renters and homeless people, who face the brunt of the injustices that are the hallmark of U.S. inequality.

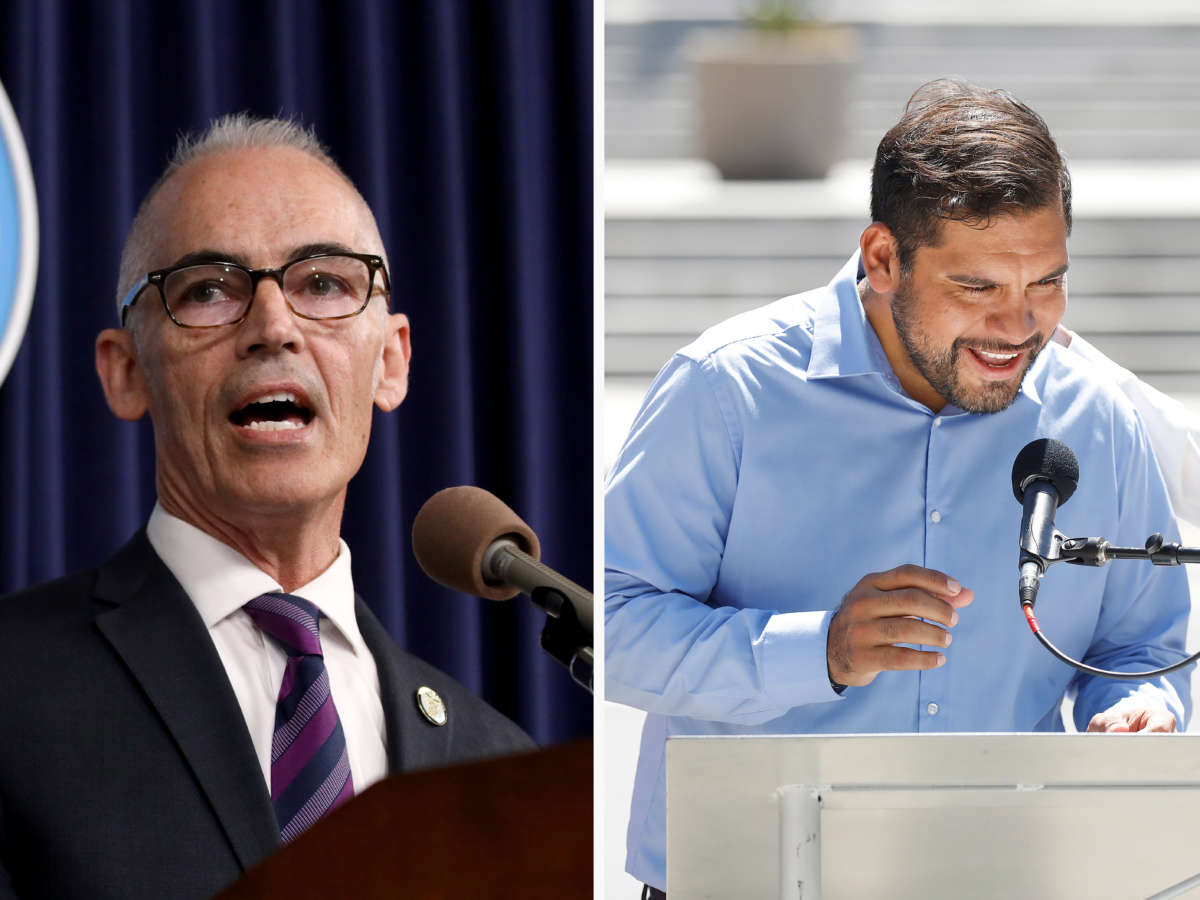

On November 8, District 13’s residents will vote to determine their next city council representative, a seat currently occupied by two-term incumbent Mitch O’Farrell. A city hall insider for two decades, O’Farrell served in now-Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office and has spent the last decade as the district’s elected council member. (As a result of a late-game shake-up — the resignation of Council President Nury Martinez over a leaked call recording that captured her and other leaders’ stunningly racist comments — O’Farrell is acting as president pro tempore of the council.)

Challenging O’Farrell is longtime union leader, organizer and Democratic Socialists of America member Hugo Soto-Martinez. Soto-Martinez’s victory in the summer primary saw him come away with a decisive lead: 40.63 percent of the vote to O’Farrell’s 31.65 percent, carrying him to the runoff election in November.

In its broad strokes, this race’s narrative is, by now, a familiar one. Two candidates — an entrenched corporate liberal and a radical leftist upstart — will spar over their diagnoses and prescriptions for an untenable status quo of unaffordable housing, poverty, homelessness and brutal policing, to name a few of the contest’s most salient issues.

