The overwhelming majority of intellectuals have historically been servants of the status quo.

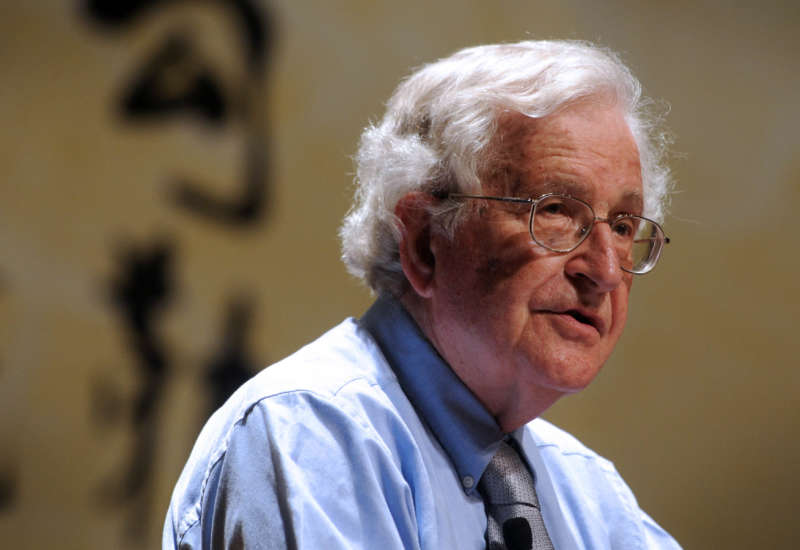

That was the case more than half a century ago, when Noam Chomsky pointed out as much in his classic essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” and it continues to be the case today, when oppositional public intellectuals continue to be a small minority.

Indeed, if anything, the number of critical/oppositional public intellectuals — in other words, thinkers who are versed to speak on a wide range of issues from an anti-establishment standpoint — has been in decline in recent decades, even as the public sphere has grown bigger and louder due to the dramatic expansion of the internet and social media. One factor in this trend may be universities’ overwhelming emphasis on narrow, specialized and even arcane knowledge, and a resistance within academic culture to prioritizing making an impact on the public arena by addressing issues that affect directly people’s lives and challenge the status quo. Another factor may be the rising tide of anti-intellectualism in the U.S. and beyond.

Yet, in a highly fragile world facing existential threats, we need the voice of critical intellectuals more than any other time in history. In the interview that follows, Noam Chomsky — the scholar, public thinker and activist who has been described as a “world treasure’” and “arguably the most important intellectual alive” — discusses the urgent need for more intellectuals not to “speak truth to power” but to speak with the powerless.

C.J. Polychroniou: Long ago, in your celebrated essay “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” you argued that intellectuals must insist on truth and expose lies, but must also analyze events in their historical perspective. Now, while you never implied that this is the only responsibility that intellectuals have, don’t you think that the role of intellectuals has changed dramatically over the course of the last half century or so? I mean, true, critical/oppositional intellectuals were always few and far between in the modern Western era, but there were always giants in our midst whose voice and status were not only revered by a fair chunk of the citizenry, but, in some cases, produced fear and even awe among the members of the ruling class. Today, we have mainly functional/conformist “intellectuals” who focus on narrow, highly specialized and technical areas, and do not dare to challenge the status quo or speak out against social evils out of fear of losing their job, being denied tenure and promotion, or not having access to grants. Indeed, whatever happened to public intellectuals like Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre, and to iconic artists like Picasso with his fight against fascism?

Noam Chomsky: Well, what did happen to Bertrand Russell?

Russell was jailed during World War I along with the handful of others who dared to oppose that glorious enterprise: Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, Eugene Debs — who was even excluded from postwar amnesty by the vengeful Woodrow Wilson — to mention only the most famous. Some were treated more kindly, like Randolph Bourne, merely ostracized and barred from liberal intellectual circles and journals. Russell’s later career had many ugly episodes, including his being declared by the courts to be too free-thinking to be allowed to teach at City College, a flood of vilification from high places because of his opposition to the Vietnam War, scurrilous treatment even after his death.

