The language of “American racial reckoning” has been frequently cited since the tragic murder of George Floyd and the raising of American consciousness regarding its history of systemic racism. The ongoing murders of Black people by the police, and the profound ways in which Black people must continue to struggle against forms of anti-Black inequity across various political, social and economic indices, prove that there needs to be a robust reckoning. And yet, these realities perpetuate forms of anti-Black pain and suffering that thwart and belie such reckoning.

To remind us of what is at stake, and to exhume the pain and suffering that much of the U.S. would rather not see, I spoke with The Very Reverend Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas, who reveals the anti-Black narrative that constitutes the core of this country and how that narrative is fundamentally linked to this country’s collective psyche. Douglas also delineates how anti-Black theories and beliefs — even the force of white Western Christian traditional practices — have marked the Black body as “evil” and thereby eliminable. Additionally, Douglas examines how anti-Blackness impacts the lives of Black women in specific hetero-patriarchic forms and their subjugation to carceral policing. She does this while courageously maintaining a powerful form of faith that shapes how she remains focused on a future that promises the recognition of each person’s sacred humanity.

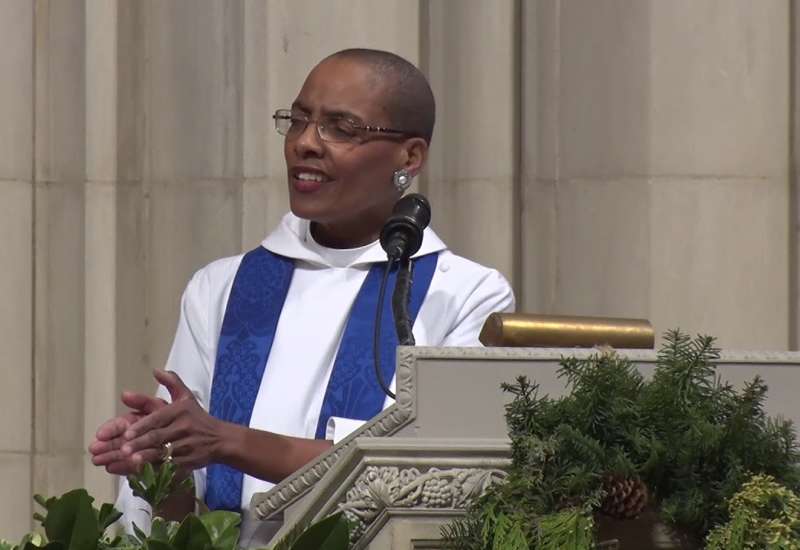

Douglas serves as the Dean of the Episcopal Divinity School and the Bill and Judith Moyers Chair in Theology at Union Theological Seminary. She also serves as the Canon Theologian at the Washington National Cathedral and Theologian in Residence at Trinity Church Wall Street. She is the author of many articles and books, including Sexuality and the Black Church: A Womanist Perspective and Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God, and the forthcoming Resurrection Hope: A Future Where Black Lives Matter (Orbis Books).

George Yancy: You’ve talked about how you started to ask at the early age of 6 why it is that we as Black people are treated so badly. The question brings to mind the arc of our deep existential suffering from enslavement, Black codes, the collapse of Reconstruction, Jim and Jane Crowism, the criminalization and lynching of Black bodies etc. Within this historical arc, I’m also referring to Emmett Till, who was tragically and brutally murdered in 1955, and the four young Black girls (Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson and Denise McNair) who were murdered at the 16th Street Baptist Church, which was bombed by white supremacists in 1963. In our contemporary moment, I’m also thinking about the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and 20-year-old Daunte Wright, who was recently killed by a white police officer, in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota. Also, relevant here is what happened to Afro-Latino Caron Nazario, a Second Lieutenant of the U.S. Army Medical Corps, who was recently held at gunpoint and pepper-sprayed by Virginia cops as he remained calm in his parked vehicle. I’m also thinking about new forms of Jim and Jane Crow, including the violence of the foster care system in relation to Black mothers, and the prison-industrial complex in terms of how Black women’s incarceration specifically negatively impacts the mother-child bond, the disproportionate incarceration of Black bodies, more generally, and so on. So, what is it? Why are Black people treated so badly?

Kelly Brown Douglas: With the seemingly unrelenting attacks on Black bodies, I have become increasingly aware that the dehumanizing and deadly treatment of Black people in this country goes beyond the white supremacist foundation upon which this country was built. The almost taken-for-granted violence of white supremacy that is endemic to this nation is manifest in the systemic, structural, and cultural ways it privileges whiteness and penalizes those who are not raced white.