Radicalizing Experiences

For many Angelenos, particularly working-class people of color, life in the city is often beset by devastating disparities: impossible rent hikes, rampant gentrification and displacement, and the flourishing of homelessness — a homegrown humanitarian catastrophe that is especially pronounced in Los Angeles, if hardly unique to it.

Soto-Martinez says that during his time in organized labor and other movement work (he has been engaged with community groups, the Los Feliz Neighborhood Council, NOlympics LA, efforts to defeat Sheriff Joe Arpaio, and many more initiatives over the years), he witnessed a litany of everyday struggles faced by average people, an experience which, he says, has underscored the dire necessity of radical change.

Soto-Martinez was born in South Central to immigrant parents. His early experiences with police harassment and the criminal justice system, as well as his father’s disability, proved formative, as did his first encounter with collective organizing. In 2006, a union drive began at the hotel where he was a low-waged employee.

As he told Truthout, “I was still in college at the time — I got involved as a student and as a worker. We won the union, and I started working for them shortly thereafter. I’ve been an organizer with UNITE HERE Local 11 for the last 16 years.”

In his capacity as an organizer, he says he has worked closely with “the most vulnerable groups of people in the city — folks that make minimum wage and have no health insurance, that live in a one-bedroom apartment with multiple people…. They’re one paycheck away from being homeless. Most are immigrants, a lot of them are undocumented. I’ve been in the service of that community for my entire adult life.”

As a member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA’s Los Angeles chapter is the core volunteer engine of his campaign), Soto-Martinez does not dissimulate about his radical aims; he identifies organized collective struggle as a prerequisite for change.

“I’m very much viewing this [campaign] as an extension of the labor movement,” he said. “The labor movement does amazing work, and we should be proud of that — but many times, it’s just not enough. I’m trying to bring the same energy, the same level of agitation that we work with when unionizing workplaces, and do that on a large scale.”

Los Angeles operates under a “weak mayor” system, unusual for a city of its size. In the few municipalities that employ this governance structure, mayoral powers are less consolidated. Entities like the school board and metro board retain some independence from mayoral oversight. Los Angeles’s more empowered council is, then, responsible for planning, land use and infrastructure decisions — meaning “the city government and City Council can have a large role in addressing people’s actual needs,” Soto-Martinez explains. “We’re just trying to extend that.”

Housing is perhaps the keystone issue in this race, and in the city writ large. With nearly 60 percent of Los Angeles metro area renters spending more than 30 percent of their income on rent, according to a Harvard study, chronically inaccessible and unaffordable housing catalyzes a whole host of other social maladies.

“Right now, we’re simply not building enough affordable housing that essential workers can afford,” Soto-Martinez said, with perceptible frustration. “We build market-rate and luxury developments, but there’s no point in building it if people can’t afford to live in it.”

An Entrenched Incumbent

Soto-Martinez’s opponent, incumbent Council member Mitch O’Farrell, has 20 years of experience in Los Angeles government and has presided over District 13 for a decade. Also from working-class roots, O’Farrell is a member of the LGBTQ+ community and is of Native ancestry. O’Farrell’s campaign points to a series of successes and results realized during his terms: a minimum wage increase, COVID-19 relief measures and a carbon-neutrality plan are all among his touted initiatives. He has spoken out for LGBTQ+ rights and the recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ Day over Columbus Day, and notes his support for plenty of progressive touchstones.

At a glance, it would seem that O’Farrell and Soto-Martinez are much in alignment on core issues and values. However, a deeper look at O’Farrell’s policy record and funding sources, critics charge, will belie his close ties with profit-focused development interests. Critiques from the left have flagged O’Farrell’s support for measures that criminalize camping and the street activities of the unhoused, turning to punishment and policing to sweep encampments, “beautify” neighborhoods, and ultimately facilitate gentrification and real estate profit. His policies have earned him the ire of tenant activists, who have long accused him of doing too little to help secure affordable housing and halt displacement. And, tellingly, campaign finance records from the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission point to O’Farrell’s acceptance of donations from developers and landlords, fossil fuels, tech and venture capital, as well as known corrupt officials, lobbyists, power brokers and other dubious sources.

O’Farrell is not a sworn enemy of affordable housing. His city website states that during his tenure, “the 13th District has seen more than 4,000 units of affordable and permanent supportive housing built, approved, financed or under construction, representing 29% of the approximately 15,000 new housing units in that timeframe.” It also touts a 23 percent decrease in homelessness in the district, representing around 1,000 people, which is attributed to O’Farrell’s efforts to provide housing and services. (An outside review of the data by CityWatch LA suggests that that the number of affordable units that O’Farrell can reasonably take credit for may be lower. And, while units may have been added, at the same time, “According to data from the Los Angeles Housing Department, 1,691 rent-stabilized apartments were removed from the market in CD 13 between 2014 and 2020,” under the infamous Ellis Act.)

