Last week, just days after the Arizona legislature passed the most expansive school voucher law anywhere in the nation, Gov. Doug Ducey signed into law another education measure decreeing that public school teachers are no longer required to have a college degree of any kind before being hired. Instead of requiring a masters degree — which has long been the norm in the profession — Arizona teachers will only have to be enrolled in college in order to begin teaching the state’s public school students.

The law, SB 1159, was pushed by conservatives on the grounds that Arizona has faced a severe teacher shortage for the last six years, which, by this winter, left 26% of teacher vacancies unfilled and nearly 2,000 classrooms without an official teacher of record. That shortage has led supporters of the bill, including business interests such as the Arizona Chamber of Commerce, to claim that loosening teacher credential requirements will help fill those staffing gaps. Opponents of the bill, however, point to the fact that Arizona has the lowest teacher salaries in the country, even while boasting a budget surplus of more than $5 billion.

“Arizona’s teacher shortage is beyond crisis levels,” tweeted Democratic state Rep. Kelli Butler this March. “Instead of offering real solutions (like increasing pay & reducing class sizes) the House Education Committee passed a bill to reduce the requirements to teach.”

“With Arizona trying to get education monies to parents directly to pay for schooling — including homeschooling — you see more evidence that the state doesn’t care who teaches its kids,” said David Berliner, an education psychologist at Arizona State University and former president of the American Educational Research Association. “Charters and private schools for years have not needed certified folks running schools or teaching kids — as long as the voucher for the kids shows up.” Combined with its new law creating a universal voucher system, Berliner added, “Arizona may now be the most radical state in terms of education policy.”

But Arizona also isn’t alone. In fact, attacks on teacher credentials or teacher education have been piling up in recent months.

Teaching candidates with advanced degrees, says anti-CRT activist Christopher Rufo, should be viewed with suspicion: Don’t “hire the ones with the masters, because those are the crazies.”

In April, anti-CRT activist Christopher Rufo called for state lawmakers to rescind requirements that teachers hold education degrees, claiming that masters programs in education only exposed future teachers to left-wing ideology. Instead, Rufo argued, public schools should only require bachelor’s degrees for new hires, predicting that in time school officials would come to view applicants with advanced degrees as suspicious: Don’t “hire the ones with the masters, because those are the crazies.”

Earlier this month, Tennessee’s NewsChannel 5 reported that Larry Arnn, president of Hillsdale College, an influential conservative institution that oversees a nationwide network of charter schools, had denigrated public school teachers in harsh terms during a private event with Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee, describing them as products of “the dumbest parts of the dumbest colleges in the country.”

Just last week, as Salon reported, a new set of “model” social studies state standards released by a right-wing coalition called the Civics Alliance took a detour into teacher credentialing. While most of the model standards covered guidance for state legislators to press for anti-“woke” history and civics curricula (i.e., lectures on the “George Floyd Riots” or how America’s founding principles are “rooted in Christian thought”), the document also calls for reforming teaching licensing processes so as to “end the gatekeeping power of the education schools and departments.”

None of this is coincidental. In February, the right-wing bill mill American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, described “alternative credentialing” of teachers as one of its “essential policy ideas” for 2022 — part of a three-pronged education agenda that also includes plans to expand “parental rights” and “school choice.”

In fact, ALEC, which has included staffers of online for-profit school corporations among its leadership, has had a model bill called the Alternative Certification Act available for state legislators to adopt since 2005. As Brendan Fischer and Zachary Peters wrote at PR Watch, versions of the act were introduced in four states by 2016, including Wisconsin, which also surreptitiously added a provision to its budget in 2015 allowing people without even high school degrees to teach some public school subjects (which apparently went too far for Wisconsin voters).

“Along with its bills supporting minimum wage repeal, living wage repeal, prevailing wage repeal,” Peters and Fischer wrote, “the ‘alternative certification’ bill and ALEC’s union-busting portfolio can be viewed as part of ALEC’s ongoing effort to undermine an educated and well-paid workforce and promote a race to the bottom in wages and benefits for American workers.”