Not all that unusual for those who break ranks, no matter how distinguished their contributions, as Russell’s surely were.

The task of anyone who wants to uphold intellectual and moral values is not to speak what they regard as truth to anybody — the powerful or the powerless — but rather to speak with the powerless and to try to learn the truth.

The term “intellectual” itself is a strange one. It is not applied to a Nobel laureate who devotes his life to physics, or to the janitor in his building who may have little formal education but deep insight and perceptive understanding of human affairs, history, culture. The term is used, usually, to refer to a category of people with a degree of privilege who are somehow regarded to be the guardians of society’s intellectual and moral values. They are supposed to uphold and articulate those values and call upon others to adhere to them.

Within this category there is a small minority who challenge power, authority and received doctrine. It is sometimes held that their responsibility is “to speak truth to power.” I’ve always found that troubling. The powerful typically know the truth quite well. They generally know what they are doing, and don’t need our instructions. They also will not benefit from moral lessons, not because they are necessarily bad people, but because they play a certain institutional role, and if they abandon that role, somebody else will fill it as long as the institutions persist. There is no point instructing CEOs of the fossil fuel industry that their activities are damaging communities and destroying the environment and our climate. They’ve known that for a long time. They also know that if they depart from dedication to profit and concern themselves with the human impact of what they are doing, they’ll be out on the streets and someone will replace them to carry out the institutionally required tasks.

There remains a range of options, but it is narrow.

It would make a lot more sense to speak truth not to power, but to its victims. If you speak truth to the powerless, it’s possible that it could benefit somebody. It might help people confront the problems in their lives more realistically. It might even help them to act and organize in such ways as to compel the powerful to modify institutions and practices; and, even more significantly, to challenge illegitimate structures of authority and the institutions on which they are realized and thereby expand the scope of freedom and justice. It won’t happen in any other way, and it’s often happened in that way in the past.

But I don’t think that’s right either. The task of a responsible person — anyone who wants to uphold intellectual and moral values — is not to speak what they regard as truth to anybody — the powerful or the powerless — but rather to speak with the powerless and to try to learn the truth. That’s always a collective endeavor and wisdom and understanding need not come from any particular turf.

But that’s quite rare in the history of intellectuals.

Let’s recall that the term “intellectual” came into use in its modern sense with the Dreyfus trial in France in the late 19th century. Today we admire and respect those who stood up for justice in their defense of Dreyfus, but if you look back at that time, they were a persecuted minority. The “immortals” of the French Academy bitterly condemned these preposterous writers and artists for daring to challenge the august leaders and institutions of the French State. The prominent figure of the Dreyfusards, Emile Zola, had to flee from France.

That’s pretty typical. Take almost any society you like and you will find that there is a fringe of critical dissidents and that they are usually subjected to one or another form of punishment. Those I mentioned are no exception. In recent history, in Russian-run Eastern Europe, they could be jailed; if it was in our own domains, in Central or South America, they could be tortured and murdered. In both cases, there was harsh repression of people who are critical of established power.

That goes back as far as you like, all the way back to classical Greece. Who was the person who drank the hemlock? It was the person who was “corrupting” the youth of Athens by asking searching questions that are better hidden away. Take a look at the Biblical record, roughly about the same period. It’s kind of oral history, but in what’s reconstructed from it, there were people who by our standards might be called intellectuals — people who condemned the king and his crimes, called for mercy for widows and orphans, other subversive acts. How were they treated? They were imprisoned, driven into the desert, reviled. There were intellectuals who were respected, flatterers at the Court. Centuries later, they were called False Prophets, but not at the time. And if you think through history, that pattern is replicated quite consistently.

The basic operative principle was captured incisively by McGeorge Bundy, a leading liberal intellectual, noted scholar, former Harvard dean, national security adviser under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, then director of the Ford Foundation. In 1968, when protest against the Vietnam War was peaking, Bundy published an article in the main establishment journal Foreign Affairs in which he discussed protest against the war. Much of the protest was legitimate, he conceded: there had in retrospect been some mistakes in managing such a complex effort. But then there was a fringe of “wild men in the wings” who merit only contempt. The wild men actually descended so far as to look into motives. That is, they treated the U.S. political leadership by the standards applied to others, and hence must be excluded from polite company.

