The movement to create public banks is gaining ground in many parts of the U.S., particularly as part of an effort among activists and progressive lawmakers to extend banking access to low-income communities and communities of color in the post-COVID-19 economy. But how does public banking help protect the local community and assist with development? If public banks become part of the Federal Reserve — as a bill introduced by Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez aims to do — what would be the consequences? Leading progressive economist Gerald Epstein, professor of economics and co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, has studied the issue of public banking extensively and sheds ample light on these questions in this exclusive interview for Truthout.

C.J. Polychroniou: After a series of ups and downs, the movement for public banking is gaining traction in states in the U.S. Why do we need public banks, and why are they a better alternative than private banks?

Gerald Epstein: First off, when I discuss a public bank or a public banking and finance institution, I generally mean a financial institution that has public support, has a social or public goal, and is not driven mainly by a profit motive.

Why do we need public banking institutions? Plenty of reasons. Private banks charge excessive fees for simple banking services. Asset management companies and financial advisers have major conflicts of interest. Banks engage in highly risky activities, expecting bailouts when they get into financial trouble. Private equity firms strip businesses and households of their assets by loading them up with debts, leaving them without the wherewithal to pay decent wages or compete with other companies.

The public provision of financial services is important not only because it can do what the current financial system does not do, but it can do better at many of the things that private finance purports to do. A public banking and financial institution could help restructure the financial system to better serve public needs, especially the short-term and long-term needs of the poor, the working class and the planet.

Here are some important functions that a public banking and financial institution could play in our economy:

Competition and regulation: Public options compete with existing financial institutions, thereby providing people with alternatives to private finance and possibly improving the products and services that private finance offers. The public option also provides a means of regulating private financial institutions through competition.

Public goods: Public goods, such as a highly educated population, efficient infrastructure, and long-term technological innovation with broad positive spillovers, can be supported by public finance institutions.

Collective goods and complementarities: Collective goods are those that require concerted and collective action to come to fruition and generate productive outcomes. For example, as Mehrsa Baradaran argues in developing her proposal for “A Homestead Act for the 21st Century,” providing affordable housing is not sustainable in and of itself because there are a number of complementary goods that must be available at the same time, such as jobs, financial institutions and grocery stores. Here, community development is a good that must involve collective planning and simultaneous financing in a number of different areas for any of the pieces to succeed. A public banking and financial institution can be a useful mechanism to coordinate and help finance these activities.

Financial inclusion — fighting poverty, exploitation and racial discrimination: Financial exclusion, exploitation and racial injustice are deeply ingrained social ills in the United States. Public banking and finance institutions can help finance affordable housing, cooperatives, small businesses, education initiatives and financial services, all in communities of color and for institutions owned or controlled by members of the community.

Financial resilience and stability: Public banking and finance institutions, by contributing to a diverse financial ecosystem, help to make the financial system more resilient and robust. For example, unlike for-profit banks, publicly oriented financial institutions tend to perform countercyclically, helping to stabilize the economy rather than exacerbating crises.

Economic transformation: For large-scale transformative issues, the social provision of finance must play a major role. These include projects that have long-term gestation periods, massive uncertainty, large economies of scale, and the need for complementary investments and planning. One example is the pressing need to make the transition to renewable and non-carbon-producing fuels, such as the Green New Deal. This requires investment in new technologies and infrastructure implementation. In such a multifaceted transformative endeavor, public provision of finance is crucial as a facilitating mechanism and a planning tool.

Promote full employment and good jobs: Credit allocation is key for job creation, including areas of structural unemployment, as well as patient capital for long-term gestation projects and infrastructure investments. Here, the quality of employment is as critical as the quantity (“high road” employment).

Instrument of public policy: In an economic transformation like the Green New Deal, public provision of credit is a powerful instrument of government policy. Countries that have made successful, rapid and transformative economic changes, including the United States, South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Western European countries, such as France, Germany and Italy in the first few decades after World War II, all used public provision of finance as a carrot or stick to elicit desired corporate behavior and allocate credit to priority sectors.