But moves like O’Farrell’s rhetorical advocacy and lauding of affordable housing have taken place alongside other decisions — like supporting rent-stabilized apartments being used as Airbnbs and opposing the broadening of a pandemic eviction moratorium, generating criticism from tenant activists. On the whole, O’Farrell has sought to provision affordable housing by, as he described it in a 2021 interview with The Planning Report, prioritizing construction by investment and development interests. Some of the units in these developments can be allotted for affordable spaces, negotiations permitting. He emphasized his willingness to fight for affordability and angle for the allocation of affordable units in “project after project.”

Soto-Martinez, for his part, says having it both ways — both mollifying corporate developers and serving low-income tenants — is not really possible. “[O’Farrell] represents the people who are profiting off the city,” the candidate said. “When we think about the suffering or the resources that people don’t have — that comes at a cost. Somebody is winning when that person’s losing. And the people that are winning in the city are the developers, the real estate industry and the police union (45% of our discretionary funds go to the police budget).”

The Infamous Echo Park Lake Sweep

In March 2021, the inherent violence of the state’s response to homelessness came to the fore during the sweep of a large unhoused encampment in District 13’s Echo Park Lake. O’Farrell, who had made repeated attempts to order sweeps of the camp, eventually found himself defending the results of the large-scale removal — during which 182 protesters, journalists and legal observers were arrested by 400 militarized LAPD officers, as the camp’s unhoused population was battered and banished. The violent spectacle drew national attention and condemnation.

City assurances that residents would be connected with housing proved hollow. By October 2021, only four of those removed from the encampment had found permanent housing. Many of those initially placed in interim housing had returned to the streets or disappeared; several were dead.

Soto-Martinez has leveled heavy criticism at Council member O’Farrell for what the former sees as the latter’s role in precipitating the crisis, charging that O’Farrell is “an architect of criminalizing the homeless in the City of Los Angeles. He was one of the first people to come out in favor of criminalization.”

Soto-Martinez was referencing O’Farrell’s early support for Municipal Code 41.18, a “sit/lie” law that criminalized the presence of the unhoused. O’Farrell also supported other criminalization measures, further camping restrictions, bans on providing free meals, RV parking and other “quality-of-life” strictures. More broadly, O’Farrell regularly calls for raising police budgets, and he has helped facilitate evictions and the displacement of working-class housing for upscale development while backing poverty criminalization efforts that serve as “weapons of gentrification,” as Jonny Coleman put it for Knock LA.

O’Farrell’s campaign office did not respond to repeated requests for comment by time of publication.

Further criticism came from a video posted by Soto-Martinez, in which he relates how O’Farrell approved a luxury development that demolished the beloved Amoeba Records right after developer GPI Real Estate Management sent donations to his office’s coffers. These sorts of claims of undue influence by Soto-Martinez and other critics are buoyed by the fact that O’Farrell enjoys the passionate support of the real estate lobby: the California Apartment Association PAC, the Building Owners & Managers Association of Greater Los Angeles PAC and the Central City East Association, among others. During the primary, real estate interests spent $1.1 million on independent campaigns and pro-O’Farrell messaging (on top of paying for all manner of attack ads against Soto-Martinez).

O’Farrell has been able to tout a considerable fundraising intake, both up to his loss in the summer’s primary and to date. He has raked in numerous maxed-out donations from wealthy individuals and corporate political action committees. (In the last city council election, development interests were practically falling over themselves to help elect O’Farrell; one real estate investor violated donor limits using shell companies and was hit with a $17,000 fine.)

Meanwhile, as the Soto-Martinez campaign is keen to highlight, nearly all contributions to the upstart effort have come from small individual donors. Seventy-seven percent of Soto-Martinez’s contributions were under $100, to a sole 1 percent of O’Farrell’s. Yet despite this disproportionality, Soto-Martinez still outraised his opponent in the primary, indicating the extent of his grassroots support.

“People are very upset at the status quo,” he said. “They’re inspired by what we’re talking about — I think that’s resonating very well…. People are gravitating toward the vision that we have for the city.”

Mobilized and Galvanized Campaigners

Frances Gill is a longtime DSA organizer, a Service Employees International Union-represented nurse and an enthusiastic volunteer for Hugo for District 13.

“When I’m knocking doors,” Gill told Truthout, “one of the first questions that I ask somebody is, ‘If you could change one thing in the neighborhood, what would you change?’ Everybody says housing. Everybody says rent. Everybody says homelessness.”

