At the United Nations this week, President Joe Biden sought to distance his administration from the Trump administration’s attacks on climate policy. Biden announced that the United States will double its contribution to international climate finance to $11.4 billion annually by 2024 under the Paris Agreement to help poorer nations reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate disruption.

But Indigenous and climate justice activists largely characterized the new pledge as falling far short of what is needed to truly address the ongoing climate disaster. They are also calling on Biden to appoint climate leaders as financial regulators, and separately, to stop Trump-approved pipelines including the Dakota Access Pipeline and Canadian oil giant Enbridge’s Line 3 tar sands pipeline.

“President Biden is attempting to turn the page from the Trump administration, but until he uses his authority to stop all Trump-era fossil fuel projects, our communities will continue to raise the red flag,” said Joye Braun, national pipelines organizer for Indigenous Environmental Network, in a statement.

Biden’s pledge comes as a new UN report on global emissions targets found that the planet is still on track to warm 2.7 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100 — far above the 1.5 degrees that scientists and the Paris Agreement established the world should be targeting, and as Arctic sea ice has reached its annual low, the 12th lowest on record.

Congressional progressives including Sen. Chris Van Hollen and Representatives Jamaal Bowman and Ilhan Omar are using the moment to pressure Congress and Biden, calling on them this week to support the Polluters Pay Climate Fund Act, or “Make Polluters Pay” bill, and to incorporate the bill as part of Biden’s $3.5 trillion reconciliation package.

The bill would require companies like ExxonMobil, Chevron and other major climate polluters to pay a combined $500 billion at minimum into the Polluters Pay Climate Fund based on their respective percentage of global emissions. The money would be dedicated to helping vulnerable and marginalized communities adapt to climate impacts, transition to renewable energy and advance environmental justice.

“I’ve witnessed my district and community be devastated by recent storms and climate impacts that were the direct result of global emissions from major fossil fuel companies like Exxon, Shell, and Chevron,” said Rep. Jamaal Bowman this week. “Polluters must take full responsibility for their destruction and pay up now.”

“Polluters must take full responsibility for their destruction and pay up now.” —Rep. Jamaal Bowman

The lawmakers called the legislation a straightforward way to generate revenue for President Biden’s “Build Back Better” agenda, calling on him not cut the reconciliation bill without first adopting their “polluters pay” approach. Still, leading climate activists have noted that the bill would only account for a fraction of the fossil fuel industry’s damages while allowing the industry to continue to pollute.

Meanwhile, climate activists are also ramping up a pressure campaign demanding major Wall Street banks stop financing fossil fuels by the start of the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland, on November 1. Among COP26’s major goals are global emission reductions of about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, and $100 billion in annual financial aid from rich to poor countries — with half of that going to poor nations to help adapt to climate disruption’s worst impacts.

Climate activists say the U.S. won’t be able to meet its emissions targets or climate finance goals, however, unless financial regulators force banks, insurers and asset managers to stop financing fossil fuels. With the Biden administration set to release its climate-related financial risk strategy, climate campaigners are renewing calls for President Biden to appoint a progressive climate leader to head the Federal Reserve and staging direct actions outside major fossil fuel financers.