Reducing the power of financial elites and countering capital strike: Among the most important effects of a public banking and financial institution — and a key reason that capitalists often oppose it — is that having a public option reduces the market power of private capital and the political power of finance. As private banks and other financial activities in the United States have become bigger and more concentrated, social provision of finance will confront these oligopolies with more competition. Politically, public options reduce the power of the threat of a capital strike and of being “too big to fail.” With a large public banking and financial institution footprint, we can say to Wall Street, “Go ahead and fail. Our public financial institutions will provide the needed services without you.” Moreover, public banking and financial institutions provide a counterweight if private finance threatens capital flight in response to progressive policies they don’t like.

Can public banking and finance institutions thrive and survive in a capitalist economy?

The origins of the resurgence of interest in public banking go back to the Occupy Movement.

Capitalist economies, especially those dominated by neoliberalism, would seem to be a uniquely inhospitable place for public banking and finance. Yet, as Thomas Marois has documented, there has been a dramatic increase in public banking and financial institutions’ prevalence around the world in recent decades. According to him, over 900 public banks currently exist. Altogether, they control more than 20 percent of all bank assets, public and private. While it is true that public control of banking assets has probably fallen from its 1970s height of around 40 percent, today’s economies are much bigger, and the total mass of public bank capital has grown substantially. The latest estimate by Marois shows that public banks have combined financial assets totaling near $49 trillion, which equals more than half of global GDP.

How can public banking and financial institutions continue to thrive in the apparently hyper-capitalist environment of most countries? Two factors are pivotal. The first one has to do with the recent decades of financial crises, which have led to the growth of these public institutions to rescue finance, if not the economy as a whole. The second may be a bit more surprising: in some ways, these institutions are actually more efficient and safer than private financial institutions.

Despite mainstream economics’ claim to the contrary, there are some competitive advantages of these public institutions that allow them a fighting chance, even in the capitalist marketplace. They are the following:

Public banking and finance institutions tend to emphasize “relationship” banking so that bankers and customers get to know each other well; this increases knowledge of credit risks and enhances trust, thereby reducing manipulative or fraudulent behavior on both sides.

Public mandates and lack of shareholder control typically lead public banking and finance institutions to adopt less risky behavior than their private counterparts. This can result in less instability.

Access to capital at lower cost: Many public banking and finance institutions have lower costs for capital because they are perceived as being safer than private banks that engage in high-risk activities. They tend to build capital through profit retention, since they are not under pressure to distribute dividends to shareholders, and they do not face the same shareholder demands for rapid expansion.

Public mandates lead to banks passing on advantages to customers: Public banking and finance institutions pass on lower expenses to customers rather than needing to pay extraordinarily high executive salaries and large amounts of dividends. This attracts more borrowers and more depositors and lenders.

Economies of scale: Even though relationship banking and tight monitoring of credit risks can be very costly, public banking and finance institutions can achieve economies of scale by joining networks that provide services like underwriting, technical assistance, and help identifying lenders and good borrowers. Such networks can at least partially erode some of the advantageous economies of scale that large private firms have.

The lack of alternatives to Wall Street banks gave rise to the Public Bank LA initiative, which began a campaign to establish a municipal bank that would be owned by the city of Los Angeles.

Still, this kind of banking seems stunted in the U.S. relative to some other places in the world, but I would argue that this is because private banking gets massive subsidies from the U.S. government (including the Federal Reserve) that mostly are not available to public banking and finance institutions. It will take political mobilization to change this, and, thankfully, that mobilization is beginning to happen.

What kind of grassroot initiatives are currently going on in the fight for public banking?