But this standing agenda item has recently become a far more substantial part of conservatives’ attack on public education. In 2020, Frederick Hess, director of education policy at the American Enterprise Institute, argued that the “teacher-licensure racket” should become part of the right’s education agenda, helping pave the way toward a radical reimagining of teachers’ jobs.

Now many conservatives want to undo the “teacher-licensure racket,” undermining unions and university education programs and paving the way toward a radical reimagining of teachers’ jobs.

“Dislodging a complicated, bureaucratic sector will entail pilot projects, philanthropy, and energetic leadership at the state and local levels,” Hess wrote in an article at National Affairs. But such an all-hands effort could spark a chain of events, he continued: First, governors would push their education commissioners to establish new teacher job descriptions. Those new job descriptions would in turn require new sorts of training programs, “ideally out from under the roofs of traditional education schools.” That would in turn force changes on both education unions — a longstanding bête noire of the right — and university education programs, which Hess envisioned being subjected to “the same healthy market pressures” that other unlicensed professions, such as business or journalism, face. “Absent a licensure requirement, the question will be whether programs are equipping graduates with essential skills and knowledge,” Hess wrote. “If so, programs will prosper; if not, they will not.”

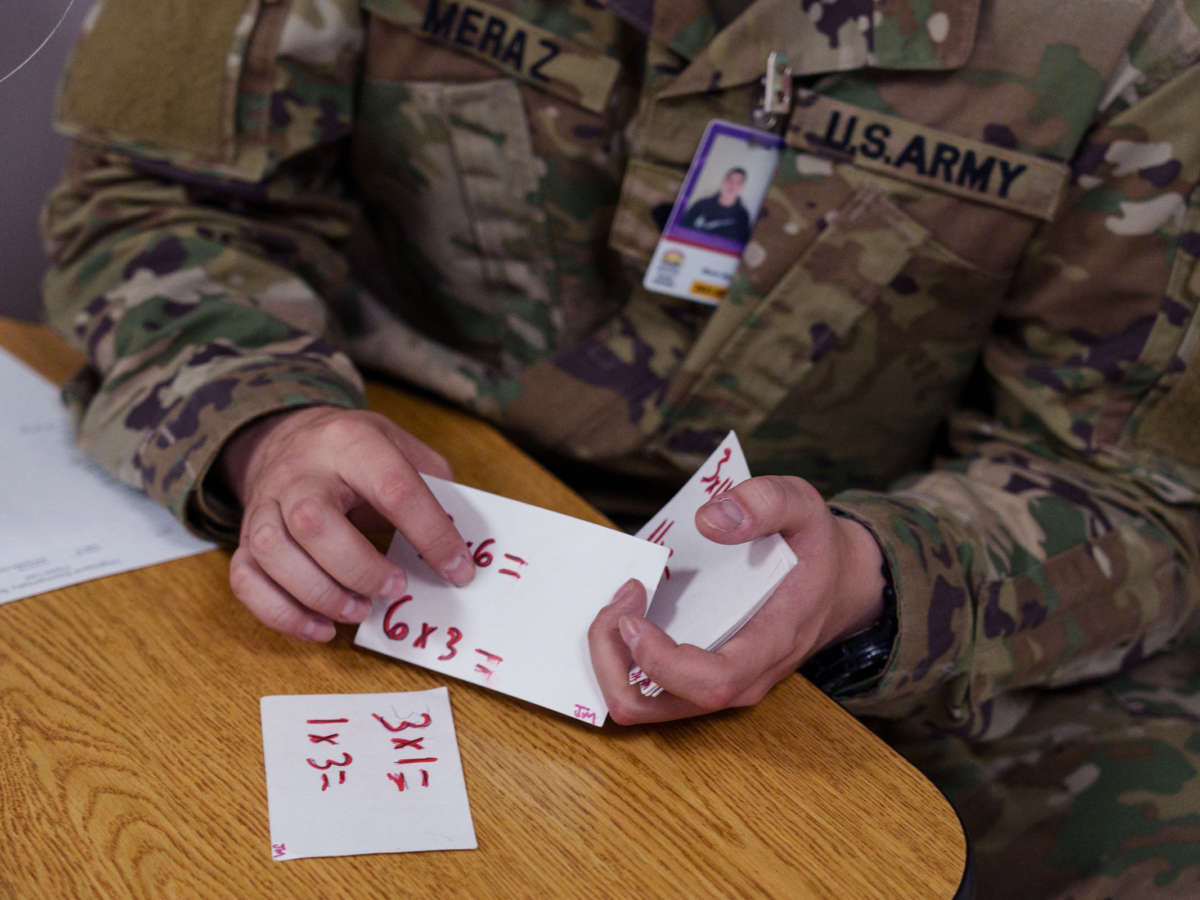

In 2021, other conservative leaders took up the cause. In an American Conservative article entitled “Sick of the Teachers,” conservative legal commentator George Liebmann declared that elementary school teachers shouldn’t be required to have more than one term of instruction in pedagogy, and secondary teachers shouldn’t be required to have any at all. Such changes, he argued, would eliminate “the protective tariff that excludes 90 percent of college graduates from the teaching force,” and would both open the schoolhouse door to “educated housewives,” veterans and retired police and also “break the educationist monopoly in our public schools.”

Last July, conservative writer and political scientist Samuel Goldman proposed that conservatives undertake “a long march through existing institutions,” including by changing teacher certification procedures. In order to stop “losing the education wars,” he wrote, conservatives should “devote themselves to influencing public schools in every capacity and at every education level,” creating “something like a Federalist Society for educators” as well as reforming teacher certification rules such as to “limit the influence of progressive gatekeepers.” Even if that didn’t change anything in the classroom, Goldman argued, it might at least “offer some protection against dubious anti-bias training” and what he called “compelled speech in administrative settings.”

