In early 2021, NFTs blew up, adding, alongside COVID-19, another viral acronym to the global vocabulary. Like the coronavirus, we knew a great deal about the new phenomenon before we knew how it worked. Still, it was easy to work out that the primary operating principle of so-called non-fungible tokens, widely if incorrectly equated with digital art, seemed to be money. Every day there were new headlines of people paying more money than you’ll ever earn for something you’ll probably never understand. But such is the nature of the art market, and besides, we hadn’t yet learned the real cost of NFTs.

A reckoning came on the heels of the initial hype, with outlets like Wired declaring, ‘NFTs Are Hot. So Is Their Effect on the Earth’s Climate.’ The Verge tied NFTs to a ‘climate controversy’, while one group of academics creatively calculated that “the mining devices verifying NFT sales in one month in 2021 would be responsible for approximately 18 unnecessary future deaths from carbon emissions.” Suddenly, NFTs went from absurd to murderous. Also, people finally paid attention to the mining devices.

What is an NFT, Anyway?

An NFT in and of itself does not kill people or bring ruin to ecosystems. In fact, for most of its life, an NFT sits idle like a property deed in a land registry, carbon neutral as a rock. And that’s all it is, really: a deed which proves the ownership and authenticity of a particular asset, whether a house, a painting, or the first tweet. NFTs are registered on the blockchain, an immutable public record that lends the token its non-fungibility. You own this, declares the blockchain, everyone look!

Of course, there’s no good reason to show off the papers to your house. But what about, say, the certificate of authenticity to your Mondrian? In 2021, the public bragging rights granted by NFTs converged with the cultucurious economics of art in general and the infinity of digital art in particular. Liberated from the shackles of time, space, and talent, anyone could produce a work of digital art, tokenise it, and let hype take it from there. Cryptoart flooded the market, producing a dizzying torrent of numbers. At one point, tens of millions of NFTs were sold every day which, at their peak, were worth more than $40 billion USD.

Big Hype, Bigger Climate Damage

This frenzy left a monumental carbon footprint. That’s because every action in the lifecycle of an NFT uses energy. When an NFT is created, the world dies a little. So too every time an NFT is bid on, sold, or transferred. Since NFTs can be traded forever, there is technically no end to its carbon-emitting lifecycle. What’s really shocking is just how much energy these actions require. From creation to sale, the average cryptoart NFT has a footprint of around 340 kWh, 211 KgCO2 – more than the flight of a single passenger from Berlin to Tel Aviv. In one infamous example, a single artist’s NFTs collection produced as big a footprint in six months as a person would over 77 years of using electricity. That’s the equivalent of boiling a kettle 3.5 million times (here’s a fantastic breakdown of these tragic figures).

The Problem With Proof-of-Work

The problem lies in the way some blockchains verify an action like creating or transferring an NFT. On Ethereum, where about 80% of NFT trades take place, this is called proof-of-work (Bitcoin also uses this method). With proof-of-work, computers compete to solve complex cryptographic puzzles in a process known as “mining.” Once the puzzle is solved, the action is approved. It’s an ingeniously inefficient design. As one engineer explained, “If it’s stupendously compute-heavy and difficult to write to the blockchain, then it can’t be done frequently enough to pose a security threat.” Worse still, the puzzles become exponentially difficult to solve, requiring ever more computing power and creating a spiralling excess of energy consumption. A person used to be able to mine from their laptop. Now, this happens by networks of machines in warehouses the size of a Walmart.

The thing is, the cost of electricity to mine most NFTs is higher than the price you can sell them for. So why spend all this energy on securing something that’s essentially worthless? As the artist Everest Pipkin writes, “During unprecedented temperature increases, sea level rise, the total loss of permanent sea ice, widespread species extinction, countless severe weather events, and all the other hallmarks of total climate collapse, this kind of gleeful wastefulness is, and I am not being hyperbolic, a crime against humanity.”