However, such privileges and penalties do not adequately account for the visceral assaults, sometimes fatal, upon Black bodies, as in the case of a Tony McDade, Atatiana Jefferson, or Casey Goodson Jr., and this list, horrifically, could go on and on. These consistent, malicious attacks, while grounded in whiteness, reflect more than a belief in the superiority of whiteness. Such attacks bespeak a singular, deep-seated fear, if not contempt, for Blackness itself. It is only in appreciating the pervasive and distinctive presence and dehumanizing presuppositions of an anti-Black narrative ensconced within this country’s collective psyche, that we can begin to understand the intensity of white repulsion when it comes to Black bodies.

Now, it is important to recognize that anti-Black beliefs, if not theories, are deeply rooted within the Western philosophical and even Christian tradition. For instance, in his attempts to understand the diversity of human creation, Aristotle laid a philosophical foundation for an anti-Black narrative that rendered Black people as inferior and wanton beings. In so doing, he fostered the notion that Blackness signaled an immoral, if not dangerous, nature. That Blackness has been seen as a signifier for sin replete with images of the devil as Black, as exemplified throughout the Christian tradition, is one exemplar of how Christianity has provided a sacred foundation for an anti-Black narrative.

The point of the matter is: These philosophical and theological beliefs served as a precursor to what would become a well-formed anti-Black narrative.

Within the anti-Black narrative, Black people are seen as dangerously threatening. Like animals, Black people are viewed as likely to erupt into a life-threatening tirade with little provocation, and thus are considered inherently violent and to be feared. An anti-Black narrative undoubtedly arrived in America with the earliest settlers dispatched from England in 1607 to form what became known as the Jamestown Colony in Virginia.

Fast forwarding, “The Make America Great Again” vision promoted by Donald Trump brought to the surface the nation’s fundamental white supremacist values as defined by an anti-Black narrative. In so doing, Trump’s pledge to “Make America Great Again” (read, white again) played upon the fears about Black people as hyper-dangerous threats to white civilized America, thus provoking in white America an almost reflexive response to protect “whiteness” against the “perceived” threat of Blackness at all cost.

This could be readily seen in incidents that seemed to multiply across the country where police were called on Black people simply going about the business of being human — such quotidian activities as Black people waiting, barbecuing or birdwatching. Even worse, was when the presence of a Black body almost instinctively elicited deadly force from police, as was the case in relation to Elijah McClain, George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

That which keeps me grounded and gives me hope is the very Black faith that was handed down to me through my grandmothers, who had received that gift of faith from their grandmothers.

Moreover, the fact that Black people are disproportionately trapped in poverty — with its social co-morbidities of inadequate health care, substandard housing, and insufficient employment, educational and recreational opportunities — is the result of an uninterrupted anti-Black narrative. There is no getting around it: An anti-Black narrative is pervasive within America’s social-cultural mindset and soil. It is for this reason that Black people are treated so badly.

Thank you for saying their names, for identifying such persons by name. That act alone helps us to remember them, to recognize that they were here, that they were human beings who were subjected to what you powerfully call an anti-Black narrative. In the light of so much anti-Black racism, how do you conceptualize yourself as a Black female Christian? In other words, who are you called to be amid such anti-Blackness?

First of all, as a person of faith, I am accountable not to the unjust ways of the present, but to the just future to which God calls us. And so, in the least, I am called to speak out and stand against that which does not reflect God’s just future. This is a future where all persons are treated as the sacred creations that they are. Put simply, I must speak out against any policies, systems, structures and ideologies of beliefs that negate the sacred humanity of persons because of how they are raced, gendered, sexually oriented, or because of the language they speak, country they come from, labor they perform, and any other discriminating human construct. Moreover, I must witness for that just future, which means working to create spaces and indeed a society where all persons have equitable opportunity to flourish and thrive into the fullness of their sacred humanity.

Second, as a Black female I am accountable to those Black people, especially those Black women who came before me. I think oftentimes of those Black persons who endured the realities of anti-Blackness that was chattel slavery. These were people who never breathed a free breath, never dreamed that they would breathe a freed breath, but fought for freedom anyhow. They fought for a freedom they knew they would never see, yet one they believed would one day become a reality. The freedom in which they put their faith is the very freedom that is the justice of God. It is because of their fight and belief that I as a Black female have the freedoms that I enjoy, as fraught and contested as they may sometimes be given the constructs of white supremacist hetero-patriarchal oppression. And so I am called by their struggle of faith, to continue the fight for a freedom that I may never see, but one that perhaps my children and their children will experience. This is a freedom from anti-Blackness. It is the freedom to live in a nation, indeed a world, where all Black lives matter.