The “technocratic and policy-oriented intellectuals” [are considered] the good guys who orchestrate and inform policy, and are duly honored for their constructive work — the Henry Kissingers, who loyally transmit orders for a massive bombing campaign.

Bundy’s analysis was in fact the norm among liberal intellectuals. Their publications soberly distinguished the “technocratic and policy-oriented intellectuals” from the “value-oriented intellectuals.” The former are the good guys, who orchestrate and inform policy, and are duly honored for their constructive work — the Henry Kissingers, the kind who loyally transmit orders from their half-drunk boss for a massive bombing campaign in Cambodia, “anything that flies against anything that moves.” A call for genocide that’s not easy to duplicate in the archival record. The latter are the wild men in the wings who prate about moral value, justice, international law and other sentimentalities.

The U.S. isn’t El Salvador. The wild men don’t have their brains blown out by elite battalions armed and trained in Washington, like the six leading Latin American intellectuals, Jesuit priests, who suffered this fate along with their housekeeper and her daughter on the eve of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Who even knows their names? Properly, one might argue, since there were many other religious martyrs among the hundreds of thousands slaughtered in Washington’s crusade in Central America in the 1980s, managed with the assistance of technocratic and policy-oriented intellectuals.

It is, regrettably, all too easy to continue.

I believe it would be of great interest if you talked about the historical context of “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” but also if you elaborate on what you mean when you say intellectuals must see events from their historical perspective.

The essay was based on a talk given in1966 to a student group at Harvard. It was published in the group’s journal. They’ve probably expunged it since. It was the Harvard Hillel Society. The journal is Mosaic. This was a year before Israel’s military victory in 1967, a great gift to the U.S., which led to a sharp re-orientation in U.S.-Israeli policies and major shifts in popular culture and attitudes in the U.S. — an interesting and important story, but not for here.

The New York Review of Books published an edited version.

Since the talk was at Harvard, it was particularly important to focus on intellectual elites and their special links to government. The Harvard faculty was quite prominent in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. Camelot mythology is in considerable part their creation. But as we’ve been discussing, it’s just one phase in a long history of intellectual service to power. It’s still unfolding without fundamental change, though the activism of the ‘60s and its aftermath has substantially changed much of the country, widening the wings in which “wild men” can pursue their value-oriented subversion.

This impact has also greatly broadened the historical perspective from which events of the world are perceived. No one today would write a major diplomatic history of the U.S. recounting how after the British yoke was overthrown, the former colonists, in the words of Thomas Bailey, “concentrated on the task of felling trees and Indians and of rounding out their natural boundaries” — in “self-defense,” of course. Few in the ‘60s fully grasped the fact that our “forever wars” began in 1783. The horrendous 400-year record of torture of African Americans was also scarcely acknowledged by mainstream academics; more, and worse, is constantly being unearthed. The same is true in other areas. Dedicated and conscientious activism can open many windows for valuable historical perspective to be gained.

The world has changed a great deal since the era of the Vietnam War, and I think you would agree with me that we are facing greater challenges today than ever before. Moreover, we live in a much smaller world, and some of the challenges facing us are truly global in nature and scope. In that context, what should be the role of intellectuals and of social movements in a globalized world and with a shared future for humanity?

You’re quite right that we face far greater challenges today than during the Vietnam era. In 1968, when liberal intellectuals were excoriating the value-oriented “wild men,” the leading issue was that “Viet-Nam as a cultural and historic entity [was] threatened with extinction [as] the countryside literally dies under the blows of the largest military machine ever unleashed on an area of this size,” the judgment of the most respected Vietnam specialist, military historian Bernard Fall.

We are living in an era of confluence of crises that has no counterpart in human history.

It is now organized human society worldwide that is “threatened with extinction” under the blows of environmental destruction, overwhelmingly by the rich, concentrated in the rich countries. That’s apart from the no less ominous and growing threat of nuclear holocaust, being stoked as we speak.