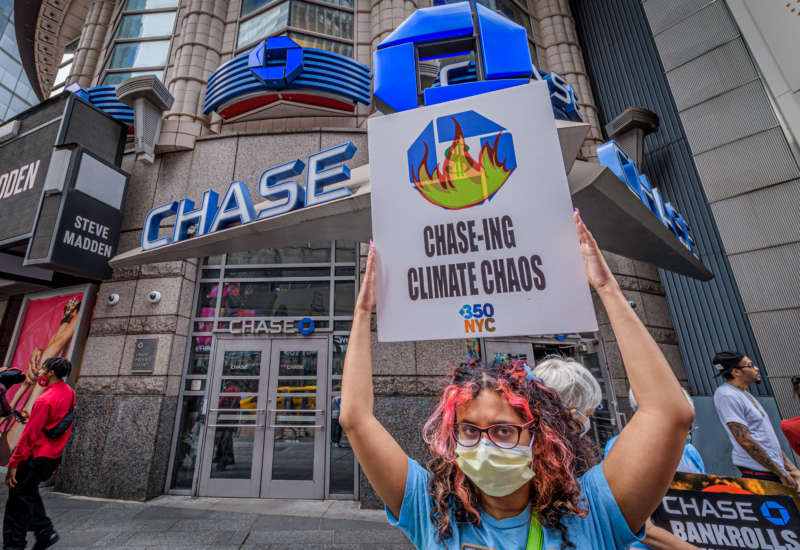

More than 40 climate activists were arrested in New York City while blocking the entrances of JPMorgan Chase, Citibank and Bank of America on the 10-year anniversary of Occupy Wall Street and in the run-up to New York Climate Week and today’s global climate strike. Dozens more risked arrest at Chase, Bank of America and the Canadian consulate in Seattle to demand the institutions stop bankrolling tar sands pipelines.

But even as climate finance activists with the Stop the Money Pipeline coalition celebrate a number of recent divestment wins — including from the MacArthur Foundation, Harvard, Macalester College, major insurer Chubb and the New York State pension fund — not a single major bank has committed to divesting from oil and gas, and all continue to have some exposure to coal, according to the coalition. In fact, the largest fossil fuel financer, JPMorgan Chase, is doubling down on funding oil and gas for years to come despite the International Energy Agency’s report earlier this year calling for an end to new investments in fossil fuels.

That’s why it’s so important, campaigners say, for the Fed to step in and why Stop the Money Pipeline is intensifying an internal White House push to replace Republican Fed Chair Jerome Powell at the end of his four-year term in February 2022.

“We need a new Fed chair who’s more willing to take action on this critical threat to financial stability.”

“Frankly, the Federal Reserve is the most powerful financial regulator and it has done very, very little on climate, basically nothing, and it’s pretty clear Jerome Powell is not looking to do more than the bare minimum on climate, so we need a new Fed chair who’s more willing to take action on this critical threat to financial stability,” says Yevgeny Shrago, who is policy counsel for Public Citizen’s Climate Program.

A Fossil-Free Fed

Last week, another set of progressive House Democratic representatives, Mondaire Jones, Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib, introduced the Fossil Free Finance Act, which would force the Federal Reserve to break up banks if they do not reduce the carbon emissions they finance in line with the Paris Agreement.

Under Powell, the central bank has created several committees focused on climate-related financial risks, but has refused to turn the committees’ recommendations into regulatory requirements. Powell has rejected calls to use the Fed as a tool in the fight to mitigate the climate disaster, insisting it is not appropriate for the Fed to step beyond its mandate.

“We cannot be originalists and textualists when it comes to monetary policy.”

“Congress has the power to increase or shrink the mandate of the Fed. That is fully within their province, so there’s a lot of detractors [of the bill], especially Republicans, saying, ‘That’s not the Fed’s place.’ Well, you know what, the Fed also weighs in on cryptocurrency and matters around racial justice and … issues that didn’t exist when the Fed was first formed,” says Tracey Lewis, a climate finance policy analyst with 350.org. “We cannot be originalists and textualists when it comes to monetary policy…. It gives an air of preserving a history that may not be worthy of preservation.”

She tells Truthout that the Fossil Free Finance Act would protect the stability of the financial system as a whole by protecting against the financial threats banks and insurers increasingly face from unfolding climate disasters, including floods, droughts, wildfires, polar vortexes and heat domes. “Increasing events means increasing loss, which means not just physical loss but financial loss,” she says. “Where we have smaller banks, regional banks, will they be able to absorb that loss? It’s very doubtful.”

Lewis says most campaigners for a Fossil Free Fed want to see Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard replace Powell as Fed chair. Brainard’s strong commitment both to full employment and to strong financial regulation could prove monumental in the success of the Biden administration’s stated agenda of mitigating the financial impacts of the pandemic and climate crisis, as well as addressing deepening structural racism and inequality. Her record stands in strong contrast to Powell’s, whose Fed has weakened Dodd-Frank reforms as well as tools that federal bank regulators use to monitor bank risk-taking and law compliance.

Fossil-free Fed campaigners also want to see progressive economists Sarah Bloom Raskin and Lisa Cook replace Randy Quarles and Richard Clarida as Federal Reserve vice chair of supervision and vice chair, respectively. Cook would be first Black woman to serve on the Fed’s board.