I hear in your response the act of giving thanks to those who have come before you, those Black people who clung to a future that wasn’t certain and yet they endured. I too am thankful and indebted to them. I am often troubled, though, by the lack of national attention that is given to Black women who are subjected to police brutality, especially as compared to the national spotlight that is placed upon Black male bodies that are subjected to deeply problematic policing. Indeed, Black women and women of color (including, of course, trans women of color) undergo experiences of pain and suffering that we should not conflate with the suffering of Black men or men of color. And while this isn’t about “oppression Olympics,” I do think that it is important that Black women’s pain and suffering under sexism, patriarchy and racism, are marked and rendered visible lest we find ourselves guilty of multiple forms of erasing Black women’s lived complexity. Given the importance of your work within the area of Black womanist theology, can you describe how it helps to frame more accurately and insightfully the historical and the lived or phenomenologically complex dimensions of Black women?

Yes, you are right. Black women’s pain and suffering has become virtually invisible within the wider social discourse, protest movements and collective social consciousness. As scholar Michele Bratcher Goodwin has explained, during this time of focus on racialized police brutality, the injustice perpetrated against Black women has played “off mainstage, relegated to the corner of another theater.” Yet Black women are no less victimized by the ravages of systemic racism when it comes to policing and the criminal justice system. Black women are “caught within the clutches of a broken or intentional criminal justice system,” even as they are continually “ignor[ed] as victims.”

For instance, according to the Sentencing Project, “In 2019, the imprisonment rate for African American women … was over 1.7 times the rate of imprisonment for white women.” Moreover, “African American girls are more than three times as likely as their white peers to be incarcerated.” This data as well as the fact Black women’s oppression has been virtually ignored evince what Pauli Murray identified as Jane Crow, which is the intersecting realities of raced and gendered oppression. More specifically, the anti-Black narrative has historically been shaped not only by color but also gender.

As is well documented, Black women became the perfect foils to white women. While white women were considered virginal, pure angels in need of protection, Black women were considered wanton, lascivious Jezebels in need of controlling. Black women were essentially entrapped within the catch-22 of a violent “intersection.” For inasmuch as they did not meet the white female standard of beauty, they were not regarded as “ladies” to be respected; the more that their Black skin marked them for a way of living that defied ideal “womanhood,” then more “validity” was given to the meaning of their Black body aesthetic. Their Blackness signified that they were in fact not proper women, they were not “Victorian ladies,” even as it ensured that they would never enjoy the privilege of being treated as a Victorian lady, and worse yet it ensured brutal assaults against their bodies. Most particularly, it enabled white men to literally rape Black women with moral and legal impunity. In the logic of the anti-Black narrative, a Black woman could never be raped since she was an unabashed temptress and thus responsible for any such assault against her body.

Essentially, what we recognize are the realities of raced and gendered oppression that have intersected on Black women’s bodies. It is because of these intersecting realities of oppression that 19th century “Negro Club Woman” Anna Julia Cooper proclaimed, “Only the BLACK WOMAN can say ‘when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.’” For it is the case, that if Black women are to live into the fullness of their humanity, then the aggregate complex of white supremacist heteropatriarchy would have to be dismantled. With this being the case, then those who are oppressed by any aspect of this oppressive complex would themselves be free. It is perhaps for this reason, that there have been no people more instrumental in keeping America’s democratic vision alive than Black women.

It is indeed those persons who have been on the utter underside of justice — who have experienced the penalties of injustice — that are the best barometers for justice. Otherwise, justice is too easily confused with gaining privilege in an unjust system. This has been the case historically, as most clearly evident in the 19th-century struggle to expand the right to vote. On the one hand, white women have fought to eliminate gender requirements while on the other hand Black men fought to eliminate racial requirements and thus gain the patriarchal privilege to vote. Neither took into account that without the elimination of both racial and gendered restrictions, Black women would still be disenfranchised.

What we most clearly see here is the sovereign value attached to “whiteness” and “maleness.” So, for instance, to be both white and male affords one the highest level of political, social, economic and even ecclesiastical privilege. To be white and female eliminates the claim to gender privilege, but preserves the right to race privilege (hence white women have fought for the race privilege granted white males). To be Black and male portends a “raced” male privilege, thus affording them privileges over Black, but not white, women. And so it is that historically Black men have fought to eliminate the restrictions of race. Yet to be Black and female — let alone if one is trans, gender non-conforming or queer — is to have virtually no claim to the privileges accorded in a White hetero-patriarchal society.

The bottom line is that Black women as a group are characteristically relegated to the absolute margins of political, social, economic and ecclesiastical privilege and discourse. Yet, this marginality has not signified lack of agency as implied in Cooper’s pronouncement. Clearly, Cooper recognized that Black women possess a unique perspective on the complicated, intersecting realities of injustice in this country that has made them uniquely qualified to chart the course for not just Black freedom, but a freedom from the tyranny that is white supremacist heteropatriarchy.