Cleaner NFTs are Possible

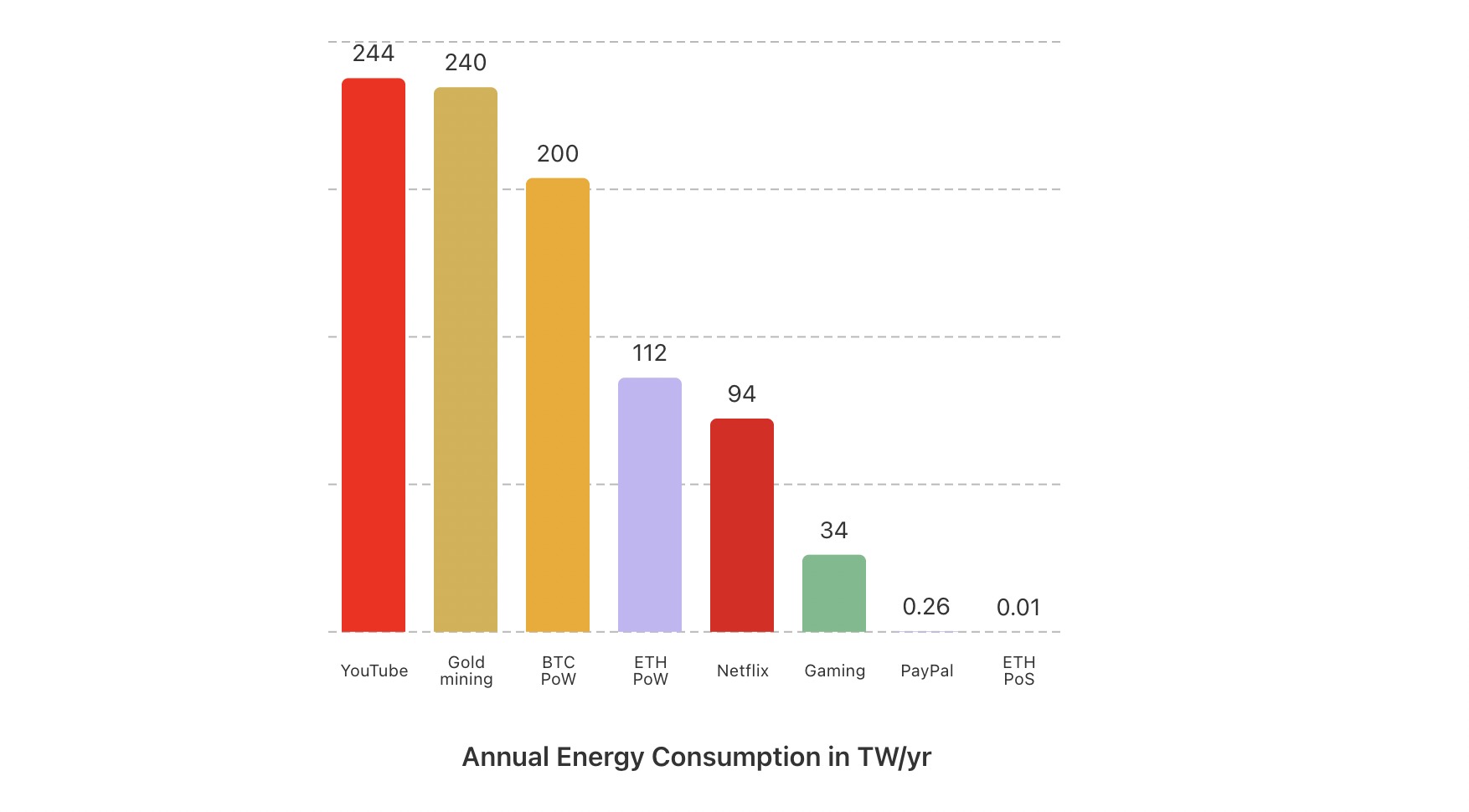

The good news is there’s an alternative to the mining model. Called proof-of-stake, it relies on crypto owners to use their coins as collateral for the right to verify transactions on the blockchain, which earns them more coins. This risk and reward mechanism is intended to incentivise the good policing of blockchain activity as behaving nefariously would be expensive and ostracising. Most importantly, proof-of-stake uses around 99% less energy than proof-of-work. When the nature program WildEarth released a collection of animal NFTs to raise money for conservation, it used the proof-of-stake Polygon blockchain. Still, many are sceptical of giving NFTs a green label. Earlier this year, WWF was backlashed into ending its sale of “non-fungible animals” after less than 48 hours. The animal NFTs also used the Polygon blockchain, which critics noted runs partly on Ethereum. According to one digital currency economist, a single transaction on Polygon is 2,100 times higher than what WWF claimed.

Beyond NFTs: Greener Blockchains for Genuine Sustainability

With NFT transactions culpable for carbon-related deaths, social pressure has spurred the art market to ditch deliberately polluting proof-of-work blockchains for more eco-friendly consensus protocols like Cardano and Solana. Ethereum, too, is cleaning up its act. On September 15, the second-most popular blockchain after Bitcoin switched to proof-of-stake. That means the more than one million transactions that happen on Ethereum every day are now around 2000 times more energy efficient than before. This is a promising development not only for NFTs but also every existing as well as future application running on Ethereum. One such example is DIBIChain, which aims to help companies trace the environmental impact of their products and processes from beginning to end. Now, every piece of information recorded on the blockchain will be much cleaner than before. From water management to energy distribution, organisations can finally use blockchain technology to make processes genuinely sustainable without being accused of greenwashing.

The ecological damage caused by the first NFT wave can’t be reversed but ideally it only happens once. A great thing about new technologies is that they’re nimble. Once the energy problem became clear, blockchain developers moved quickly toward a solution. If only our policymakers could do the same when it comes to making the switch to renewables. After all, the energy transition can also help make less adaptable blockchains like Bitcoin more eco-friendly. With an energy budget nearly equal to the entire country of Argentina, Bitcoin mining would do well to run on wind and solar. Meanwhile, in the case of NFTs, issuers, marketplaces, and buyers will need to be diligent about the technology at the heart of their actions – especially now that there’s no excuse not to go green.

The post NFTs: The Hype, the Climate Cost, and a Greener Future appeared first on Digital for Good | RESET.ORG.