Lewis cited Cook’s work to study the pandemic’s disproportionate impacts on women, especially women of color, from job losses and insufficient caregiving supports that resulted in almost 1.8 million fewer women in the labor force as of May 2021. She says these are the kinds of perspectives the administration should be focused on bringing in to the Fed Reserve board, not the same “white, heteronormative hegemons” whose neoliberal, Milton Friedman-style fiscal policies got us here in the first place.

The Stop the Money Pipeline coalition is also ramping up engagement with the Biden administration as Treasury officials are set to issue a report on the tools available for addressing climate risk in the financial system just after the Glasgow talks.

“It’s a really important report because it could very well serve as a blueprint for regulatory action for federal agencies if it’s bold and meets the Biden administration’s rhetoric on climate.”

“It’s a really important report because it could very well serve as a blueprint for regulatory action for federal agencies if it’s bold and meets the Biden administration’s rhetoric on climate,” Public Citizen’s Shrago says. “It could be a path forward for appointees, including a new Federal Reserve chair, to protect the financial system from the advance of the climate crisis.”

He cautioned that it’s Treasury officials who should be leading the drafting of the report and urged a strong final draft that meets Biden’s climate commitments, rather than a watered-down draft that would come out of a consensus process with the Financial Stability Oversight Counsel, which consists of federal and state financial regulators and insurance experts, including three appointed by Trump. “We don’t think [Treasury] should strive for a consensus document when there’s three people appointed by someone who took no action on climate change and withdrew the United States from the Paris Agreement,” Shrago says.

The push for the bills comes as Chinese President Xi Jinping announced Tuesday that his country will stop building coal-fired power plants overseas. Climate activists cautiously celebrated the announcement by far the biggest domestic producer of coal and the largest financier of coal-fired power plants around the world.

“One of the common criticisms of the climate finance regulation work is that as long as there’s demand for energy or fossil fuels, cutting off money or definancing it really isn’t going to work, because people will just go somewhere else for money, but what you see is even national governments like China are recognizing that these projects aren’t profitable and if you cut off the flow of financing now, it’s going to reduce the amount of fossil fuels in the air later,” Shrago tells Truthout.

“National governments like China are recognizing that these projects aren’t profitable and if you cut off the flow of financing now, it’s going to reduce the amount of fossil fuels in the air later.”

The Chinese commitment comes as banks, asset managers and insurance companies continue to issue much less impactful or meaningless climate commitments that environmentalists are calling out as predictable greenwashing and cynical climate PR ahead of COP26. Bank of America, for instance, while sponsoring New York Climate Week, recently closed a deal to underwrite a new $1.5 billion Canadian, “sustainability-linked” bond for Enbridge, the company behind the Line 3 tar sands pipeline.

Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s $430 billion sovereign wealth fund is expected to announce its first green debt issuance, which raises funds for environmental investments by borrowing money from “green” bonds. It also announced that it will work with notorious fossil fuel funder and shadow bank BlackRock on developing an “environmental social and governance” framework, which Shrago called a climate “net negative” as long as Saudi Aramco, the world’s biggest oil company, continues to extract fossil fuels.

Lastly, Royal Dutch Shell’s recent announcement that it will sell all of its assets in West Texas’s Permian basin to ConocoPhillips for around $9.5 billion is being described a “carbon shell game” by journalists who note that the company is simply offloading fossil fuel production to another company that will continue extraction in the Permian.

“There a bit of a ‘last-one-out’ problem in fossil fuels that it’s important for regulators to think about,” Shrago says. “As more and more people divest from fossil fuels, there’s going to be fewer and fewer buyers, so the next time someone wants to divest, fewer companies will pick up their assets and eventually you’re just going to see a market that dries up, and whenever that happens, whoever is left holding the potato is going to be in a lot of trouble, and there’s going to be a lot of banks, private equity funds, hedge funds and insurance companies that are behind the curve if regulators don’t act.”

The best way to ensure regulators do act, climate finance analysts say, is to retool the most influential financial institution in the country — the Federal Reserve. “This may be the absolute last chance that a Democratic president has to make real changes to the Fed and Fed policy,” 350’s Lewis tells Truthout. “President Biden has an opportunity that was not present for President Obama, not for President Clinton, not for President Carter.”