When President Joe Biden toured storm-ravaged neighborhoods in Louisiana in September, he portrayed the damage of Hurricane Ida as a national issue. He claimed that “its destruction is everywhere,” and even more so, that, “it’s a matter of life and death, and we’re all in this together.” As comforting as it may be to hear the president taking storm relief seriously, Biden is getting it wrong.

Natural disasters could not care less about the unity of the American people. And they hurt underprivileged communities the most.

The year 2005 showed us a preview of how storms can unleash massive social and economic disruption. Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast that August, causing the loss of almost 2,000 lives and an estimated $125 billion in damage. Cities like New Orleans were swarmed with images of poor, mostly Black residents navigating the flooded streets.

Floodwater had broken through the frail levees of New Orleans and taken over the Lower Ninth Ward, an overwhelmingly poor and Black area. Emergency food and medical aid took five days to come. A group of military contractors and the National Guard later organized the full evacuation of the city. Since then, Katrina has become a widely recognized symbol of neglect towards poor and Black communities, in addition to a blatant case of environmental injustice.

Several studies in the aftermath of Katrina have exposed the relationship between the hurricane and class or racial divides. Research confirms that the storm damage was concentrated in low-income areas. In fact, there is substantive evidence that low-income people — particularly in communities of color — had been disproportionately vulnerable to unemployment and decreasing housing availability in the years following the storm.

These unequal levels of devastation are not unique to Katrina. A 2018 paper pointed out that wealth inequality increases with the frequency and intensity of natural hazards, especially along lines of race, education and homeownership.

For example, during a period of substantial natural hazards between 1999 and 2013, white Americans living in counties with $10 billion worth of property damage from storms gained an average net worth of $126,000 per county. Black Americans in the same areas lost $27,000 per county. Similar trends are visible when comparing college-educated to non-college-educated Americans, as well as comparing home-owning to non-home-owning Americans.

It turns out that natural hazards are really good at making poor people poorer, and rich people richer.

The more FEMA aid a county receives, the starker the wealth disparities become within its residents.

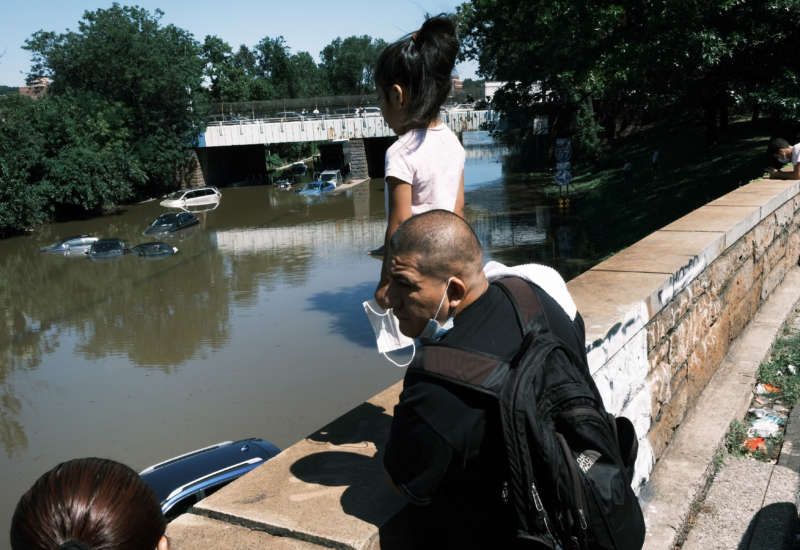

While hurricanes chase some people out of their homes and trap them into poverty, risk-taking investors follow the storm path in order to buy property that will make them even wealthier. Less obvious ways to make money from storms include selling flood-damaged cars without disclosing the damage (yes, this is legal), payday lending to desperate financially insecure people, or selling protective materials and simultaneously funding climate denial lobbies. These tactics purposely take advantage of vulnerable populations for profit. They are, by definition, predatory.

What’s even more concerning is that federal aid doesn’t help reduce inequalities in the wake of a storm. For the past couple of decades, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has offered billions of dollars to counties and individuals coping with storm damage. Yet the more FEMA aid a county receives, the starker the wealth disparities become within its residents, possibly due to misallocation of funds. At the same time, private sources of community reinvestment are concentrated in predominantly white middle-class communities.

This means that — like many others in the past — the current hurricane season created more than a natural disaster. It also fueled a social, economic and cultural calamity.

FEMA has already filed over half a million applications since Ida. To date, it is the second-most intense hurricane to have hit the state of Louisiana, right behind Katrina. Moreover, Ida triggered a tornado outbreak and flash flooding across the Northeast, making it one of the costliest tropical cyclones in U.S. history.

Could the situation get any worse?

Actually, it probably will.

Hurricanes form in the Atlantic Ocean every year, June through November. National climate prediction centers are expecting 2021 to be an exceptionally active season for tropical cyclones. In the upcoming years, hurricanes will likely only get stronger and more frequent as global temperatures continue to rise.

This is an opportunity to do better: Apply the lessons learned from Katrina, commit to the fight against environmental injustice and pay more attention to the wealth trajectories of the country.

If previous natural disasters taught us anything, it’s that we cannot abandon those who need the most assistance after a storm. Katrina exemplified how relying exclusively on the private sector and the military for disaster relief can lead to exploitation and violence. Instead, we must prevent large-scale physical damage by strengthening the infrastructure of hazard-prone areas. Furthermore, legislators should put a halt to predatory private companies and individual profiting from natural hazards — from enforcing laws against price gauging to banning the sale of damaged goods without disclosure. In the event of a natural hazard, FEMA should provide emergency aid quickly and equitably.

It’s imperative that policymakers launch focused and comprehensive reforms that provide aid beyond short-term economic recovery. These could include targeted reemployment programs, unemployment benefits, relocation assistance, rent subsidies, education grants or infrastructural support — possibilities for holistic recovery following a natural disaster are endless.

Making people feel united after a harrowing hurricane is cute. Now it’s time for the Biden administration to really address the aftermath of Ida.