We are living in an era of confluence of crises that has no counterpart in human history. For each of these, feasible solutions are known, though time is short. There is no need to waste words on responsibility.

Who is undertaking the historic task of addressing these crises? Who carried out the Global Climate Strike on September 24, a desperate attempt to wake up the dithering leaders of global society, and citizens who have been lulled into passivity by elite treachery? We know the answer: the young, the inheritors of our folly. It should be deeply painful to witness the scene at Davos, the annual gathering where the rich and powerful posture in their self-righteousness, and applaud politely when Greta Thunberg instructs them quietly and expertly on the catastrophe they have been blithely creating.

It’s clear the rich are thinking: Nice little girl. Now go back to school where you belong and leave the serious problems to us, the enlightened political leaders, the soulful corporations working day and night for the common good, the responsible intellectuals. We’ll take care of it, ensuring that the betrayal will be apocalyptic — as it will be, if we grant them the power to run the world in accord with the principles they have established and implemented.

The principles are not obscure. Right now, governments of the world, the U.S. foremost among them, are pressuring oil producers to increase production — having just been advised in the August IPCC report, by far the direst yet, that catastrophe is looming unless we begin right now to reduce fossil fuel use year by year, effectively phasing them out by mid-century. Petroleum industry journals are euphoric about the discovery of new fields to exploit as demand for oil increases. The business press debates whether the U.S. fracking industry or OPEC is best placed to increase production.

Congress is debating a bill that might have slightly slowed the race to destruction. The denialist party is 100 percent opposed, so the fate of legislation is in the hands of the “moderate” Democrats, particularly Joe Manchin. He has made his position on climate explicit: “Spending on innovation, not elimination.” Straight out of the playbook of PR departments of the fossil fuel companies, no surprise from Congress’s leading recipient of fossil fuel compensation. Fossil fuel use must continue unimpeded, driving us to catastrophe in the interests of short-term profit for the very rich. Period.

On the rest of the Biden package, Manchin — the swing vote — has made it clear that he will accept only a trickle, also insisting on cumbersome and degrading means testing for what is standard practice in the civilized world. The posture is certainly not for the benefit of his constituents. As for other “moderates,” it is much the same. Without far more intense public pressure, there was never much hope that this Congress would allow the country to begin to beat back the cruel assault of overwhelming business power.

There is no need to tarry on what this entails about responsibility.

And again, we dare not neglect the cloud that was cast over the world by human intelligence 75 years ago and has been darkening in recent years. The arms control regime that had been laboriously constructed over many decades has been systematically dismantled by the last two Republican administrations, first Bush II and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, then Trump wielding his wrecking ball with abandon. He left office barely in time for Biden to salvage the New START Treaty, accepting Russia’s pleas to extend it. Biden continues, however, to support the bloated military budget, to pursue the race to develop more dangerous weapons, and to carry out highly provocative acts where diplomacy and negotiations are surely possible.

A major point of contention right now is “freedom of navigation” in the South China Sea. More accurately, as Australian strategic analyst Clinton Fernandes points out, the conflict concerns military/intelligence operations in China’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 miles offshore. The U.S. holds that such operations are permissible in all EEZs. China holds that they are not. India agrees with China’s interpretation, and vigorously protested recent U.S. military operations in its EEZ.

EEZs were established by the 1982 Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The U.S. is the only maritime power not to have ratified the Law, but asserts that it will not violate it. The relevant wording about military operations in the Law is not entirely precise. Surely this is a clear case where diplomacy is in order, not highly provocative actions in a region of considerable tension, with the threat of escalation, possibly without bounds.

All of this is part of the U.S. effort to “contain China.” Or, to put it differently, to establish “The fact that somehow, the rise of 20 per cent of humanity from abject poverty into something approaching a modern state, is illegitimate — but more than that, by its mere presence, an affront to the United States. It is not that China presents a threat to the United States — something China has never articulated nor delivered — rather, its mere presence represents a challenge to United States pre-eminence.”