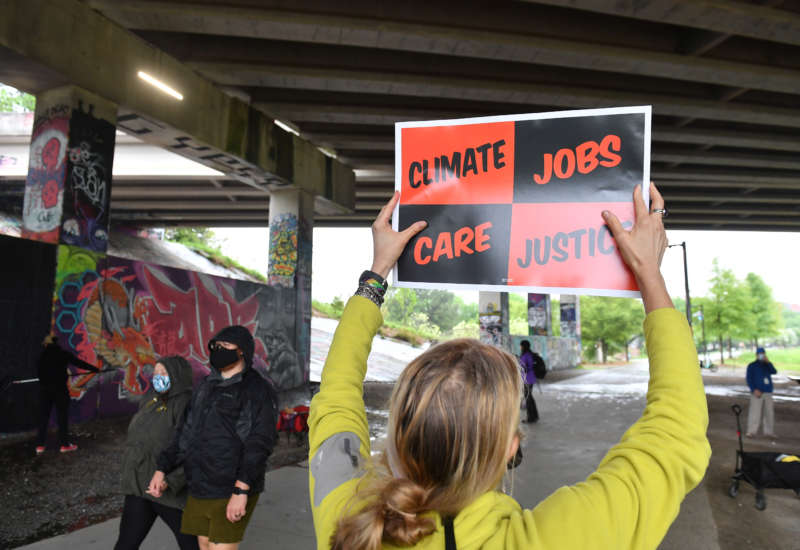

Public banking initiatives in the U.S. have gained unprecedented momentum in recent years. The origins of the resurgence of interest in public banking go back to the Occupy Movement, which emerged in 2011 as a response to the economic and social injustices heightened by the global financial crisis. The infrastructure crisis, the exclusion of millions of Americans from basic banking services and private banking’s longstanding history of financing environmentally harmful projects have further fueled interest in public banking across the U.S.

As a response to these problems, public banking advocates have started state and local initiatives to establish public banking institutions in a number of localities. Alongside these initiatives, networks of organizations and advocacy groups have been created. The Public Banking Institute, the California Public Banking Alliance and the National Public Banking Alliance are among the major think tanks and organizations advocating for public banking. These organizations have forged connections with a panoply of nongovernmental organizations and grassroots movements to help develop existing coalitions and mobilize support.

Advocates working toward establishing public banks follow two common approaches. The first approach is to establish public banks at the city, county or regional level. In most cases, the state governments need to pass legislation to authorize the creation of local-level public banks. The second approach involves establishing a state public bank, like the Bank of North Dakota, which would act as the public depository for state funds and partner with local lenders.

There are attempts in different states to establish public banks following both of these approaches. These efforts are spread throughout the country. Here is a brief rundown.

New York State and Pennsylvania host initiatives to establish public banks at local and state levels. Both states are working toward passing a bill that would provide the legal background for local governments to establish their own public banks. In Pennsylvania, this legislation will be used to establish a city public bank in Philadelphia. Besides, both states are pursuing legislation to establish state-level public banks. The advocates in Pennsylvania are working closely with the Public Banking Institute to establish a public bank following the Bank of North Dakota model. These efforts are supported by numerous grassroots groups in both states.

Washington State is another important hub for public banking advocacy. Over the past several years, advocates have been pushing to establish a state-level public bank that would function as a public depository for state money and would be authorized to manage and invest state funds in infrastructure development programs. Although these efforts have been facing fierce ideological opposition, particularly from the state treasurer, the organizers who participated in our survey expressed their commitment to continue pushing for public banking in the coming years. Besides these three states, there are efforts to establish state-level public banks in nine other states: Colorado, California, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon and Virginia.

The Public Banking Act, a federal bill introduced to Congress in October 2020 aims to enable and encourage the creation of public banks at state and local levels.

The most significant victory for the public banking movement took place in California in 2019 as the legislation enabling the creation of local public banks, AB 857, passed. This is the first municipal banking legislation in the country authorizing the state to charter 10 municipal banks over seven years. There are also ongoing efforts to convert California’s Infrastructure and Development Bank (the IBank), currently an infrastructure loan fund, into a state-level public bank.