So, it is no wonder that Black women have been — and continue to be — in the forefront in moving our nation to live into its better angels, including in the fights for equal rights and voting rights. And that, again, is because Black women continue to bear the full weight of the intersecting realities of white supremacist, hetero-patriarchal realities of injustice. In this regard, what Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist of the 1619 Project Nikole Hannah-Jones says of Black people in general applies most especially to Black women. She says, “Our founding ideals of liberty and equality were false when they were written. Black Americans fought to make them true. Without this struggle, America would have no democracy at all.”

I was recently discussing Black sexuality with my undergraduates in one of my philosophy seminars and the issue of Black female sexuality was raised. We explored the horrible, caricatured, and racist cartography of the Black female as defined as “Mammy,” “Jezebel,” and “Sapphire.” Each of these stereotypes is framed according to a distorted understanding of Black women’s sexuality. Of course, Black men have also been subjected to harmful racist images. Think here of the “Black Buck.” Through the lens of white supremacy, Black people have been reduced to their bodies; they are depicted as base, subhuman, hypersexual and hyper-sensual creatures without reason. How is this distorted image of the Black body related to a white theology and perhaps even Western philosophical assumptions about the body, more generally?

Yes, this indeed is the case as I have alluded to in my previous responses. But let me summarize how this has been the case when it comes to Christianity and the white theological tradition. There is no doubt that the Western Christian tradition has influenced if not provided a sacred canopy for white supremacists/anti-Black beliefs and attacks upon Black bodies, as well as justification for the social subjugation of Black people. Essentially, the Western Christian tradition opened wide the door for the possibility of utilizing sexuality as a means of devaluing and demonizing human beings. This theological perspective of the body came to prevail within the Christian tradition. Specifically, the body was seen as a cauldron of sinful passions, such as sexual lust. Simply put, this theological tradition asserts that sexuality is a cauldron of evil and is an obstacle to one’s salvation if not a threat to one’s very humanity.

By maintaining the evilness of sexuality, Christianity provided a theological basis for any claims that people who were deemed to be governed by sexual desires are innately evil and need to be controlled. It is in this way that Christianity has perpetuated a theological tradition that is compatible with a white supremacist, anti-Black narrative. For we are reminded that this is a narrative which regards Black people as hyper-sexual and thus dangerous. Hence, Christianity is, in the least, complicit in sustaining white attacks against the Black body. For again, inasmuch as sexuality is considered evil, so too are “hyper-sexualized” Black people. Therefore, if Black people are considered evil by nature, then to protect society from them, even if it means their death, is seen as reasonable.

To sum up here, there is a prevailing Christian theological tradition that not only sanctions Black people’s dehumanization, but also suggests their demise. This theological tradition is most prominent within fundamentalist versions of Christianity that maintain a more literal approach to the Bible. It is perhaps no coincidence, therefore, that evangelical Protestantism prevails in the South where most Black lynching historically has taken place.

Those are rich theological insights vis-à-vis anti-Black racism, especially in terms of the Black imago in the white imaginary. When I think about the term “redemption,” I think about the process of freeing, of being extricated from captivity. So many human beings are suffering, and that suffering is unbearable. The Earth itself seems to cry out for redemption. The Black body continues to be held captive, fungible and disposable in relationship to anti-Black forces. We bear witness to our Asian brothers and sisters undergoing violence because of poisonous anti-Asian xenophobia; we grapple with those who are our neighbors that are excluded as they flee poverty and violence within their own countries; we are aware of human trafficking and labor abuses worldwide; we bear witness to femicide in Latin America and around the world. Climate change and the threat of nuclear weapons pose a heightened existential threat to life on earth. Given the wreckage that we have created, it is hard for me to believe that we will be redeemed. There are times when I wonder if we are in fact irredeemable. What is it that keeps you grounded in the face of so much dread? Does womanist theology play a role? Is there an eschatological hope that you possess? Given the gravitas that we collectively face, share your wisdom.

Actually, the answer is easy for me. That which keeps me grounded and gives me hope is the very Black faith that was handed down to me through my grandmothers, who had received that gift of faith from their grandmothers. You see, Black faith finds its meaning in the very absurdities and contradictions of Black life. For, Black faith was not born during a time when Black people were even nominally free. And perhaps that’s the strength of Black faith itself — an empowering power in times of absurdity. Somehow Black people were able to affirm their faith in the justice of God, and thus in God’s promise in a more just future, even in the middle of the evil that was chattel slavery. It was this faith that gave them the “courage,” the determination, to fight for freedom, to fight for Black life in the midst of a society that denied Black freedom and destroyed Black lives.

As I said earlier, it is because of their faith in the freedom and promise of God that I can be here engaging in this conversation and doing the work that I do. And so, for me to give up on our society, for me to give up on our world, for me to despair, is for me to betray the faith of all of those grandmothers who kept the faith and kept fighting for justice and freedom. The way I see it is, if they could keep hoping and believing when there was certainly no reason to hope, then I have no excuse to not continue to fight for that in which they hoped — a more just future for their children and their children’s children.