Gill added: “People see the luxury developments going up in the district, and they know that’s the reason that rent is expensive.” Housing is “totally unaffordable to the vast majority of people in the district. People see that with their own eyes, and then they feel it in their pocketbooks.”

Gill and other energetic organizers, many of them with DSA, have cited the sense of solidarity and empowerment that they have found in door-knocking and agitating for Soto-Martinez.

For its support, O’Farrell’s campaign has been able to count on the endorsement of Los Angeles Democratic Party related political organizations, LGBTQ+ groups, a number of major unions, Planned Parenthood, and several chambers of commerce and business PACs. While his campaign is not an especially grassroots operation, his backers have fielded an Independent Expenditure Committee that is unconvincingly attempting to at least resemble one.

“Neighbors United to Re-elect Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell” is a project of, its website reads, “our neighbors, community leaders, small business owners and others.” (A disclosure then lists the “BizFed PAC, a Project of the LA County Business Federation” and J&J Hollywood, LLC, a real estate interest, as major funders.)

A Contestation Over Housing Rights

It is clear that for many the race between Soto-Martinez and O’Farrell has become a kind of referendum on moral and ideological approaches toward housing issues and the criminalization of the unhoused. Soto-Martinez’s platform proposes bolstering housing and social programs; one idea, for instance, is to convert unused spaces — motels, commercial spaces, offices — into affordable or free housing. Other planks include creating new union jobs for street outreach workers and deploying unarmed crisis teams instead of cops.

On housing, O’Farrell has sought more of a middle way, allowing for profit-seeking investment and appeasing development interests while negotiating for a percentage of affordable unit allocations. O’Farrell has publicly stated a belief in the necessity of housing-first remedies, telling The Planning Report, “I have simply focused on comprehensive housing solutions, including covenanted affordable housing, tiny home villages, the first safe sleep site managed by the City, and safe parking sites.” The fundamental clash in this race is between a radical, socialist vision of major systemic reform — in other words, meeting the housing challenge with an approach that is as drastic as the crisis — and a program of measured and technocratic proposals that utilize existing structures.

For O’Farrell, the liberal approach has, critics say, consisted of policing the unhoused, negotiating with real estate capital and furthering half-measures like tiny homes, sleep sites and other forms of sanctioned encampments. Writing in Knock LA, Ryan Coleman bluntly summarized much of the criticism of O’Farrell that has been issued from the left: “During his tenure as councilmember, O’Farrell has eviscerated tenants’ rights, attacked the livelihoods of street vendors, accelerated the frequency and brutality with which homeless sweeps are conducted, made it harder for homeless people to receive free meals, prioritized wealthy donors over average constituents, and supported unconstitutional policing practices.”

Soto-Martinez’s bid comes amid a summer of victories for the left in Los Angeles, as well as the first dethroning of a Los Angeles incumbent in 17 years by Nithya Raman. But, although Soto-Martinez showed a strong lead in the primary, the DSA member’s momentum could prove tenuous — in no small part because O’Farrell enjoys considerable support from many constituents, along with powerful interests and other elements in City Hall.

That much was clear when, in another twist in what has become a remarkable “October surprise,” the same set of leaks that led to the ignominious downfall of Council President Nury Martinez surfaced another recording. This tape captured a conversation in which council members can be heard disparaging Soto-Martinez and his organizing record. They then discuss how to “protect Mitch” and keep Soto-Martinez from power — even alluding to a “deal” of a job offer to dissuade him from the candidacy.

As early voting begins this week, the urgency of the issues at hand in this race will only intensify. The staggering homelessness crisis is traceable to the dire need for affordable housing; both candidates have, at least rhetorically, found common ground on that point. But their prescriptions diverge, with Soto-Martinez’s vision of transformative change contrasting with O’Farrell’s piecemeal solutions and negotiated compromises with business. As such, O’Farrell will certainly continue to receive sharp criticism for his corporate funders, and for working shoulder-to-shoulder, and sometimes hand in hand, with Los Angeles’s bastions of profit.

Though these two candidates are facing off in a race that is small relative to the scale of national politics, their clashing ideologies stand in for a nationwide patterns, and the degree to which “progressive” ideology has become bifurcated between leftists and liberals. The campaigns of socialist candidates across the country have thrown these divisions into relief.

The maladies that are so visible in Los Angeles are also ubiquitous across the United States, and they will continue to fester in the absence of transformative interventions at the systems level.

More radical solutions like those of Soto-Martinez may well prove to have increasing purchase as austerity, threadbare social services, unaffordable housing and other pathologies of the neoliberal era continue to visit their grim toll on people of color and the working class.

Should this be attributed to Soto-Martinez? If so, I think we can cut the direct quote above and just use this paraphrase.