The lack of alternatives to Wall Street banks gave rise to the Public Bank LA initiative, which began a campaign to establish a municipal bank that would be owned by the city of Los Angeles and would manage city funds in the public interest.

One of the first major accomplishments of Public Bank LA was to facilitate a city referendum to form a public bank. Although the referendum fell short at 44.15 percent support, this momentum was translated into the formation of the California Public Banking Alliance, which is a coalition of 10 public banking grassroots groups across the state.

Besides local public banking, advocates in California have been campaigning for a state-level public bank. These efforts started in 2019 with the introduction of a bill, SB 528, by Democratic Sen. Ben Hueso. This bill aimed to transform the IBank into a depository institution that could take deposits from cities and countries, manage them and provide loan guarantees and conduit bonds to California projects. After the failure of this bill, a new task force started working on converting the IBank into a state-level public bank. In July 2020, a new bill, AB 310, was introduced for this purpose. AB 310 has two main components/targets: (1) expanding the IBank’s lending capacity; and (2) converting the IBank into a state public bank. The expansion in the lending capacity was introduced to support local governments and small businesses, targeting especially those owned by disadvantaged groups.

Overall, California can be considered as a center of public banking advocacy work in the U.S. There is a large and growing public support for public banking, and the advocates have been successful in building coalitions, forming organizations and introducing legislation. By following these developments and building dialogue, advocates in other parts of the country can take important lessons from the victories and challenges faced by public banking organizers from California.

Still, without broader federal support, such as what the government gives private banks, these public banks will always be at … somewhat of a disadvantage. Thankfully, a number of progressive legislators and activists are pursuing initiatives at the federal level to support public banking and finance institutions and activities.

Bill H.R. 8721 was introduced in October 2020 to provide for the federal charter of certain public banks. What would be the role of a public bank created by the federal government? Could it provide an effective pathway toward financing the green transition?

Some have proposed the creation of a federal infrastructure bank — this bank could be restricted to funding only climate-friendly investments.

The Public Banking Act, a federal bill introduced to Congress in October 2020 by Representatives Rashida Tlaib and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, speaks directly to some of the demands expressed by public banking advocates in our survey analysis. The Public Banking Act aims to enable and encourage the creation of public banks at state and local levels by establishing a comprehensive federal regulatory framework, grant programs and support [for] the financial infrastructure. In other words, this bill encourages the creation of public banks by providing “top-down” support for “bottom-up” local initiatives.

Under the Public Banking Act, public banks can become members of the Fed. In addition, this legislation presents a pathway for state-chartered banks to gain federal recognition and identifies a framework for public banks to interact with postal banking (where the USPS serves as a bank), or FedAccounts (where everyone gets an account with the Fed through which they could receive direct payments, such as stimulus checks, from the government). The bill also introduces lending rules and regulations regarding excluded and marginalized groups, ecological sustainability and data reporting. For instance, it prohibits public banks from engaging in or supporting fossil fuel investment. Besides, it directs the Fed to develop regulations and provide guidance to ensure that public banks’ activities remain consistent with climate goals and are universal and comprehensively include historically excluded and marginalized groups.

A key feature of the Public Banking Act is that it recognizes the need for more federal-level support for local- and state-level public banking initiatives. This legislation also shows that the Fed and the Treasury can be instrumental in supporting the financial infrastructure outside of their typical models of action.

There are other possible federal initiatives to help finance a Green New Deal. The Federal Reserve itself could buy green bonds, as suggested, for example, by Robert Pollin. Or the government could create a free-standing “Green Bank” at the federal level to mobilize private capital and combine it with public monies to help fund the green transition. Finally, some have proposed the creation of a federal infrastructure bank, and presumably, this bank could be restricted to funding only climate-friendly investments. All of this could greatly complement initiatives at the state and municipal levels to promote solutions to the climate emergency.