This is the quite realistic assessment of former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating, reacting to the recent AUKUS (Australia-U.K.-U.S.) agreement to sell eight advanced nuclear submarines to Australia, to be incorporated in the U.S. naval command in order to respond to the “threat of China.”

The agreement abrogates a France-Australia agreement for sale of conventional subs. With typical imperial arrogance, Washington did not even notify France, instructing the European Union on its place in the U.S.-run global order. In reaction, France recalled its ambassadors to the U.S. and Australia, ignoring the U.K., a mere vassal state.

Australian military correspondent Brian Toohey observes that Australia’s submission to the U.S. does not enhance its security — quite the contrary — and that AUKUS has no discernable strategic purpose. The subs will not be operational for over a decade, by which time China will surely have expanded its military forces to deal with this new military threat, just as it has done to deal with the fact that it is ringed by nuclear-armed missiles in some of the 800 military bases that the U.S. has around the world (China has one, Djibouti).

Toohey outlines the naval military balance that is disrupted further by AUKUS. It’s worth quoting directly to help understand how China threatens the U.S. — not in the Caribbean or the California coast, but on China’s borders:

China’s nuclear weapons are so inferior that it couldn’t be confident of deterring a retaliatory strike from the US. Take the example of nuclear-powered, ballistic missile-armed submarines (SSBNs). China has four Jin-class SSBNs. Each can carry 12 missiles, each with a single warhead. The subs are easy to detect because they’re noisy. According to the US Office of Naval Intelligence, each is noisier than a Soviet submarine first launched in 1976. Russian and US subs are now much quieter. China is expected to acquire another four SSBNs that are a little quieter by 2030. However, the missiles on the subs won’t have the range to reach the continental US from near their base on Hainan island in the South China Sea. To target the continental US, they would have to reach suitable locations in the Pacific Ocean. However, they are effectively bottled up inside the South China Sea. To escape, they have to pass through a series of chokepoints where they would be easily sunk by US hunter killer nuclear submarines of the type the [Australian] Morrison government wants to buy. In contrast, the US has 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. Each can launch 24 Trident missiles, each containing eight independently targetable warheads able to reach anywhere on the globe. This means a single US submarine can destroy 192 cities, or other targets, compared to 12 for the Chinese submarine. The Ohio class is now being replaced by the bigger Columbia class. These [are being] constructed at the same time as new US hunter killer submarines.

That’s before eight new advanced nuclear subs are built for Australia. In nuclear forces generally and other relevant military capacity, China is of course far behind the U.S., as are all potential U.S. adversaries combined.

AUKUS does serve a purpose, however: to establish more firmly that the U.S. intends to rule the world, even if that requires escalating the threat of war, possibly terminal nuclear war, in a highly volatile region. And eschewing such “sissified” measures as diplomacy.

It is not the only example. One of these should have been on the front pages in the past few weeks as the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan, executing Trump’s cynical sell-out of Afghans in his February 2020 deal with the Taliban.

The obvious question is: Why did the Bush administration invade 20 years ago? The U.S. had no interest in Afghanistan, as Bush’s pronouncements at the time made explicit; the real prize was Iraq, then beyond. Bush also made it clear that the administration also had little interest in Osama bin Laden or al-Qaeda. That lack of concern was made fully explicit by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld when the Taliban offered surrender. “We do not negotiate surrenders,” Rumsfeld stormed.

The only plausible explanation for the invasion was given by the most highly respected leader of the anti-Taliban resistance, Abdul Haq. He was interviewed shortly after the invasion by Asia scholar Anatol Lieven.

Haq said that the invasion will kill many Afghans and undermine promising Afghan efforts to undermine the Taliban regime from within, but that’s not Washington’s concern: “the US is trying to show its muscle, score a victory and scare everyone in the world. They don’t care about the suffering of the Afghans or how many people we will lose.”

That also seems a fair description of current U.S. strategy in “containing the China threat” by provocative escalation in place of diplomacy. It’s no innovation in imperial history.

Returning to the responsibility of intellectuals and how it is being fulfilled, no elaboration should be necessary.