Several months later, in September, the American Enterprise Institute published a report, “Rethinking Teacher Certification to Employ K-12 Adjunct Teachers,” which, as the title suggests, called for public schools to “follow the example of colleges and universities in leveraging the advantages of adjunct teachers.” That is, public schools should start hiring part-time, temporary staff to teach at least some classes, with no job security or benefits, and, for students, no guarantee that their teachers will be a stable presence. Despite how poorly that model has panned out in higher education, AEI argued that conservatives “should champion modifying teacher certification laws to allow for adjunct teachers because it gives localities more control over schools, employs free-market principles, increases competition to improve teaching and student outcomes, and provides an avenue for breaking liberal teacher union power over public education.”

Another proposed reform: “Leveraging the advantages of adjunct teachers,” meaning part-time temporary teaching staff with no job security or benefits.

Conservative states, it seems, have been paying attention. This February Politico reported that, as states have scrambled to find teachers to fill staffing gaps during the pandemic, more than two dozen legislatures have introduced bills aimed at recruiting more teachers, often by proposing loosening credential requirements. In Kansas, that has meant allowing 18-year-old high school graduates to work as substitute teachers. In Arizona, even before SB 1159, it meant dispensing with limits on how long substitute teachers could fill roles meant to be held by licensed teachers.

In Idaho, as education writer Peter Greene noted at Forbes last week, a failed 2021 bill that would have allowed all local school districts to craft their own teacher qualifications — except for bare-bones state mandates that teachers must be over 18, have a college degree, pass a background check and not have communicable diseases — was successfully reintroduced for charter schools. “Supporters for the new law argue that it’s a necessary remedy to the teacher shortage,” Greene wrote. “But solving a ‘shortage’ by redefining the thing you are having trouble finding doesn’t actually solve anything.”

Teacher organizations, reported Politico, call such moves “union busting.” Public education advocates call it a race to the bottom — a race that currently has Arizona taking the lead.

“It is both frightening and terrifying that there is a concerted effort on the right to make schools places where fewer young adults want to be, and then respond to the teacher shortage not by improving working conditions or pay, but by watering down credentials,” said Carol Corbett Burris, executive director of the Network for Public Education. “It reflects a hostile and dismissive perception of the profession of teaching — one that was well-reflected in the recent comments of Hillsdale College President Arnn, who claimed, regarding teaching, ‘basically anybody can do it.’”

“It is even more troubling,” Burris continued, “that when the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools heard that Idaho had watered down credentials for charter school teachers, they claimed that as a victory. Apparently many do not treasure our children enough to believe that they deserve a well-prepared and professional teacher to nurture, guide and supervise them all day.”