A bill aimed at exposing deep-pocketed dark money political donors and increasing campaign transparency failed in the Senate on Thursday after zero Republicans voted for the bill, allowing billionaires and special interest groups to continue to exercise huge influence over elections with little accountability.

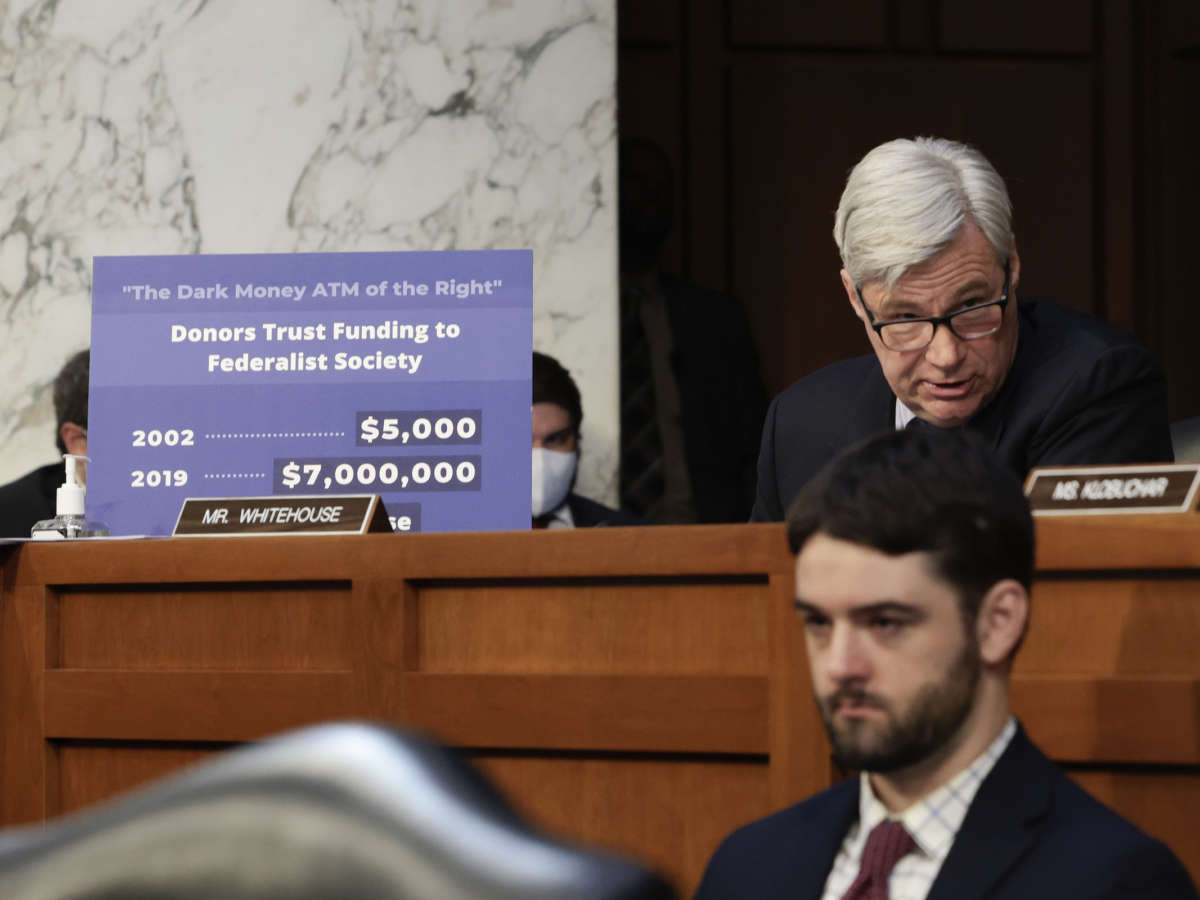

The DISCLOSE Act, introduced by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-Rhode Island), failed 49 to 49, falling short of the 60-vote threshold to advance the bill. Nearly every Republican in the Senate, except for one who didn’t cast a vote, voted against the legislation that campaign transparency advocates and government watchdogs say is crucial to combating the flood of cash from wealthy dark money donors that was unleashed by Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (FEC) 12 years ago.

Endorsed by President Joe Biden, the DISCLOSE Act requires dark money groups — trade associations, shell corporations that give to Super PACs, tax exempt so-called “social welfare” groups, and more — to disclose donors who give $10,000 or more during an election cycle. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Koch Industries are some of the largest dark money groups in politics today.

Democrats lamented the failure of the bill, saying that it exposes Republicans’ motivation to keep the flow of dark money running.

“Today, Senate Republicans stood in lockstep with their megadonors and secretive special interests to protect the most corrupting force in American politics — dark money,” Whitehouse said in a statement after the vote. “The American people are fed up with dark money influence campaigns that rig their government against them and stymie their priorities.”

Various versions of the DISCLOSE Act have been introduced since Citizens United was handed down in 2010. It has been blocked by Republicans many times, even as they conveniently complain about dark money when liberals benefit from it.

Government watchdogs say that passing the bill would be an important step toward combating billionaires’ and corporations’ influence in politics.

Thanks to Citizens United, corporations and billionaires can give unlimited amounts of money to influence elections, while giving to dark money groups allows them to stay anonymous. The decision unleashed a barrage of dark money into politics; an analysis earlier this year found that billionaires are spending nearly $1 billion more per election cycle than they were before the decision. Their influence is so large that, as of this summer, nearly half of the funding — $89.4 million — raised by Republicans’ two largest super PACs at that point in the 2022 election cycle came from just 27 billionaires.

The DISCLOSE Act wouldn’t put restrictions on large donations — which advocates say is also needed — but would rather increase transparency around them. This could discourage donors from giving in large amounts and would give the public a better idea of who is pulling the levers in U.S. politics. Proposals to tighten campaign transparency laws are also widely popular among the public.

A recent example of a major dark money political donation was that of Barre Seid, who gave over $1.6 billion to a little-known dark money group headed by Leonard Leo, who was instrumental in nominating every right-wing Supreme Court justice who sits on the bench today.

This is likely one of the largest single political donations ever made — and it was entirely legal thanks to Citizens United. It’s likely the donation was only made public because of a tip to journalists about the donation.

Biden cited that donation in a speech calling for the passage of the DISCLOSE Act on Tuesday. “Dark money has become so common in our politics, I believe sunlight is the best disinfectant. And I acknowledge it’s an issue for both parties,” he said. “But here’s the key difference: Democrats in the Congress support more openness and accountability. Republicans in Congress so far don’t.”